Feb 24 to March 2

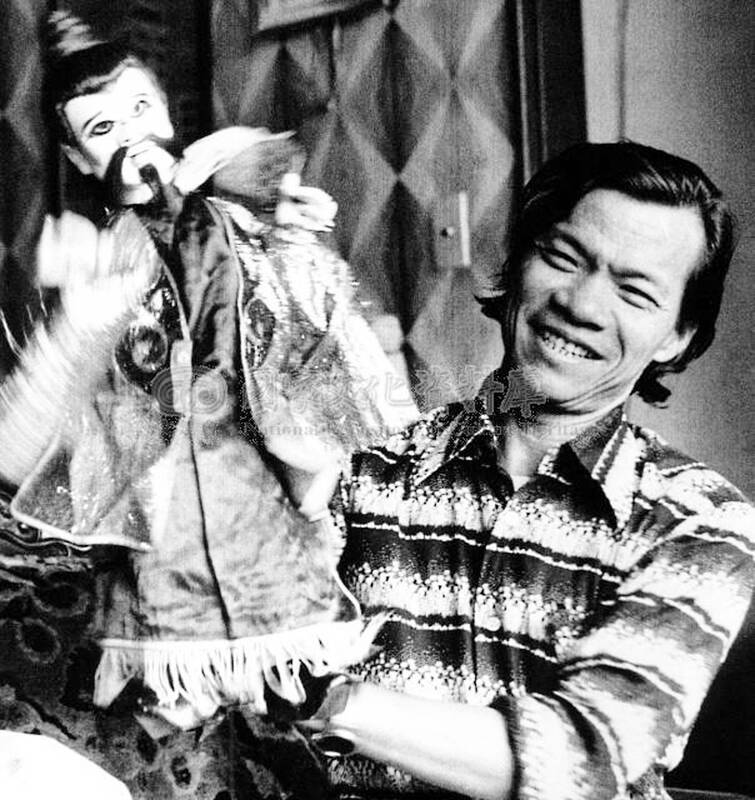

It’s said that the entire nation came to a standstill every time The Scholar Swordsman (雲州大儒俠) appeared on television. Children skipped school, farmers left the fields and workers went home to watch their hero Shih Yen-wen (史艷文) rid the world of evil in the 30-minute daily glove puppetry show. Even those who didn’t speak Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) were hooked.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Running from March 2, 1970 until the government banned it in 1974, the show made Shih a household name and breathed new life into the faltering traditional puppetry industry. It wasn’t the first time puppet theater was shown on television, nor was Shih a new character, but puppeteer Huang Chun-hsiung’s (黃俊雄) creativity and willingness to experiment with modern technology gained the artform an entirely new audience.

Huang not only introduced all sorts of special effects and dynamic backdrops, he enlarged the puppets and gave them movable eyes and mouths for close-up shots. He also eschewed traditional instrumentation for a pre-recorded, modern soundtrack — for example, Shih’s entrance music was from the 1960 Hollywood film Exodus.

But the show’s essential puppeteering techniques and performance style remained rooted in tradition.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

As Huang’s father — legendary puppet master Huang Hai-tai (黃海岱), who was also an innovator — once said: “While we shouldn’t skimp on tradition, we need fresh creativity to keep our audience on their toes. The best ratio is 30 percent classical, 70 percent modern.”

Huang Chun-hsiung’s sons continued to devise new ways to keep the artform relevant, going on to form the Pili (霹靂) puppetry enterprise that still thrives today.

A ‘PERFECT HERO’

Photo courtesy of Yunlin County Department of Culture and Tourism

The Scholar Swordsman, Shih Yen-wen: Handbook and Collections (雲州大儒俠史艷文圖鑑與典藏特輯) describes Shih as a “perfect hero” who gave Taiwanese viewers a sense of release and hope during a time of strict social control under martial law.

Shih was a scholarly gentleman who possessed an all-powerful “Pure Yang Palm” technique; he was also well versed in swordsmanship and could use any object as a weapon. He used strategy to outsmart his foes, and knew when to show his true power and when to lay low. Whenever he met a redeemable enemy, he would go out of his way to help, but he never hesitated to kill anyone who was bad to the bone. He followed a strict moral code of loyalty, righteousness and piety, and sought to rid the world of evil and eliminate all threats to his country and loved ones. Despite his selflessness and lack of fear, he always kept his wits and prevailed in every adventure.

“Shih was a near-perfect person that would never exist in real life, but Huang Chun-hsiung insisted that society needed such a character to inspire the general populace,” the book states.

Photo courtesy of Yunlin County Department of Culture and Tourism

Shih was originally created by Huang Hai-tai in the 1920s, based on Wen Su-chen (文素辰), the hero of the Qing Dynasty novel Humble Words of a Rustic Elder (野叟曝言). Since the story involved Wen leading an army to Japan to fight pirates, which would anger the colonial authorities, Huang Hai-tai rewrote the plot while keeping the essential spirit of the tale.

Huang Hai-tai named the character Shih Tan-yun (史淡雲), devising a 10-episode stage production for him titled Story of Loyalty, Bravery, Filial Piety and Righteousness (忠勇孝義傳).

FAMILY OF NONCONFORMISTS

Photo: Huang Shu-li, Taipei Times

Huang Hai-tai had already been innovating at his Wuzhou Puppet Theater (五洲). Instead of adapting classical Chinese legends, he created original scripts based on popular novels and tales, adding in elements of mysticism and beefing up the fight scenes. He reduced the opera singing and focused on action, storytelling and character development, and this new style quickly caught on in central and southern Taiwan.

The Japanese authorities restricted puppet theater and other traditional arts after 1937, leading to a lull in development until after World War II — although the Huangs continued to perform in secret.

In 1952, a 19-year-old Huang Chun-hsiung established his own troupe. He renamed Shih Tan-yun as Shih Yen-wen and rewrote the script into the lengthy Scholar Swordsman (雲州大儒俠), keeping only three characters from his father’s version.

Huang Chun-hsiung and his father’s other disciples continued evolving the art of glove puppetry, adding three-dimensional backdrops as well as flashy effects and lighting. This souped-up product was called “Jingang Theater” (金剛戲).

According to Huang Hai-dai’s Life of Puppetry (掌上風雲一世紀: 黃海岱的布袋戲生涯), during the 1960s nearly every township had a theater dedicated to the genre. But as the decade drew to a close, the industry stagnated because troupes kept rehashing the same material.

During this time, Huang Chun-hsiung made a decision that shocked his colleagues: he did away with live musicians, replacing them with recordings of original and pop tunes. It turned out to be the right decision, as the number of trained musicians was on the decline.

Huang produced three movies between 1958 and 1968, creating life-size puppets to match the scale of the real-life sets. The films flopped, but he later modified these jumbo puppets into smaller, easily controllable versions best-suited for live-action television filming.

TELEVISION HEROES

Taiwan entered the television age in 1962, and Taiwan Television (台視, TTV) immediately brought on puppet master Lee Tien-lu (李天祿) for regular live performances.

Cheng Lung-ting (陳龍廷) writes in “Study on Huang Chun-hsiung’s television puppet shows” (黃俊雄電視布袋戲研究) that Lee transposed his stage show onto the screen without modification, and the program failed to win many viewers. Unable to cope with the constraints of television, Lee and other puppeteers left the station.

In 1970, Huang Chun-hsiung proposed an effects-laden, live-action version of The Scholar Swordsman to TTV. The station was skeptical, but the deputy programing manager had seen his live performances before and persuaded the top brass to give it a try.

It was a hit, achieving a record rating of 97 percent. However, the authorities shut it down after 583 episodes on the grounds that it impeded the productivity of the nation’s farmers and workers. They were also concerned that the program would impede the learning of Mandarin, a major policy of the government.

Huang returned to the stage, and tried his hand at a Mandarin television show to little success. The ban was lifted in 1982, and soon each of the three free-to-air channels featured a puppet program run by Huang or one of his sons.

However, they still faced many constraints from government censors (they wanted more sensational plots, exaggerated fight scenes and sexual innuendo), so the Huangs set up a production studio in Yunlin County and began directly releasing the shows on videotape.

In 1995, Huang Chun-hsiung’s sons Huang Wen-tse (黃文擇) and Huang Chiang-hua (黃強華) launched the Pili cable channel with new characters and cutting edge production.

Huang Chiang-hua (黃強華) writes in Celebration of Pili (霹靂盛典) that they tried to continue Shih’s story, but they felt that their father had already actualized the character to its maximum potential. Instead of the straight-shooting Shih, they decided that a morally ambiguous hero would be more appealing to modern audiences, coming up with Su Huan-chen (素還真), whose adventures continue today.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

This is the year that the demographic crisis will begin to impact people’s lives. This will create pressures on treatment and hiring of foreigners. Regardless of whatever technological breakthroughs happen, the real value will come from digesting and productively applying existing technologies in new and creative ways. INTRODUCING BASIC SERVICES BREAKDOWNS At some point soon, we will begin to witness a breakdown in basic services. Initially, it will be limited and sporadic, but the frequency and newsworthiness of the incidents will only continue to accelerate dramatically in the coming years. Here in central Taiwan, many basic services are severely understaffed, and

Jan. 5 to Jan. 11 Of the more than 3,000km of sugar railway that once criss-crossed central and southern Taiwan, just 16.1km remain in operation today. By the time Dafydd Fell began photographing the network in earnest in 1994, it was already well past its heyday. The system had been significantly cut back, leaving behind abandoned stations, rusting rolling stock and crumbling facilities. This reduction continued during the five years of his documentation, adding urgency to his task. As passenger services had already ceased by then, Fell had to wait for the sugarcane harvest season each year, which typically ran from

It is a soulful folk song, filled with feeling and history: A love-stricken young man tells God about his hopes and dreams of happiness. Generations of Uighurs, the Turkic ethnic minority in China’s Xinjiang region, have played it at parties and weddings. But today, if they download it, play it or share it online, they risk ending up in prison. Besh pede, a popular Uighur folk ballad, is among dozens of Uighur-language songs that have been deemed “problematic” by Xinjiang authorities, according to a recording of a meeting held by police and other local officials in the historic city of Kashgar in

It’s a good thing that 2025 is over. Yes, I fully expect we will look back on the year with nostalgia, once we have experienced this year and 2027. Traditionally at New Years much discourse is devoted to discussing what happened the previous year. Let’s have a look at what didn’t happen. Many bad things did not happen. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) did not attack Taiwan. We didn’t have a massive, destructive earthquake or drought. We didn’t have a major human pandemic. No widespread unemployment or other destructive social events. Nothing serious was done about Taiwan’s swelling birth rate catastrophe.