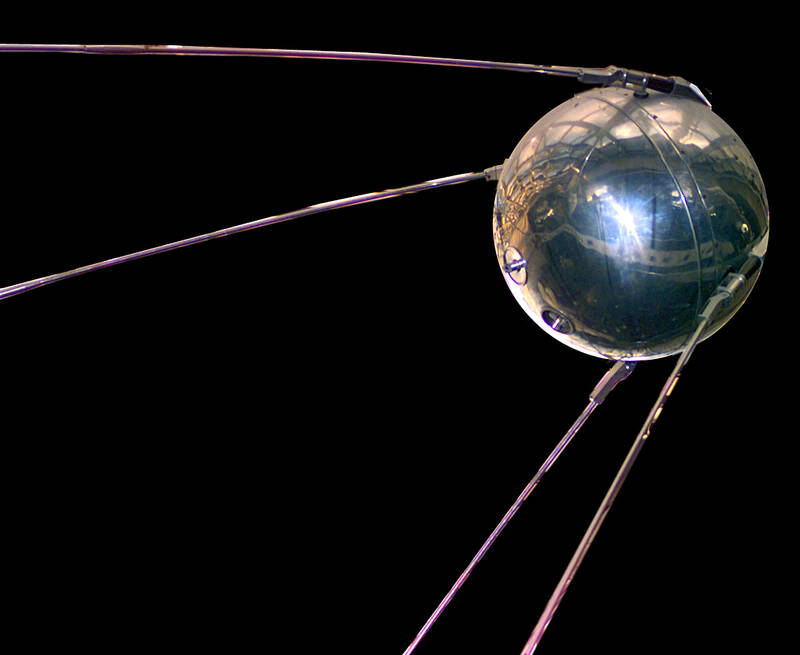

One of the most transformative technical achievements in human history took place on Oct. 4, 1957, when the Soviet Union launched the satellite Sputnik 1 into orbit. Americans, utterly convinced of their technical and industrial superiority at the time were shocked, though some tried to play it down by dubbing it the “beeping grapefruit” due to its size and sole capability.

That jibe was entirely unfair, as it was a proof-of-concept mission. That they were able to achieve the historic first of launching into space and accurately position a satellite to orbit the earth was a singular achievement. The beeping radio waves ensured they could both prove and track their success.

Two months later, the American launch of Vanguard failed spectacularly.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Many Americans did take Sputnik very seriously at the time, and the term “Sputnik moment” today means an existential wake-up call. Those that took it seriously were proven correct; in less than four years the Soviets went from a “beeping grapefruit” to sending the incredibly brave Yuri Gagarin into space and safely returning, a first for humanity.

Note the positive language I used in describing the Soviet achievements. It is not to praise the Soviet Union, one of the most murderous regimes in history, but the talented people who accomplished these goals. This distinction is relevant in a Chinese context today.

SOVIET DOWNFALL

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

When DeepSeek Artificial Intelligence (AI) was launched in January, it was laughably dubbed a “Sputnik moment.” It was not even close. It was not a revolutionary leap into the unknown but rather an evolutionary improvement on the AI offerings already available.

Still, it was impressive and a wake-up call to the American tech giants that the Chinese were competitive. A string of recent AI releases by a range of Chinese tech giants proved that DeepSeek was not alone, but part of a Chinese ecosystem capable of challenging the Americans on most benchmarks, and often for far cheaper. The notoriously arrogant American tech companies were served warning they could not be complacent.

The Soviet Union proved that by diverting resources and cultivating exceptional talent, great achievements could be accomplished, but only to a point. Their top-down rigid setting of priorities lacked the nimble flexibility of the American system.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Consumer electronics is a perfect example. The US also diverted resources to national priorities in the space and defense industries, and like the Soviets, showed this can work.

State planners in the USSR were not able to successfully apply the technologies developed in one area to other areas the way the Americans did spectacularly well. American space and defense tech and researchers in American universities often interacted and many left to create a myriad of commercial applications in creative directions Soviet planners would never have dreamed of.

Backed by American capital, the tech often went on to find commercial success, providing even more funding to further advance and create new products, creating a positive feedback loop.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

By the 1970s the Soviet Union simply could not keep up. Semiconductor technology accelerated rapidly in the US, developing an ever-increasing array of consumer electronics in calculators, computers and video games. The mass market made technologies the Soviets struggled to master even at great cost cheap and abundant in the US.

These technologies were snapped up and utilized by the very defense and space industries whose initial breakthroughs led to their initial creation.

MADE IN CHINA 2025

The system imposed by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is a hybrid Soviet-American system with Chinese characteristics.

The Chinese have learned one crucial lesson from both the Soviet Union and the Americans in the Cold War, which is to secure essential industries and materials necessary for national security. Following the collapse of the Soviet Bloc, the US forgot this key concept and lazily assumed that the free market would take care of everything.

Early on, the CCP prioritized monopolizing control of key minerals and rare earths, either by owning the means of extraction, the means of production, or both. They also prioritized key industries that would be required in wartime, such as steel and aluminum.

Like the Americans prioritizing and diverting resources to the space and defense industries, the Chinese have done the same but on a vastly grander scale. They have spent lavishly to subsidize and eventually control industrial supply chains to the point it is estimated they control around 30 percent of the world’s manufacturing capacity today.

It is estimated that China’s annual shipbuilding capacity in 2023 was 33 million gross tonnes. The rest of the world accounted for only 32 million tonnes, with the US ranking 14th accounting for only .10 percent of the world’s capacity at just under 65,000 tonnes.

Once the Chinese had mastered those relatively simpler technologies, in 2015 Xi Jinping (習近平) launched the “Made in China 2025” strategic economic plan to initially reduce reliance on foreign technology, moving toward the goal of leading the world technologically.

Though they are still generations behind in their goal of dominating advanced semiconductors, they are increasingly dominating the lower-end chips that power refrigerators and toasters, which are still strategically valuable.

On their other goals, they have made considerable progress and in many cases achieved success. Among other things, Chinese robotics, solar panels, AI, electric cars and high-speed rail are world-class.

In an Australian Strategic Policy Institute report on research papers and research institutions, they assessed that China led the world in 37 of 44 key technologies. In some cases, they lack the experience and precision technology to manufacture these products in the real world but they are working hard on closing this gap.

CREATIVE PROBLEM SOLVERS

Like the Soviet Union, the CCP is obsessed with absolute control and setting national priorities. Big tech companies in China were often spun off from the People’s Liberation Army and most are partly or mostly owned by the government. CCP cells are required to operate in these firms, and CCP political priorities must be obeyed by law.

Though they have largely replaced venture capital with government subsidies and benefits, they have learned from the Americans to allow these firms to be creative and follow market opportunities as long as they do not contradict CCP priorities. This allows for flexibility, innovation and ability to raise capital from selling products on the free market — and if they can flood international markets with subsidized products that drive foreign competitors out of business, so much the better.

Until recently, it was frequently claimed that the Chinese were only capable of copying and stealing intellectual property. Hearing this, I would always shake my head.

While it is true they did a lot of both in an often illegal and predatory manner, writing off Chinese talent and capabilities is a mistake when they are given some latitude to create on their own and are not too weighed down by corruption.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s I was the country manager for both China and Taiwan for an American software outsourcing firm. Most of my employees were software coders.

As coders, they had two problems. At the time, they still had not quite understood capitalism well enough to get the concept of “customer-friendly” design and approached it as an engineering problem, which was a struggle. The other was that they hated properly documenting their code, which I suspect was a ploy to ensure that they would become indispensable by making it harder for other coders to follow the logical flow.

But in creative problem-solving, they were excellent and enjoyed the challenge.

The CCP learned from the Soviets an obsession with maintaining control, but from the Americans not stifling innovation and tapping consumer markets to keep the money flowing.

Donovan’s Deep Dives is a regular column by Courtney Donovan Smith (石東文) who writes in-depth analysis on everything about Taiwan’s political scene and geopolitics. Donovan is also the central Taiwan correspondent at ICRT FM100 Radio News, co-publisher of Compass Magazine, co-founder Taiwan Report (report.tw) and former chair of the Taichung American Chamber of Commerce. Follow him on X: @donovan_smith.

From the last quarter of 2001, research shows that real housing prices nearly tripled (before a 2012 law to enforce housing price registration, researchers tracked a few large real estate firms to estimate housing price behavior). Incomes have not kept pace, though this has not yet led to defaults. Instead, an increasing chunk of household income goes to mortgage payments. This suggests that even if incomes grow, the mortgage squeeze will still make voters feel like their paychecks won’t stretch to cover expenses. The housing price rises in the last two decades are now driving higher rents. The rental market

July 21 to July 27 If the “Taiwan Independence Association” (TIA) incident had happened four years earlier, it probably wouldn’t have caused much of an uproar. But the arrest of four young suspected independence activists in the early hours of May 9, 1991, sparked outrage, with many denouncing it as a return to the White Terror — a time when anyone could be detained for suspected seditious activity. Not only had martial law been lifted in 1987, just days earlier on May 1, the government had abolished the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of National Mobilization for Suppression of the Communist

Fifty-five years ago, a .25-caliber Beretta fired in the revolving door of New York’s Plaza Hotel set Taiwan on an unexpected path to democracy. As Chinese military incursions intensify today, a new documentary, When the Spring Rain Falls (春雨424), revisits that 1970 assassination attempt on then-vice premier Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國). Director Sylvia Feng (馮賢賢) raises the question Taiwan faces under existential threat: “How do we safeguard our fragile democracy and precious freedom?” ASSASSINATION After its retreat to Taiwan in 1949, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) regime under Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) imposed a ruthless military rule, crushing democratic aspirations and kidnapping dissidents from

Fundamentally, this Saturday’s recall vote on 24 Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers is a democratic battle of wills between hardcore supporters of Taiwan sovereignty and the KMT incumbents’ core supporters. The recall campaigners have a key asset: clarity of purpose. Stripped to the core, their mission is to defend Taiwan’s sovereignty and democracy from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). They understand a basic truth, the CCP is — in their own words — at war with Taiwan and Western democracies. Their “unrestricted warfare” campaign to undermine and destroy Taiwan from within is explicit, while simultaneously conducting rehearsals almost daily for invasion,