Feb. 10 to Feb. 16

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute

More than three decades after penning the iconic High Green Mountains (高山青), a frail Teng Yu-ping (鄧禹平) finally visited the verdant peaks and blue streams of Alishan described in the lyrics.

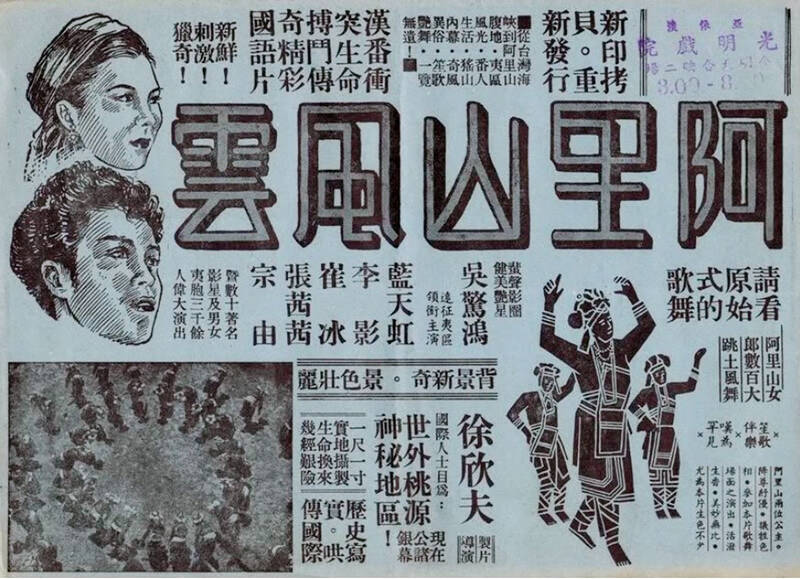

Often mistaken as an indigenous folk song, it was actually created in 1949 by Chinese filmmakers while shooting a scene for the movie Happenings in Alishan (阿里山風雲) in Taipei’s Beitou District (北投), recounts director Chang Ying (張英) in the 1999 book, Chang Ying’s Contributions to Taiwanese Cinema and Theater (打鑼三響包得行: 張英對台灣影劇的貢獻).

The team was meant to return to China after filming, but news soon came that Shanghai, where their headquarters were located, was about to fall to the Chinese communists. All but two members declined to return home, opting to stay and complete the movie independently. Happenings in Alishan premiered at Taipei’s Zhongshan Hall on Feb. 16, 1950, inadvertently becoming the first Mandarin movie to be entirely produced in Taiwan.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute

Even though the story featured the Tsou people, the principal actors all hailed from China and filming was done almost entirely in Hualien, featuring instead Amis dancers and festivals. When co-director Chang Cheh (張徹) needed words to the songs he composed for the film, he turned to Teng, a young poet from China’s Sichuan Province who was barely familiar with Taiwan. Teng was part of the crew and played a minor role in the film.

Chang Ying writes that he changed some of the words, adding, “I never thought that a song three amateurs cobbled together would be mistaken as a folk song and become famous even in China. Today, it’s often sung there to welcome visitors from Taiwan.”

Happenings in Alishan was not only influential to the development of Taiwan’s film scene, both directors would go on to have storied careers: Chang Ying remained in Taiwan and directed or produced more than 40 films, including several Hoklo-language classics (which he did not speak), while Chang Cheh became one of Hong Kong’s top martial arts movie directors.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

TAIWAN MANIA

After World War II, Shanghai resumed its role as China’s Hollywood. Lacking opportunities in his native Sichuan, aspiring auteur Chang Ying moved to the city and joined Cathay Film Company (國泰影業), first as a screenwriter then rising up to director.

Chang writes that there was considerable interest in Taiwan then. In 1947, the company visited for the first time to shoot several scenes for the movie Girl’s Mask (假面女郎), written by Chang Cheh. Lead actress Ku Lan-chun (顧蘭君) showed up at the Taipei premiere, causing such a commotion that the crowd broke through the theatere’s glass doors. Encouraged by the reaction, Cathay set up a branch office in Taiwan.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute

In late 1948, Cathay’s film studio manager Hsu Hsin-fang (徐欣芳) moved his family to Taiwan as the Chinese Civil War intensified, taking over the Taipei office. Chang Ying and Chang Cheh were tasked with bringing a crew over to make a film about Taiwan, as the company was considering relocating here permanently.

While preparing for the trip, Chang Ying read an article in a travel magazine about a temple in Chiayi named after Qing Dynasty-era interpreter Wu Feng (吳鳳), who is said to have sacrificed his life to stop the headhunting practices of the indigenous Tsou. Chang was “very moved” and decided to make this tale the backbone of his film. They later added a love story involving two rival tribes and conflicts with Han settlers, but Wu Feng was undoubtedly the hero.

Three decades later, the tale, read by every child in school, became one of the earliest targets of the indigenous rights movement, as it perpetuated stereotypes of indigenous Taiwanese as backward savages who needed to be “civilized” by the Han Chinese (see “Taiwan in Time: the drastic downfall of Wu Feng,” Sept. 10, 2017).

The sterotype was evident in several paternalistic movie reviews in the Central Daily News that greatly praised Wu Feng’s selfless deed to stop a “barbarous” practice; one writer called for more Wu Fengs to appear to further “improve” the lives of the indigenous peoples.

REMAINING IN TAIWAN

Upon arrival in Taiwan, the crew headed to Alishan, but they found it unsuitable for filming due to the heavy forest cover and towering trees blocking out the sunlight; the scarcity of electricity also made it impossible to set up artificial lights. The area was sparsely populated and they had a hard time finding extras.

Hualien Theater manager Yu Run-hsiang (游潤香), who was visiting the crew to discuss screening rights, suggested that they film in Hualien instead. Yu guaranteed that there would be countless indigenous dancers and singers available, and offered them his jeep and a place to sleep in the theater. He would even provide food.

The crew was sold, and the two directors headed to Beitou to flesh out the script. However, just before shooting was to commence, Cathay announced that it was pulling the project because the People’s Liberation Army was closing in on Shanghai. The company urged the team to return to China and send back the equipment before it was too late.

However, Chang Ying writes that most members decided to stay on, with Hsu personally financing the movie under the newly formed Wanxiang Film Company (萬象影業). A few other film companies had retreated to Taiwan by then, and Wanxiang enlisted some of their experts to help out with the production.

The crew became shareholders of the film, taking no salary but agreeing to split the profits. The film was a success, even showing in Chinatowns in the US during the late 1950s. Wanxiang disbanded afterward and the members went their separate ways.

ICONIC SONG

The movie featured several original songs, all composed by Chang Cheh. The main tune, Ode to Alishan (阿里山頌), was written by Taiwanese poet Chiu Pin-tsun (丘斌存), and the initial footage did not include High Green Mountains, writes film historian and playwright Edwin Chen (陳煒智) in an article for the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute.

Chang Ying writes that after filming wrapped up in Hualien, leading actress Wu Ching-hung (吳驚鴻) began complaining that there were no scenes of her singing in the film as the female vocal duties were performed by Chang Chien-hsi (張茜西), who had formal training. She brought the matter to Hsu, who asked Chang Cheh to add a song for Wu.

The crew then headed to a waterfall in Beitou to film the scene, where Chang and Teng came up with High Green Mountains — at that time it was titled The Girl From Alishan (阿里山的姑娘). However, Chang Ying writes that Wu had trouble staying in key, and Chang Chien-hsi is commonly credited as the original singer (although some sources differ).

In 1952, Chinese composer Hwang Yau-tai (黃友棣) rearranged the tune into Song of Alishan (阿里山之歌). This version was adapted by numerous popular singers and at some point took on the name High Green Mountains. It was also a hit in China, and for a long time it was the one song people there associated with Taiwan.

Over the decades, the song increased in popularity while the movie faded into obscurity, leading to much confusion over its origins, Chen writes. It didn’t help that the original footage of the song nor the film credits were lost; today only 20 minutes of the original movie survives. Only during the 1980s was Teng properly credited for his contribution.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

For many centuries from the medieval to the early modern era, the island port of Hirado on the northwestern tip of Kyushu in Japan was the epicenter of piracy in East Asia. From bases in Hirado the notorious wokou (倭寇) terrorized Korea and China. They raided coastal towns, carrying off people into slavery and looting everything from grain to porcelain to bells in Buddhist temples. Kyushu itself operated a thriving trade with China in sulfur, a necessary ingredient of the gunpowder that powered militaries from Europe to Japan. Over time Hirado developed into a full service stop for pirates. Booty could

Politically charged thriller One Battle After Another won six prizes, including best picture, at the British Academy Film Awards on Sunday, building momentum ahead of Hollywood’s Academy Awards next month. Blues-steeped vampire epic Sinners and gothic horror story Frankenstein won three awards each, while Shakespearean family tragedy Hamnet won two including best British film. One Battle After Another, Paul Thomas Anderson’s explosive film about a group of revolutionaries in chaotic conflict with the state, won awards for directing, adapted screenplay, cinematography and editing, as well as for Sean Penn’s supporting performance as an obsessed military officer. “This is very overwhelming and wonderful,” Anderson

Social media addiction has been compared to casinos, opioids and cigarettes. While there’s some debate among experts about the line between overuse and addiction, and whether social media can cause the latter, there is no doubt that many people feel like they can’t escape the pull of Instagram, TikTok, Snapchat and other platforms. The companies that designed your favorite apps have an incentive to keep you glued to them so they can serve up ads that make them billions of dollars in revenue. Resisting the pull of the endless scroll, the dopamine hits from short-form videos and the ego boost and validation

When sifting through the seemingly endless collection of documents in the Epstein files gets to be too much and Ellie Leonard needs a break, she takes a walk outside. Then it’s back to the computer. The New Jersey mother of four is among hundreds of citizen-journalists, or sleuths, absorbed by the material connected to the late Jeffrey Epstein. She’s determined to learn the stories behind his illicit sex ring and relationships with some of the world’s most powerful people, and publish what she finds on Substack. “I like a good puzzle,” Leonard said. “I like an investigation. I like things that we