Aug. 5 to Aug. 11

A representative from the Chang-Liao-Chien (張廖簡) clan association will open the gate to the underworld at 2pm today. The unique ritual, where the participant takes an actual key to unlock a metal door at Keelung’s Laodagong Temple (老大公廟), marks the beginning of Ghost Month, when spirits are allowed to visit the world of the living. The hungry souls won’t need to go far for their first feast as the temple welcomes them with ample offerings.

Keelung’s Midsummer Ghost Festival celebrates its 170th anniversary this year, first starting as a way to unite warring local factions and transmute the souls of those who perished in the bloody conflicts. Today, it is considered the nation’s largest of its kind, with events taking place throughout the seventh month of the lunar calendar.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The door at Laodagong Temple isn’t closed until the first day of the eighth month — allowing the ghosts one more day than usually allotted to roam the human realm.

BLOOD WARS

Most sources agree that the festival has its origins in the longstanding conflict between Han Taiwanese of Zhangzhou and Quanzhou (both in China’s Fujian Province) origins, which intensified in the 1850s. The Keelung City Annals (基隆市志) state that the Zhangzhou faction occupied today’s downtown Keelung, while the Quanzhou side resided in Nuannuan District (暖暖). Their territories met at Fangding (魴頂), near today’s Badu Railway Station.

Photo courtesy of Keelung City Government

The two groups fought frequently over missing livestock, land and basically any petty argument. The common version states that a particular nasty incident in 1853 led to the death of 108 people, mostly from the Zhangzhou side, who planned to invade Quanzhou land but were instead ambushed. The Zhangzhou faction vowed to exact revenge, but concerned locals, weary of the unrest, convinced them to transmute the souls of the victims first by burying them in a mass grave and building the Laodagong Temple to honor them. Accounts of the incident vary and different years are given, but the gist is the same.

Historian Wu Huey-fang (吳蕙芳) writes in Geopolitical conflicts and the resolution of bloodlines (地緣衝突與血緣化解) that it’s “highly possible” that Lin Ben-yuan (林本源) of the Banciao Lin family served as the chief mediator between the two groups. The powerful Lins were of Zhangzhou extraction, and owned much land in Keelung.

It’s unclear how they came to this agreement, but starting in 1855, one of 11 local clan associations from both sides took turns conducting the temple’s Ghost Month festivities.

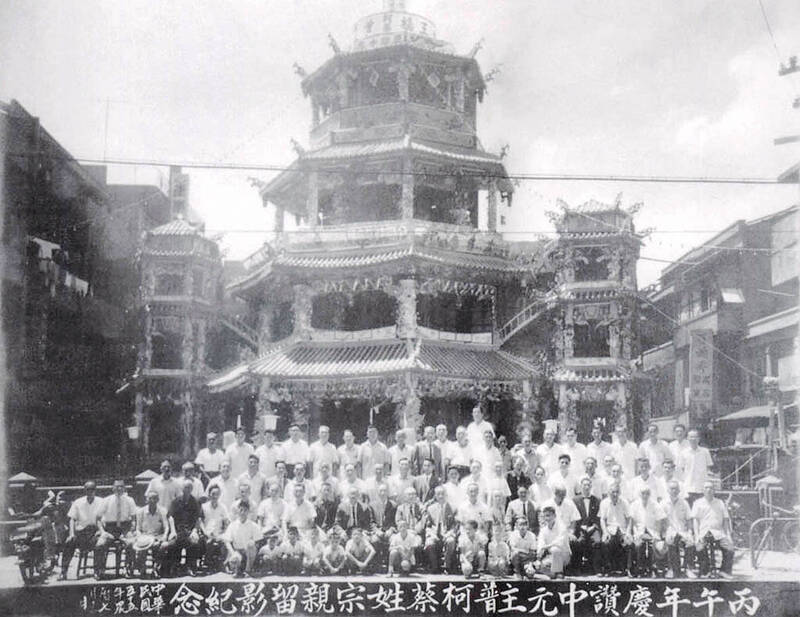

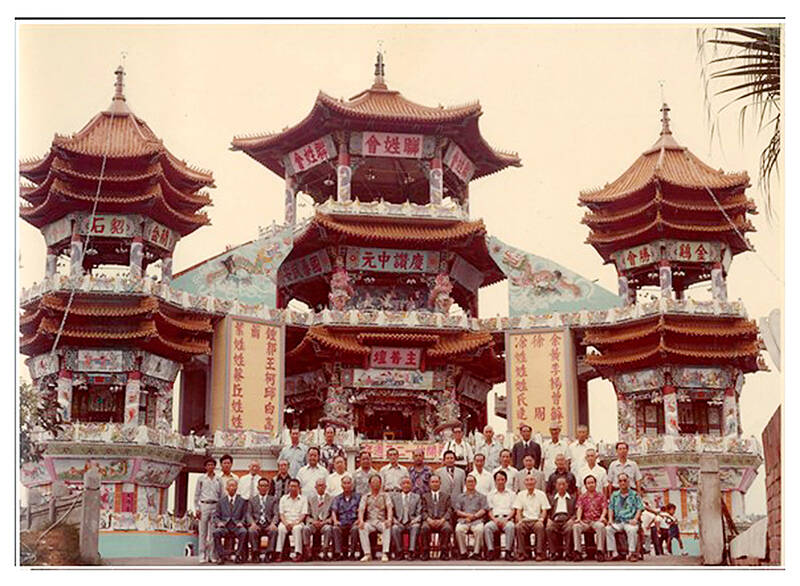

Photo courtesy of Keelung City Government

While official sources today state that the two sides made a pact to compete in religious performances during the festivities rather than perpetuate the endless cycle of violence, Wu believes that this wasn’t the case at first. Deadly clashes between the two sides continued until the early 1860s, and the Ghost Month festivities were held to care for the dead spirits and to bring peace of mind to the survivors.

HOSTING PRIVILEGES

The clans each drew lots of hosting order, with the Chang-Liao-Chien association going first, and the Hsu clan (許) last.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Cultural Memory Bank

Participants weren’t limited to families from Keelung proper, but also surrounding areas of Jinbaoli (金包里, today’s Jinshan, 金山, and Wanli, 萬里 districts), Shiding (石碇, today’s Shiding, Ruifang, 瑞芳, Cidu, 七堵, and Nuannuan districts) and Sandiaoling (三貂嶺, today’s Pingsi, 平溪, Shuangsi, 雙溪, and Gongliao, 貢寮 districts).

Out of the several oldest families to settle in the area, only the Ho (何) were included in the rotation, Wu writes. Instead, the list was made up those who wielded influence in local society and commerce. The Ho, Lai (賴) and Hsu (許) owned the bulk of the land in downtown Keelung, while Wu (吳), Chang (張), Hsieh (謝), Chen (陳) and Chiang (江) family members feature in records detailing the founding, construction and expansion of the area’s major temples.

The clans took the role very seriously and began preparations months prior; in 1914 the Hsieh’s rallied nearly 100 of households to discuss the festivities, putting on a spectacular water lantern display that year with a dragon made of hundreds of state-of-the-art lights, snaking its way down the river.

Photo courtesy of Keelung City Government

Wu notes that hosting the ceremonies was not the only way for families to display their power; the non-hosts poured their resources on elaborate parade performances and lantern shows, which became increasingly lavish over time as they tried to outshine each other.

“The clan associations racked their brains and made every effort to outshine the previous host, whether it be building the main altar, parade performances or animal sacrifices,” she writes.

Tens of thousands crowded into the streets to see the spectacles, often paralyzing traffic. As the violence eventually died down, the festivities became the main way for rivals to compete.

Not all families retained their clout as time went on. Wu writes thant by the 1930s, the Lee (李), Huang (黃) and Kuo (郭) had risen to prominence while the Hsieh, Chiang, Lai and Hsu had declined. In 1931, feeling the burden of hosting the festivities, former mayor Hsu Tsu-sang (許梓桑) invited other families to join him, but none accepted the offer.

FANCY ALTARS

The festival kept expanding and came to include four altars, with the rotating clan in charge of the main one. Prominent families not included in the rotation would sometimes take charge of a lesser altar.

A new main altar was constructed each year, each more flamboyant than the previous one. By the 1920s, it was standard practice to build three three-story structures connected with arched bridges and traditional landscaping decorations.

In 1929, a permanent main altar adorned with 800 electrical lights, designed with the approval of each association, was built to save energy and resources. It also served as a concert hall during the rest of the year.

The festivities were significantly curtailed with the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937. The following year, only a simple ceremony to transmute the souls of hungry ghosts and dead soldiers was held, with the remaining events canceled.

The event resumed after the war but only with one altar, never returning to its prior scale. Damaged by US airstrikes in 1945, the main altar was rebuilt in 1956. Hosting families still liked to attach their own additions to the structure, even raising the main tower to four stories in 1966.

Inaugurated in 1964, the MacArthur Expressway passed right by the main altar, leading to major traffic jams during the festivities. As a result, the government rebuilt the altar in Zhongzheng Park in 1974.

Meanwhile, in 1947, a number of clans that helped out regularly at the side altars banded together to form a joint association that became the 12th rotating host. The aforementioned Lee, Huang and Kuo each formed their own associations in 1981, completing the current roster of 15.

The main events this year will take place from Aug. 14 to Aug. 18. For more details (Chinese only), visit: www.rs-event.com.tw/2024/2024kmsgf/index.html.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Next week, candidates will officially register to run for chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). By the end of Friday, we will know who has registered for the Oct. 18 election. The number of declared candidates has been fluctuating daily. Some candidates registering may be disqualified, so the final list may be in flux for weeks. The list of likely candidates ranges from deep blue to deeper blue to deepest blue, bordering on red (pro-Chinese Communist Party, CCP). Unless current Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) can be convinced to run for re-election, the party looks likely to shift towards more hardline

Sept. 15 to Sept. 21 A Bhutanese princess caught at Taoyuan Airport with 22 rhino horns — worth about NT$31 million today — might have been just another curious front-page story. But the Sept. 17, 1993 incident came at a sensitive moment. Taiwan, dubbed “Die-wan” by the British conservationist group Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), was under international fire for being a major hub for rhino horn. Just 10 days earlier, US secretary of the interior Bruce Babbitt had recommended sanctions against Taiwan for its “failure to end its participation in rhinoceros horn trade.” Even though Taiwan had restricted imports since 1985 and enacted

Enter the Dragon 13 will bring Taiwan’s first taste of Dirty Boxing Sunday at Taipei Gymnasium, one highlight of a mixed-rules card blending new formats with traditional MMA. The undercard starts at 10:30am, with the main card beginning at 4pm. Tickets are NT$1,200. Dirty Boxing is a US-born ruleset popularized by fighters Mike Perry and Jon Jones as an alternative to boxing. The format has gained traction overseas, with its inaugural championship streamed free to millions on YouTube, Facebook and Instagram. Taiwan’s version allows punches and elbows with clinch striking, but bans kicks, knees and takedowns. The rules are stricter than the

Nearly three decades of archaeological finds in Gaza were hurriedly evacuated Thursday from a Gaza City building threatened by an Israeli strike, said an official in charge of the antiquities. “This was a high-risk operation, carried out in an extremely dangerous context for everyone involved — a real last-minute rescue,” said Olivier Poquillon, director of the French Biblical and Archaeological School of Jerusalem (EBAF), whose storehouse housed the relics. On Wednesday morning, Israeli authorities ordered EBAF — one of the oldest academic institutions in the region — to evacuate its archaeological storehouse located on the ground floor of a residential tower in