Aug.12 to Aug.18

Doris Brougham (彭蒙惠) was tempted to leave Taiwan many times over the decades, from her mother’s death to a marriage proposal to a lucrative job offer in Vietnam when she struggled financially.

But it just never felt right. The Christian missionary and pioneering English-language educator believed that it was God’s plan for her to remain here, writes Lee Wen-ju (李文茹) in Brougham’s biography Love is a Lifetime of Persistence (愛是一生的堅持).

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

After making Taiwan her home for 73 years, Brougham died on Tuesday at the age of 98.

She once said, “When Taiwan withdrew from the UN, I was in Taiwan, during the 921 Earthquake, I was in Taiwan. I’m a Taiwanese, wherever I am, that’s where my heart is, Taiwan is my home.”

But despite this, Brougham remained on a work visa that required annual renewal until restrictions on permanent residency were relaxed in 2002. She was finally granted citizenship last May.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

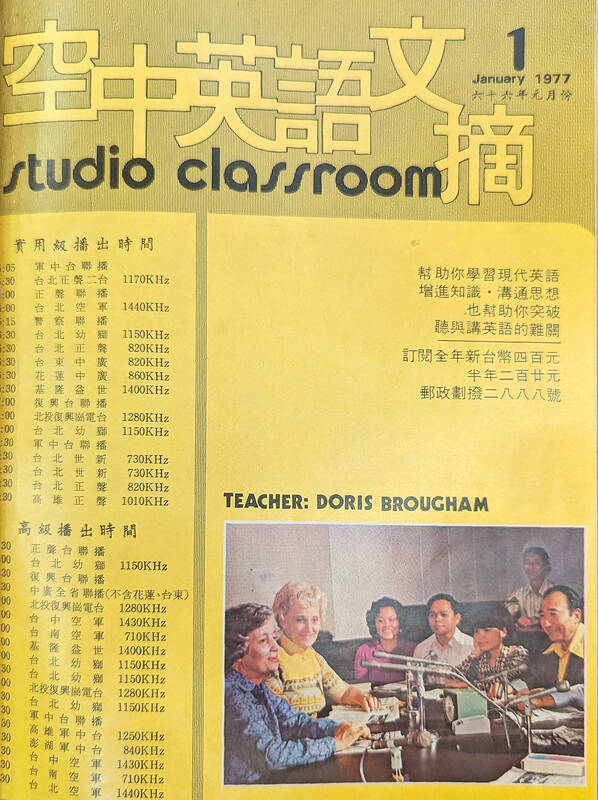

Brougham’s Studio Classroom (空中英語教室) TV / radio programs and magazines, launched in 1963, continue to inspire generations of Taiwanese to learn English in a fun, conversational way.

WARTIME CHINA

Brougham never planned to come to Taiwan; in fact she had barely even heard of China when she first made up her mind as a 12 year old to go evangelize there. Born and raised in the Seattle area in 1936 to a family of modest means with nine children during the Great Depression, Brougham’s opportunities to travel were limited.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

While she was attending a Bible summer camp on a scholarship, she heard one of the pastors Andrew Gih (許志文) speak about his homeland and the dangers that Western missionaries faced there. Brougham was especially moved by the story of John and Betty Stam, who were executed by Chinese communists in 1934.

“Who is willing to go to China?” Gih asked after a study session, and Brougham raised her hand. Nobody took her seriously, but she never forgot about it. Years later, the talented horn player gave up a full scholarship to attend the Eastman School of Music in New York, instead enrolling in the Simpson Bible Institute to prepare for missionary work.

Brougham was so determined to go to China that whoever wanted to date her had to have the same plans. While studying Mandarin and Far Eastern Studies at Washington University in 1947, she found a kindred spirit in a man named Jim.

Photo: CNA

However, it just wasn’t a good time to travel there; World War II had just ended and the Chinese Civil War continued ravaging the country. It didn’t matter, however, and Brougham arrived in Shanghai in November 1948 as a member of the Evangelical Alliance Mission.

The situation deteriorated quickly upon her arrival, and the group fled west to Chongqing, Chengdu and finally Lanzhou, where they caught the last plane to Hong Kong in August 1949 just as the People’s Liberation Army descended upon the airport.

BROADCASTING GOD’S WORD

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

Brougham spent about a year in the British colony, working with refugees and becoming the only American and female performer in the Hong Kong Orchestra. Rumors flew that the communists were advancing, and the mission planned to relocate its Asia operations to Japan.

Brougham’s Mandarin had greatly improved by then, and she decided that unless she was sent back to the US, she wanted to stay with the Chinese. In December 1950, she headed to Formosa, where there were also Chinese speakers — but ironically, she spent her first seven years in a part of Hualien where locals spoke only Japanese and indigenous languages.

Jim never made it to China, and Brougham never responded to his last letter. Her father and mother both died during this time, but she resisted the urge to return to Seattle. Most missionaries arriving opted for the more populated east coast, but Brougham looked at the map and chose Hualien, where she began teaching at the Yushan Theological College and Seminary. The children learned Mandarin quickly at school, and she was able to communicate through them.

Brougham wanted to spread Christianity to more Taiwanese, and thought radio would be an effective medium. She wrote to the Broadcasting Corporation of China (中廣), who to her surprise immediately agreed to give her a one-hour weekly program.

Recorded with makeshift equipment in her flat, the show included songs, skits, sermons and music. Sometimes, the guests and staff were too busy to show up, and Brougham ended up playing an hour of trumpet; she jokingly called these sessions solo recitals.

The show was well received, and her media career grew rapidly. Around this time, she fell in love with a doctor at the Mennonite Christian Hospital, who asked her to marry him and move back to the US. Brougham wanted a family, but she just could not leave Taiwan. She turned him down, saying she already made a promise to God.

TEACHING ENGLISH

On a fundraising trip back home, Brougham ran into high school friend Leland Haggerty, who was married with four kids and a nice job. Haggerty showed interest in helping out with the venture, but Brougham did not expect him to move to Taiwan with his entire family.

The nation was about to enter the television age with the launch of Taiwan Television (台視, TTV) in 1963. Brougham saw the potential of the new tech and relocated to Taipei so she could work with the station, selling valuable mementos such as her father’s saxophone to fund the move. The 16 staff pooled their resources to make it work, even taking on odd jobs such as cleaning houses and tutoring. Soon they established Overseas Radio and Television (ORTV).

The programs were popular, but money remained tight. Brougham received a high-paying offer from the US government to work with Chinese in Vietnam that could ease their worries, but she felt an inexplicable unease and refused the offer. Instead, she headed to the US and Canada to fundraise.

In 1963, the Ministry of Education commissioned Fu Hsing Broadcasting Station (復興) to produce an English learning program. Brougham saw how Taiwanese struggled with English at the various international conferences she attended, and was happy to help.

On Aug 1, Studio Classroom hit the airwaves. Brougham eschewed the standard “this is a pen” teaching format, instead sharing interesting articles from American magazines and explaining the contents in a casual, conversational manner. It was a huge hit, and per listener request they began publishing a two-page supplement to the show. This grew into a full magazine by 1974.

Chinese writer and translator Lin Yu-tang (林語堂) became a fan of the show after moving to Taiwan in 1966, the two became good friends. He helped further boost the show’s listenership.

Brougham also hosted the “Heavenly Melody” musical program on TTV, the only religious show at that time which drew the ire of other groups. This led to the formation of Taiwan’s first full-time Christian choir that performed original tunes and toured overseas.

Although her goal was still to evangelize, Studio English was Brougham’s best-known venture, not just teaching the language but exposing locals to many new concepts and ideas. Brougham also taught English to China Airlines flight attendants for many years and was personally commissioned by president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) to help top government officials with the language. She was noted for her ability to get these powerful individuals to relax their pride and have fun in class.

Brougham received countless awards for her contribution, including the Order of Brilliant Star, Taiwan’s highest non-military honor.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.