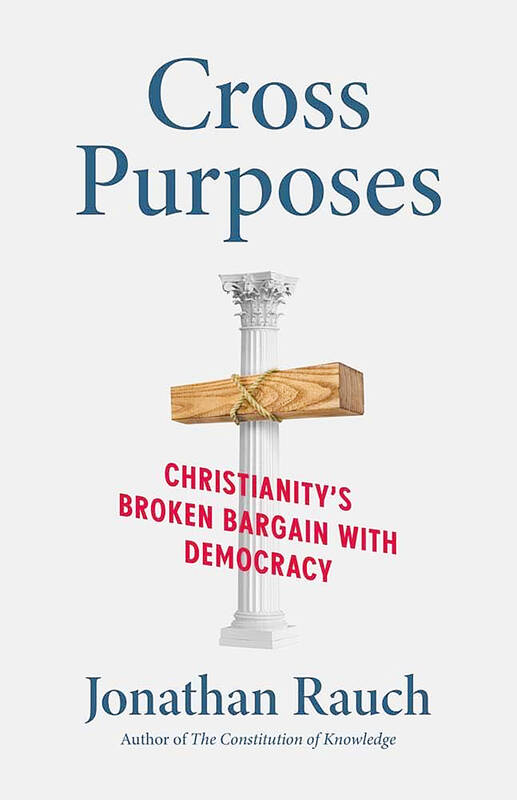

“What happens to our liberal democracy if American Christianity is no longer able, or no longer willing, to perform the functions on which our constitutional order depends?” Jonathan Rauch asks in the opening pages of Cross Purposes. “The alarming answer is that the crisis for Christianity has turned out to be a crisis for democracy.”

Rauch is a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and a contributor to the Atlantic Monthly. Author of more than a dozen books, he is gay, Jewish and an atheist. The questions he poses are personal, even existential. He places his own identity and experience at the fore.

“I feel an immense pride in America’s pluralism and tolerance while remaining conscious … of my status as a minority and an outsider,” Rauch explains. “I feel that my sense of belonging to America does not translate into a sense that America belongs to me.”

He loves the US but is now uncertain the country loves him back. The seemingly gentle mainline Protestantism that undergirded the US during the 1960s and 1970s gave way to something more jagged. Harsher and angrier, this Christianity is also less secure in its primacy of place, a cudgel fused to blood and soil.

“All nations before him are as nothing; and they are counted to him less than nothing, and vanity,” the prophet Isaiah once declared, seemingly forgotten by the Christian nationalists of today. Then again, scripture is read in myriad ways.

‘CHURCH OF FEAR’

Rauch labels the current iteration “Sharp Christianity, the Church of Fear.” It wields power, reaches into the Oval Office, yet sees itself besieged. It decries modernity and is very much of it.

Sharp Christianity proclaims the word of God and makes deities of flesh and blood, in Rauch’s telling. At the Capitol on Jan. 6, markers of Christianity and paganism stood adjacent to the gallows.

Franklin Graham, son of the late Billy Graham, threatens Americans with God’s wrath if they criticize Donald Trump.

“The Bible says it is appointed unto man once to die and then the judgment,” he posted to Facebook.

Another famous scion, the disgraced Jerry Falwell Jr, admonished his flock to stop electing “nice guys.” Instead, he tweeted: “The US needs streetfighters like Donald Trump at every level of government.”

In such words, resentment and grievance supplant the Bible and “What would Jesus do?”

Then again, amid the carnage of the actual civil war, all combatants looked to Christianity for justification and succor.

“Both read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other,” Lincoln observed, in his second Inaugural. “The prayers of both could not be answered — that of neither has been answered fully.”

The Battle Hymn of the Republic, by Julia Ward Howe, an abolitionist, sings of “His terrible swift sword,” leaving no room for ambivalence or ambiguity. “As he died to make men holy, let us die to make men free / While God is marching on.”

At the same time, below the Mason-Dixon line, churches and stained-glass windows paid homage to Robert E Lee and Stonewall Jackson. The cross, the flag and the slaver’s whip were beatifically stitched together.

Rauch also engages in personal soul-searching.

“I was smug about secularization,” he confesses. “I began bending an ear to warnings that Christianity’s crisis is democracy’s, too. I came to realize that in American civic life, Christianity is a load-bearing wall. When it buckles, all the institutions around it come under stress, and some of them buckle, too.”

By the numbers, religious “nones,” at 28 percent of the US population, exceed evangelical Protestants (24 percent) and non-evangelicals (16 percent). Attendance at worship drops. Twenty years ago, according to Gallup, 42 percent of US adults attended religious services every week or nearly every week. By the middle of the 2010s, it was 38 percent. Now, only three in 10 regularly fill the pews.

“Both of its major streams, the ecumenical and the evangelical, have ‘thinned,’ that is, secularized, albeit in very different ways,” Rauch writes. “Neither is as capable of providing meaning and moral grounding as it once was or today needs to be, and secular alternatives like science and SoulCycle cannot, even in principle, fill the void.”

He acknowledges that he did not fully comprehend America’s civic religion.

‘WALL OF SEPARATION’

“I did not appreciate the implicit bargain between American democracy and American Christianity,” he states. “I would have said that the basic deal was to leave each other alone — ‘wall of separation’ and all that. Their only bargain, I thought, was to make no bargain; to the greatest extent possible, religion and government should tend to their separate businesses and not interfere with each other.”

That take hasn’t aged well.

Protestantism was part of America’s big bang. Religious turmoil in England coincided with the first rounds of migration to the New World. The American revolution owed a particular debt of gratitude to Protestant dissenters. Colonial Congregationalists and Presbyterians came to owe little allegiance to the crown, less to Canterbury. Later, battles over slavery, prohibition, civil rights and the Vietnam war also played out within America’s churches. Those divisions have remained. Not all wounds heal.

Rauch points to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints and its capacity for compromise as a possible model for other segments of Christianity to follow. But personal conservatism and social cohesion are born of Mormon homogeneity and conformity. Voluntary safety nets spring from self-identification with their beneficiaries. As Jonathan Haidt of New York University has repeatedly observed, diversity and cohesion seldom go hand in hand.

The US marks its 250th birthday on 4 July next year. From the vantage points of 21st-century America, looking back over two millennia provides no clear solution.

Wooden houses wedged between concrete, crumbling brick facades with roofs gaping to the sky, and tiled art deco buildings down narrow alleyways: Taichung Central District’s (中區) aging architecture reveals both the allure and reality of the old downtown. From Indigenous settlement to capital under Qing Dynasty rule through to Japanese colonization, Taichung’s Central District holds a long and layered history. The bygone beauty of its streets once earned it the nickname “Little Kyoto.” Since the late eighties, however, the shifting of economic and government centers westward signaled a gradual decline in the area’s evolving fortunes. With the regeneration of the once

Even by the standards of Ukraine’s International Legion, which comprises volunteers from over 55 countries, Han has an unusual backstory. Born in Taichung, he grew up in Costa Rica — then one of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies — where a relative worked for the embassy. After attending an American international high school in San Jose, Costa Rica’s capital, Han — who prefers to use only his given name for OPSEC (operations security) reasons — moved to the US in his teens. He attended Penn State University before returning to Taiwan to work in the semiconductor industry in Kaohsiung, where he

On May 2, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), at a meeting in support of Taipei city councilors at party headquarters, compared President William Lai (賴清德) to Hitler. Chu claimed that unlike any other democracy worldwide in history, no other leader was rooting out opposing parties like Lai and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). That his statements are wildly inaccurate was not the point. It was a rallying cry, not a history lesson. This was intentional to provoke the international diplomatic community into a response, which was promptly provided. Both the German and Israeli offices issued statements on Facebook

Perched on Thailand’s border with Myanmar, Arunothai is a dusty crossroads town, a nowheresville that could be the setting of some Southeast Asian spaghetti Western. Its main street is the final, dead-end section of the two-lane highway from Chiang Mai, Thailand’s second largest city 120kms south, and the heart of the kingdom’s mountainous north. At the town boundary, a Chinese-style arch capped with dragons also bears Thai script declaring fealty to Bangkok’s royal family: “Long live the King!” Further on, Chinese lanterns line the main street, and on the hillsides, courtyard homes sit among warrens of narrow, winding alleyways and