While riding a scooter along the northeast coast in Yilan County a few years ago, I was alarmed to see a building in the distance that appeared to have fallen over, as if toppled by an earthquake.

As I got closer, I realized this was intentional. The architects had made this building appear to be jutting out of the Earth, much like a mountain that was forced upward by tectonic activity. This was the Lanyang Museum (蘭陽博物館), which tells the story of Yilan, both its natural environment and cultural heritage.

The museum is worth a visit, if only just to get a closer look at the exterior of the building, which won the 2010 Taiwan Architecture Award. The museum’s stated mission is to serve as a gateway to understanding Yilan County, which is itself the real museum. And what better way is there to enter this symbolic gateway than through a building that is itself a symbol of Yilan’s physical form?

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

The various gray tones on the outside wall towering above the museum’s small lake are a scaled-down version of the mighty cliffs that line Taiwan’s northeast coast. The visual effect is stunning, both from afar and from up close. The angle of the outside walls and sloped roof make it seem almost impossible that the interior could be a practical space, but step inside and you’ll see that the clever design does work.

Once inside, you’ll also go beyond a superficial physical understanding of Yilan and start to explore its cultural heritage. From now until April 8, this starts with a photography exhibit commemorating the centennial of the railroad’s Yilan Line from Badu (八堵) to Suao (蘇澳). These high-quality photos were taken in the 1920s by a Japanese engineer who worked on this line’s construction. The exhibit is in the entrance hall and does not require a ticket.

THE LAND

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

The paid visit begins with a small exhibit on the geology, flora and fauna of Yilan, but focuses more heavily on the human (especially Han) use of the land. The butterfly exhibit is, unfortunately, so poorly lit that it is probably ignored by many visitors. On the other hand, the bird call exhibit is much more informative. Do you know what the Mikado pheasant (the bird on the NT$1,000 bill) sounds like? What about the Taiwan yuhina or the Taiwan liocihla? With the clear recordings available to play on-demand, visitors can quickly learn to impress others with their ornithological prowess.

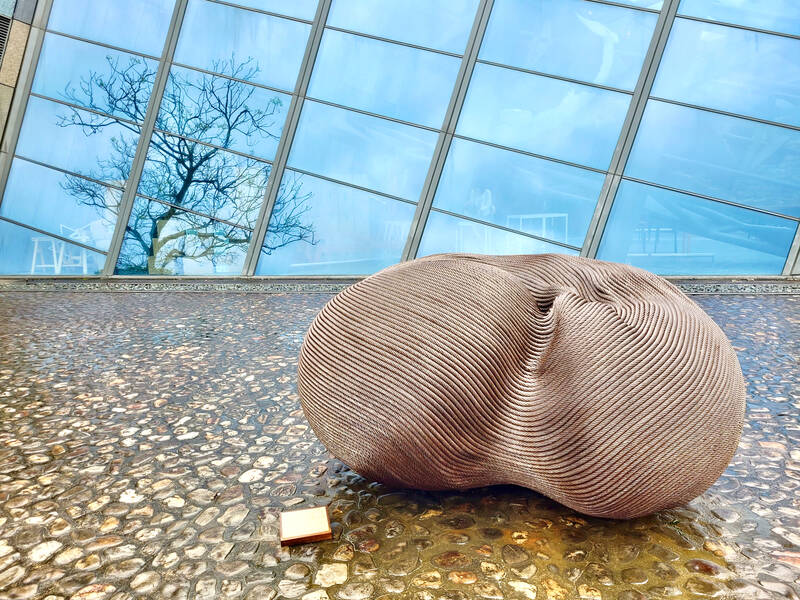

As for flora, the museum teaches about the giant cypress trees that were common in Yilan’s primeval forests, but mostly in the context of their value to logging operations. Real cypress wood is on display here, too, but in the form of an art exhibit. Specific sections of cypress full of whorls, twists and odd protrusions or indentations were identified by the artist for their resemblance to another natural object, and then cut out and given an attractive finish.

Besides logging, land in Yilan was also cleared for farming. One room displays an indigenous Atayal village and shows how they farmed to supplement their diet. Their technique for sustainable agriculture was to plant alder trees to replenish the nutrients in the soil after a certain area became unproductive for their crops. Han farming techniques are given much more attention.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

One of the larger and more ingenious farming artifacts is a water ladder, used to irrigate Yilan’s rice paddies. Because of its long overall shape with paddles placed at regular intervals, somewhat resembling vertebrae on an enormous spine, it is known locally as a “dragon bone waterwheel” (龍骨水車).

Yilan farmers even managed to recruit ducks to help the rice grow better. All it took was a bit of rice on the ground — which happened anyway, as some of the crop inevitably fell to the ground during harvest — and the ducks they released would happily wander around cleaning it up. Eliminating these grains did not help future crops grow better, of course, but the ducks did leave a fair amount of natural fertilizer behind while waddling around in the paddy.

THE SEA

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

While rice growing has always been an important part of Yilan’s economy, residents have also had a close relationship with the sea, and the museum showcases this with the help of its largest single artifact, a full-size harpoon boat made of cypress.

This boat is the main attraction for many visitors as you can board it to get a closer look at its features. Check out the boat’s “freezer,” a compartment that was loaded with nearly two tons of ice before a long fishing trip, to help preserve the catch as well as the crew’s own food. The mannequins on board give a sense of how difficult this type of work was, especially for the harpooner.

Protruding from the bow of this boat is a narrow platform on which the harpooner stands, holding his weapon at the ready and carefully maintaining his balance as the boat is rocked by waves on the open ocean, until it can be maneuvered close enough to a large fish for him to launch the harpoon by hand. This technique is used to catch larger fish like ocean sunfish, sharks and swordfish.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

Other methods of improving catches in the rich waters of the Pacific Ocean have been used by Yilan residents over the years. In the 1950s, one clever fisherman decided to cut a bamboo fishing raft in half so that he and his fishing partner would have two smaller rafts from which to fish, potentially doubling their chances of making a good catch.

When this proved successful, others started to imitate their method, eventually piling as many as 12 small bamboo rafts onto one large boat. When they arrived at their designated fishing area, the one-man rafts would be launched and spread out, dramatically widening the area they could cover. One of these piggybacking rafts, known in Hoklo (more commonly known as Taiwanese) as tiotsoa (釣槽仔), has been set up in the museum to look as if it is in the middle of a day of fishing, suspended a meter above the floor and loaded with the necessary equipment.

Many visitors will not be familiar with the wide variety of fish that are caught in Yilan’s waters, so the museum has a mock fish market set up with stuffed fish, each labeled with the Chinese and scientific names and colored realistically. A video also introduces a more unusual inhabitant of Yilan’s waters, around the volcanically active Turtle Island (龜山島). This crab, Xenograpsus testudinatus, was first described by Taiwanese scientists in 2000, and thrives in the hot, acidic waters next to hydrothermal vents.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

Oct. 27 to Nov. 2 Over a breakfast of soymilk and fried dough costing less than NT$400, seven officials and engineers agreed on a NT$400 million plan — unaware that it would mark the beginning of Taiwan’s semiconductor empire. It was a cold February morning in 1974. Gathered at the unassuming shop were Economics minister Sun Yun-hsuan (孫運璿), director-general of Transportation and Communications Kao Yu-shu (高玉樹), Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) president Wang Chao-chen (王兆振), Telecommunications Laboratories director Kang Pao-huang (康寶煌), Executive Yuan secretary-general Fei Hua (費驊), director-general of Telecommunications Fang Hsien-chi (方賢齊) and Radio Corporation of America (RCA) Laboratories director Pan

The consensus on the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chair race is that Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) ran a populist, ideological back-to-basics campaign and soundly defeated former Taipei mayor Hau Lung-bin (郝龍斌), the candidate backed by the big institutional players. Cheng tapped into a wave of popular enthusiasm within the KMT, while the institutional players’ get-out-the-vote abilities fell flat, suggesting their power has weakened significantly. Yet, a closer look at the race paints a more complicated picture, raising questions about some analysts’ conclusions, including my own. TURNOUT Here is a surprising statistic: Turnout was 130,678, or 39.46 percent of the 331,145 eligible party

The classic warmth of a good old-fashioned izakaya beckons you in, all cozy nooks and dark wood finishes, as tables order a third round and waiters sling tapas-sized bites and assorted — sometimes unidentifiable — skewered meats. But there’s a romantic hush about this Ximending (西門町) hotspot, with cocktails savored, plating elegant and never rushed and daters and diners lit by candlelight and chandelier. Each chair is mismatched and the assorted tables appear to be the fanciest picks from a nearby flea market. A naked sewing mannequin stands in a dimly lit corner, adorned with antique mirrors and draped foliage

The older you get, and the more obsessed with your health, the more it feels as if life comes down to numbers: how many more years you can expect; your lean body mass; your percentage of visceral fat; how dense your bones are; how many kilos you can squat; how long you can deadhang; how often you still do it; your levels of LDL and HDL cholesterol; your resting heart rate; your overnight blood oxygen level; how quickly you can run; how many steps you do in a day; how many hours you sleep; how fast you are shrinking; how