For all the excellent works in English on Taiwan under Japanese colonial rule, there have been few (if any) monographs dedicated to Taiwanese women as imperial subjects.

Studies on the colonial government’s assimilation policy (doka) and, during World War II, its imperial subjectification efforts (kominka) overwhelmingly focus on male subjects.

As part of its southward expansion, the Japanese cultivated networks of Hoklo-speaking businessmen in Taiwan and southern China early in colonial rule. Later, producing committed soldiers became the main goal of education and government propaganda. These two entwined strands of imperial policy — expertly analyzed by Sheiji Shirane in Imperial Gateway (reviewed in Taipei Times, March 30, 2023) — ipso facto targeted men.

Likewise, as this book shows, colonial Taiwan’s social and cultural movements were male-dominated, and studies on this aspect of colonialism reflect this.

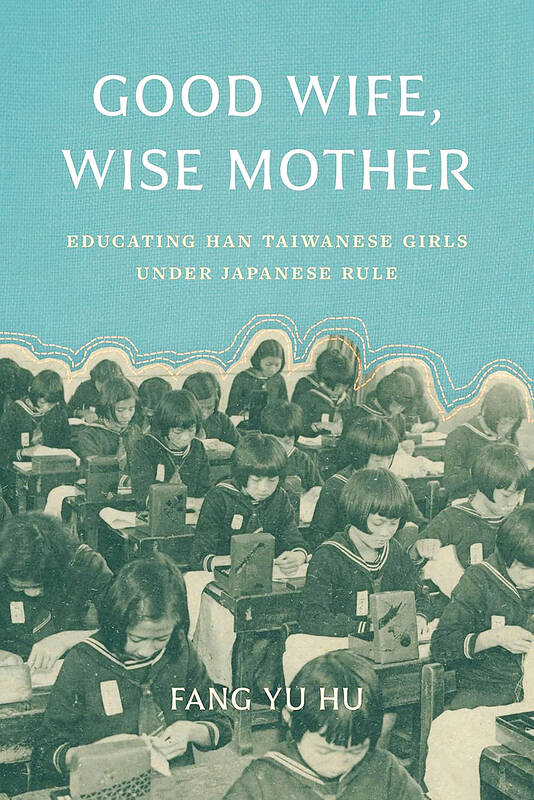

So, this book is overdue, and much of its analysis is valuable. Accompanying her arguments with illustrations from colonial textbooks, Fang Yu Hu shows how gender-specific values and practical knowledge were taught to Taiwanese girls. While there were limited depictions of women in early textbook editions, instances of female characters increased in later imprints. This reflected the increasing numbers of girls in education, writes Hu, an assistant professor of history at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona.

ESTABLISHING ROLES

Enrollments among girls remained as low as 3,000 in 1915, but had increased almost tenfold by 1920, thanks to various strategies by the colonial administration, including home visits to convince mothers of the benefits of literacy, a higher maximum enrollment age and an increase in the number of female teachers. By 1930, more than 56,000 girls were enrolled; within a decade this figure had more than quadrupled.

Among the “gendered messages” communicated by the illustrations is feminine responsibility for sick relatives. One picture shows a young girl tending to her bedridden mother before, the text explains, going to get medicine for her. Another, titled “Doll’s Illness,” shows siblings role playing, with the brother dressed as a doctor and the sister cradling an ailing “infant.”

A third healthcare-related image portrays a boy ill in bed, as a doctor advises his mother that he remains sick because he did not immediately take medicine. Instead, his mother resorted to prayers to deities, unlike the boy’s friend, who suffered the same illness, but recovered fast thanks to a doctor’s prescription.

Reinforced by the physician’s bag and doctor’s garb, the message is clear: Western-style drugs should be trusted over folk superstitions, as part of Japan’s “scientific colonialism.” The brother in the role-playing scenario is dressed in a bowler hat, overcoat and spectacles, while his sister and the doll don traditional Taiwanese garments, emphasizing their primitiveness.

In general, Hu’s argument here seems sound for, as she points out, subsequent textbook editions continued to depict Taiwanese girls in Taiwanese attire, indicating that they “remained ‘backward’ and unchanged, perhaps resistant to change.” There was fear “of the potential damage that uneducated Taiwanese girls and women could do to make doka a failure …”

This was underscored by the campaign against foot-binding, criticized by educators in numerous journal articles as uncivilized and an obstacle to nurturing “strong and healthy mothers” who would, in turn, produce robust Japanese patriots.

Elsewhere, examples of gendered policy seem flimsy. It is hard, for instance, to discern the necessary gender-specificity of an illustration of a girl writing a letter and helping her mother understand postal services. The scene, Hu writes, “reveals that colonial officials expected educated girls to facilitate communication by using modern services.”

This seems obvious; but unlike the images of care giving, cooking and charity, one can easily imagine a young boy occupying the role of scribe and intermediary in the “Postal Service” illustration.

BOLD CLAIMS

If this seems insignificant, it’s symptomatic of a pervasive problem with the text, which sometimes manifests in bold but weakly substantiated statements.

In discussing the development of Taiwanese sociopolitical movements in the 1920s, for example, Hu concludes that activists could “anchor their critique of colonial rule in the purpose and the success of girls’ and women’s education.”

While she cites articles, written mostly by men but also some women, in Taiwan Minbao (originally Taiwan Seinen), the first independent Taiwanese periodical, her claim that colonial critiques were “anchored” in discussions of women’s education is a huge leap.

As is the case in academic works, the incessant ramming home of the thesis can grate — at points it feels like there’s a royalties deal tied to the reiteration of the “good wife, wise mother” mantra. In places, the repetition of the word “gender” also becomes wearisome. The following sentence, which refers to women’s memories of performing domestic chores for Japanese teachers, is indicative: “Their memories and nostalgia were gendered because of their expected gender roles, with their gender being connected to their labor.”

Yet, at its best, Hu’s examination of colonial gender norms is captivating and insightful. Regarding reports of sexual exploitation and abuse of female students, Hu observes that the teachers “represented the colonial authority while schoolgirls represented the Taiwanese people exploited by the Japanese.”

In her introduction to the short story collection A Son of Taiwan (reviewed in Taipei Times, July 14, 2022), Sylvia Li-chun Lin (林麗君) makes a related point about the marriage of a Taiwanese woman to a corrupt minor Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) official in “Potsdam Section Chief,” a tale by Wu Chuo-liu (吳濁流). The union, writes Lin, symbolizes Taiwan’s relationship with China. Interestingly, Wu’s treatment of female characters in his famed novel The Orphan of Asia is highlighted by Hu as an example of the conflicting attitudes of Taiwanese progressives toward the “good wives, wise mothers” paradigm.

A further parallel can be seen in analysis of the work of writer Li Ang (李昂), by scholar Wu Chia-rong (吳家榮), who sees sex between a Taiwanese female protagonist and her Chinese lovers as suggestive of “the original sin imposed on Taiwanese subjects” or “an act of betrayal … to the native soil.”

STARK CONTRASTS

Particularly incisive are the observations on the “social flattening” that the system produced during war mobilization when girls from working class backgrounds planted vegetables alongside classmates from privileged backgrounds. Overall, the system seems to have benefited girls from lower income families who acquired the literacy and skills needed for postwar employment, contributing to Taiwan’s development.

Gathered from interviews in Taiwan and the US, the recollections of these Japanese-educated women are fascinating, with many remembering the era fondly as time of camaraderie among girls across social strata and an era where discipline, manners and respect for authority were paramount.

Many, Hu found, contrasted Japanese moral education (shushin) and the order it created with chaos, corruption and injustice under the KMT. The disdain extended to the youth of today, who were branded self-centered and materialistic.

Ignoring the inherent discrimination of the colonial system — reinforced by the preexisting patriarchy — these women waxed lyrical about an era where education emphasized the collective good, fostering a “social harmony” they felt contemporary society lacked. In this sense, writes Hu, this passing generation of wives and mothers were as much defined by their Japanese education as their Chinese ethnicity.

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not

We have reached the point where, on any given day, it has become shocking if nothing shocking is happening in the news. This is especially true of Taiwan, which is in the crosshairs of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), uniquely vulnerable to events happening in the US and Japan and where domestic politics has turned toxic and self-destructive. There are big forces at play far beyond our ability to control them. Feelings of helplessness are no joke and can lead to serious health issues. It should come as no surprise that a Strategic Market Research report is predicting a Compound