Dec 2 to Dec 8

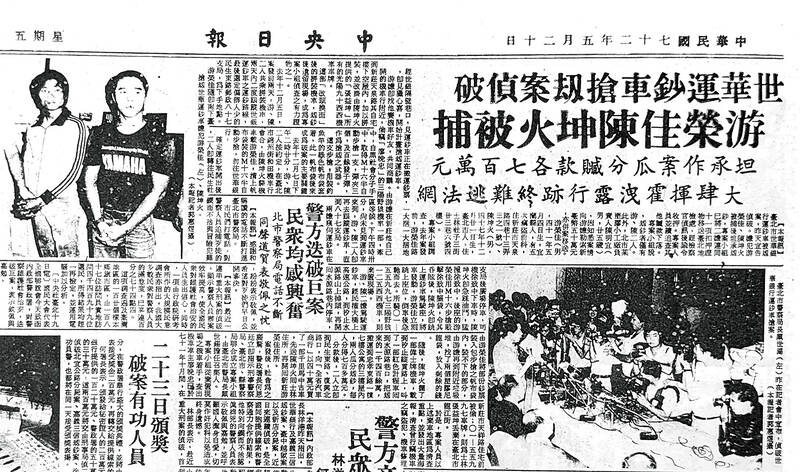

It was the biggest heist in Taiwanese history at that time.

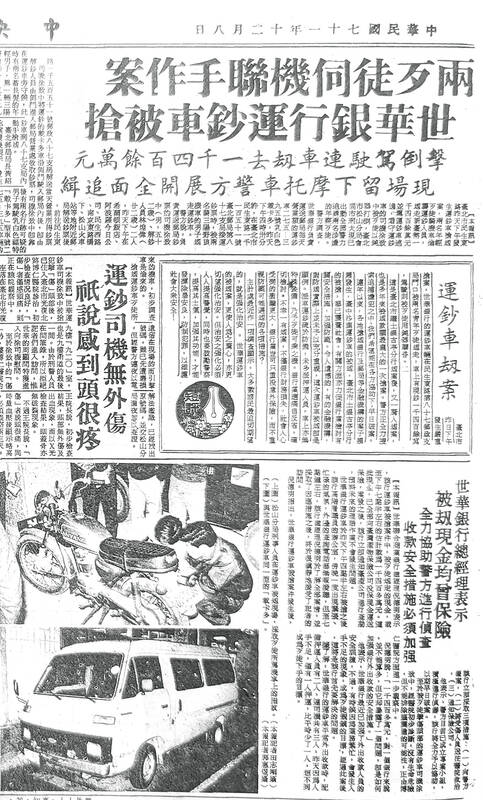

In the afternoon of Dec. 7, 1982, two masked men armed with M16 assault rifles knocked out the driver of a United World Chinese Commercial Bank (世華銀行) security van, making away with NT$14 million (worth about NT$30 million today). The van had been parked behind a post office at Taipei’s Minsheng E Road when the robbers struck, and despite the post office being full of customers, nobody inside had noticed the brazen theft.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

“Criminals robbing a bank truck is something we only see in American Westerns, but yesterday this scene happened on the streets of Taipei,” a United Daily News editorial stated. “In Taiwan, previously a place of law and order, people are now robbing banks, bank trucks and post offices. This is a serious problem that goes beyond whether the police can solve these cases or not.”

Eight months earlier, Taiwan witnessed its first armed bank robbery when Lee Shih-ke (李師科) made off with about NT$5.3 million from the Land Bank of Taiwan’s Guting branch (see “Taiwan in Time: The robber in the sanitary mask,” April 9, 2017). And on the same day as the robbery, gunmen barged into the Chiayi District Court in broad daylight and broke out a detainee.

“There are two reasons for this flurry of crimes: the slumping economy and the societal trend toward extravagance; the pursuit of material pleasures is in vogue,” the editorial said.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

The police apprehended the culprits 163 days later, discovering that it was connected to another robbery committed the previous year in Taichung’s Shalu District (沙鹿). The eight men involved in both cases were executed on July 29, 1983.

FIRST HEIST

Taiwan Cooperative Bank’s Shalu branch usually transported cash in their own truck. But the vehicle was not available on Nov. 24, 1981 when they needed to move NT$6.8 million to another location, and they called a reputable local taxi service to do the job.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

According to the Office of Historical Suspense Investigation and Research (重大歷史懸疑案件調查辦公室), this was not uncommon in those days as bank security was generally lax. After all, violent crimes such as robbery, kidnapping and rape were punished by death under martial law.

The taxi was halfway to its destination when a light blue sedan, which had been tailing it, suddenly blocked its way. Four men armed with knives leapt out, threatened the driver, snatched the car keys, forced the passengers from the car and then drove the taxi away. The whole ordeal took five minutes.

The subsequent investigation led police to Su Chun-mo (蘇俊模), who belonged to an influential local family, and arrested him along with five other suspects 25 days after the crime. Su admitted that he had large gambling debts and had been planning the heist for about a year. They were all sentenced to death by a military court.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Such crimes were unprecedented in Taiwan; so when the United World Chinese Commercial Bank truck was carjacked just over a year later, the police were greatly alarmed. Was this a copycat, or were the two cases connected?

COLD CASE

The second heist proved harder to solve, as Taipei was much larger than Shalu and CCTV cameras were not common then. The United Daily News reported that the cops suspected it to be an inside job, as the bank’s cash transportation schedule and route was known only by upper management. The robbers even knew when post office guards got off work and chose the exact right time to strike.

The truck was meant to pick up cash from eight stops and then return to the bank; the post office was its sixth stop. The driver, who was not supposed to leave the vehicle, was standing next to it waiting for his colleague to retrieve money from the post office when he was struck in the back of the neck with a long object in a canvas bag. In his dazed state, he vaguely saw the two men take out an assault rifle from the bag, yelling at the few people who were on scene to freeze before speeding away. A few postal workers gave chase, but lost sight of the vehicle.

The police only had one clue: a scooter. However, it turned out to be stolen and the serial number had been removed. No fingerprints could be found on the vehicle, leading police to conclude that it had been a carefully planned job.

Meanwhile, Su and his cohorts were living it up in prison because his family bribed the staff. He even paid a doctor to sign him out of the hospital to seek treatment for acute otitis, using the clinic for trysts with his girlfriend. Still, death was near.

In early 1983, Su smuggled a saw into his cell, patiently worked on the bars bit by bit, and in April escaped with five other inmates. They managed to acquire an M16 rifle while on the run, but they were found by police seven days later and sent back to jail after a brief gunfight.

MATCHING RIFLES

The involvement of an M16 in both incidents further convinced the police that they were related. After searching Su’s hiding place, they found a canvas bag that matched a description of the one the United World Chinese Commercial Bank robbers used to conceal the M16.

After questioning the Shalu incident detainees and information from secret witnesses, they directed their attention toward Yu Jung-chia (游榮佳), who was Su’s uncle.

They soon discovered that Yu, who had a lengthy criminal record, had been spending lavishly. His home address was also very close to the place where the scooter was stolen. Finally, one of Su’s cohorts broke under pressure and told the cops about Yu’s involvement. Yu and another alleged accomplice, Chen Kun-huo (陳坤火), were arrested in May 1983 and after intense questioning, both admitted to the crime.

Yu later told reporters that part of his motive was to provide for Su’s legal fees and escape, since the Su family had already spent a great deal of money on the case. Su had helped out Yu financially in the past, and felt obligated to return the favor.

He claimed to have given the Su family a total of NT$4 million, with NT$500,000 going directly to Su after he escaped from jail. As for Chen, he said he needed money for his upcoming wedding. According to Yu, the M16 was provided by a relative of Su, and after the heist they returned it to the family, who gave it to Su once he escaped.

All eight robbers faced the firing squad on the same day. Yu seemed the most repentant, according to the United Daily News, as he left behind a wife and a one-year-old child. In his last words, he told his friends to care for his family and urged his wife to teach his son well, so that he would not follow the same path.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

This is the year that the demographic crisis will begin to impact people’s lives. This will create pressures on treatment and hiring of foreigners. Regardless of whatever technological breakthroughs happen, the real value will come from digesting and productively applying existing technologies in new and creative ways. INTRODUCING BASIC SERVICES BREAKDOWNS At some point soon, we will begin to witness a breakdown in basic services. Initially, it will be limited and sporadic, but the frequency and newsworthiness of the incidents will only continue to accelerate dramatically in the coming years. Here in central Taiwan, many basic services are severely understaffed, and

Jan. 5 to Jan. 11 Of the more than 3,000km of sugar railway that once criss-crossed central and southern Taiwan, just 16.1km remain in operation today. By the time Dafydd Fell began photographing the network in earnest in 1994, it was already well past its heyday. The system had been significantly cut back, leaving behind abandoned stations, rusting rolling stock and crumbling facilities. This reduction continued during the five years of his documentation, adding urgency to his task. As passenger services had already ceased by then, Fell had to wait for the sugarcane harvest season each year, which typically ran from

It is a soulful folk song, filled with feeling and history: A love-stricken young man tells God about his hopes and dreams of happiness. Generations of Uighurs, the Turkic ethnic minority in China’s Xinjiang region, have played it at parties and weddings. But today, if they download it, play it or share it online, they risk ending up in prison. Besh pede, a popular Uighur folk ballad, is among dozens of Uighur-language songs that have been deemed “problematic” by Xinjiang authorities, according to a recording of a meeting held by police and other local officials in the historic city of Kashgar in

It’s a good thing that 2025 is over. Yes, I fully expect we will look back on the year with nostalgia, once we have experienced this year and 2027. Traditionally at New Years much discourse is devoted to discussing what happened the previous year. Let’s have a look at what didn’t happen. Many bad things did not happen. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) did not attack Taiwan. We didn’t have a massive, destructive earthquake or drought. We didn’t have a major human pandemic. No widespread unemployment or other destructive social events. Nothing serious was done about Taiwan’s swelling birth rate catastrophe.