What first caught my eye when I entered the 921 Earthquake Museum was a yellow band running at an angle across the floor toward a pile of exposed soil. This marks the line where, in the early morning hours of Sept. 21, 1999, a massive magnitude 7.3 earthquake raised the earth over two meters along one side of the Chelungpu Fault (車籠埔斷層).

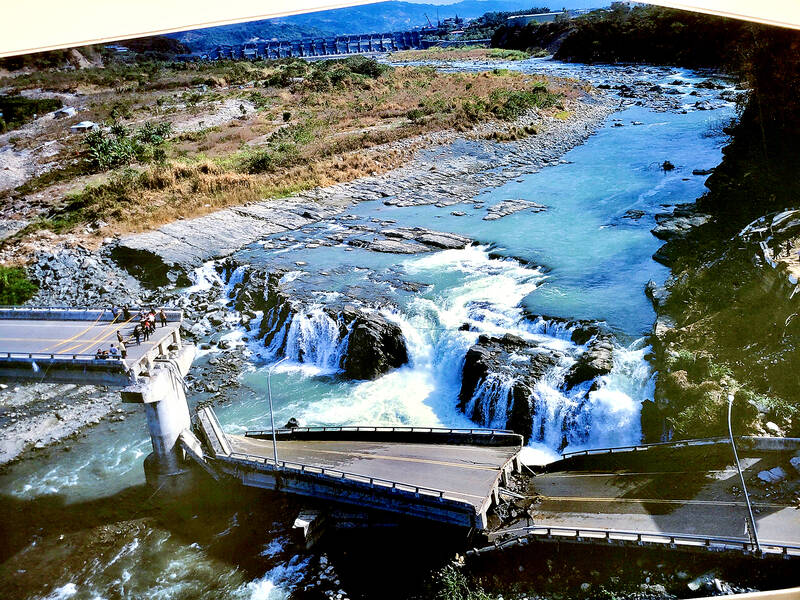

The museum’s first gallery, named after this fault, takes visitors on a journey along its length, from the spot right in front of them, where the uplift is visible in the exposed soil, all the way to the farthest reaches of the uplifting in Miaoli County. The fault is not a straight line but follows an erratic, curved path — reflected in the snakelike shape of this building — as it passes through different soil types and dodges mountains. Photographs show visitors the awesome damage wrought by the 921 Earthquake along the faultline as it toppled buildings, snapped bridges and even bent a dam, as well as the curious sights it created, like the new waterfall that appeared in the Dajia River (大甲溪), and rows of tea plants made crooked by the shifting ground.

The most surprising thing to see was not how bad the damage was along the fault — any time one side of a building gets pushed upward over a meter, total collapse can be expected — but how little damage there was just a hundred meters away from the fault. The aerial views were reminiscent of the aftermath of a tornado, where a line of rubble was often flanked by perfectly intact structures.

Photo: Tyler Cotteni

CONSTRUCTION FAILURES, NEW SOLUTIONS

While the first gallery teaches about the cause of earthquakes and demonstrates their power through the example of the 921 Earthquake, the second gallery focuses on why man-made structures fail and the development of anti-earthquake building techniques over the years. This is the most interactive part of the museum and includes hands-on activities where visitors can learn about or test different construction techniques.

It starts with a walk through a partially collapsed classroom building from when Kuangfu Junior High School was located here. In addition to eerie classrooms with writing still on the chalkboard from Sept. 20, 1999, visitors can see concrete (in both senses of the word) examples of structural failure. The pillars here did not have enough rebar hoops and their ability to flex was restricted by partial walls, so they ended up bending, twisting and shattering in the middle, leaving their innards exposed. One of these pillars was later reinforced with the pillar expansion technique to illustrate how older buildings can be retrofitted for added stability.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

Inside the Earthquake Engineering Hall itself, there are activities and information panels that are simple enough to capture the attention of young children, but in-depth enough to satisfy any curious adult. The hands-on activities actually work, clearly demonstrating what they are supposed to, and the QR codes on the walls link to simple but informative videos that expand on the basic principles shown in the activities.

Crank an earthquake wheel and watch water trapped in the soil rise to the top as the little house without piles sinks. Shake building frames at different speeds and see how short and tall buildings respond. Make buildings with or without structural walls, and then see which ones topple first. These activities are quick and fun while demonstrating principles clearly enough for all ages to understand. More advanced seismic isolation and monitoring techniques using lead-rubber bearings and subtle shifts in the reflective properties of fiber optic cables are also explained here, for those with an appetite for something more technical.

MEMORIAL TO A DISASTER

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

In the third hall, there is an “Earthquake Experience Theater” where, for NT$30, visitors can sit on a shaking platform that simulates a strong earthquake, accompanied by animation and narration of the 921 Earthquake’s story playing on the surrounding screens. While this is rather entertaining, as are the hands-on activities in the previous gallery, the museum also does its best to serve as a somber memorial for the earthquake that claimed 2,456 lives and injured 10,718. The remainder of this gallery does an excellent job of telling the personal stories and the societal upheaval that resulted.

Along one hallway, there are reprints of news blurbs from the days after the quake. One can start on Sept. 21 and follow the story of the disaster response as it unfolded just by walking down the hall. This perspective, reflecting the dynamic and unpredictable nature of the event, is a refreshing change from the usual retrospective linear narrative of events found in museums and textbooks. Visitors who cannot read Mandarin can follow along thanks to high-quality English and Japanese translations printed right alongside the originals.

This third building is named the “Image Gallery” and does have a heavy focus on art. There are paintings by Lukang native Professor Vince Shih (施並錫), created after he witnessed the earthquake’s immediate aftermath in person. In another hallway, a display of breathtaking photographs captures the sorrow, the triumph and the awesome destruction of this disaster.

Photo: Tyler Cotteni

The most moving of all is the “Memories of the Families” exhibit, which, unfortunately, is one of the few areas in the museum that does not have English translations. Each picture captures one family, often in front of their ruined home, and is accompanied by a description of how the earthquake affected them personally. These personal touches humanize the disaster in a way that statistics or news reports alone cannot. One photo shows two sisters posing with their grandfather in front of a landslide as an excavator searches for their parents, who were never found. Then there is the family who were only sure where their apartment lay in the rubble after they discovered their small Buddha statue. Each is worth a read, so bringing a translation app or a local who can translate is highly recommended.

A SCHOOL SPLIT IN HALF

After the third gallery, it’s time to go for a walk outside on the grounds of the former junior high school for the climax of the tour. This is where the power of an uplifting faultline is in plain view and preserved for posterity. Two collapsed buildings and a damaged running track give visitors a perspective seldom seen anywhere else in the world.

Photo: Tyler Cotteni

The school’s three-story walkway completely collapsed during the quake, with the pillars all neatly folding the same way and the floors and ceilings falling straight down to create a concrete sandwich, now only two meters high. Pre-quake photos posted nearby show students standing atop this walkway and waving, oblivious to the tectonic stress building in the faultline under their feet.

Next to this is the heavily damaged north classroom building, which sat right on the faultline itself. The uplifted ground starts outside the school entrance, passes through the collapsed north classroom building, and continues on all the way across the running track into the first gallery. The lines of the running track, once arrow-straight and level, are now folded and twisted impossibly upward. This is where the effects of a powerful earthquake on the shape of the Earth itself are most visible and is a good place to end your tour, right back on the faultline where you started.

IF YOU GO

Photo: Tyler Cotteni

The museum is open from 9am to 5pm every day except Mondays. Tickets are NT$50, and free lockers are available. The facility is wheelchair accessible. Parking is available nearby for those who come by car. Alternatively, catch a bus in front of the Taichung railway station: either Bus 107 or 200 from Taiwan Blvd. to Kengkou Village (坑口), or Bus 50 from Chenggong Road to Guangfu New Village (光復新村) Traffic Circle. Walk 15 minutes east to the museum, at 192 Sinsheng Rd, Wufeng District, Taichung City (臺中市霧峰區新生路192號). Free guided tours are offered a few times a day starting around 9:30am but are in Chinese only.

From the last quarter of 2001, research shows that real housing prices nearly tripled (before a 2012 law to enforce housing price registration, researchers tracked a few large real estate firms to estimate housing price behavior). Incomes have not kept pace, though this has not yet led to defaults. Instead, an increasing chunk of household income goes to mortgage payments. This suggests that even if incomes grow, the mortgage squeeze will still make voters feel like their paychecks won’t stretch to cover expenses. The housing price rises in the last two decades are now driving higher rents. The rental market

July 21 to July 27 If the “Taiwan Independence Association” (TIA) incident had happened four years earlier, it probably wouldn’t have caused much of an uproar. But the arrest of four young suspected independence activists in the early hours of May 9, 1991, sparked outrage, with many denouncing it as a return to the White Terror — a time when anyone could be detained for suspected seditious activity. Not only had martial law been lifted in 1987, just days earlier on May 1, the government had abolished the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of National Mobilization for Suppression of the Communist

Hualien lawmaker Fu Kun-chi (傅?萁) is the prime target of the recall campaigns. They want to bring him and everything he represents crashing down. This is an existential test for Fu and a critical symbolic test for the campaigners. It is also a crucial test for both the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and a personal one for party Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫). Why is Fu such a lightning rod? LOCAL LORD At the dawn of the 2020s, Fu, running as an independent candidate, beat incumbent Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) lawmaker Hsiao Bi-khim (蕭美琴) and a KMT candidate to return to the legislature representing

Fifty-five years ago, a .25-caliber Beretta fired in the revolving door of New York’s Plaza Hotel set Taiwan on an unexpected path to democracy. As Chinese military incursions intensify today, a new documentary, When the Spring Rain Falls (春雨424), revisits that 1970 assassination attempt on then-vice premier Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國). Director Sylvia Feng (馮賢賢) raises the question Taiwan faces under existential threat: “How do we safeguard our fragile democracy and precious freedom?” ASSASSINATION After its retreat to Taiwan in 1949, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) regime under Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) imposed a ruthless military rule, crushing democratic aspirations and kidnapping dissidents from