April 8 to April 15

Westerners in the late 1800s had such a poor opinion of Taiwan that they were often shocked that Patrick Manson managed to spend five years here.

“Good heavens, how could you exist for so long in an outlandish hole? You could have no society there, no amusements, a blazing sun and murderous savages,” they would say, and when Manson tried to explain that he actually liked living there, they pitied him, doubting his “truthfulness or sanity.”

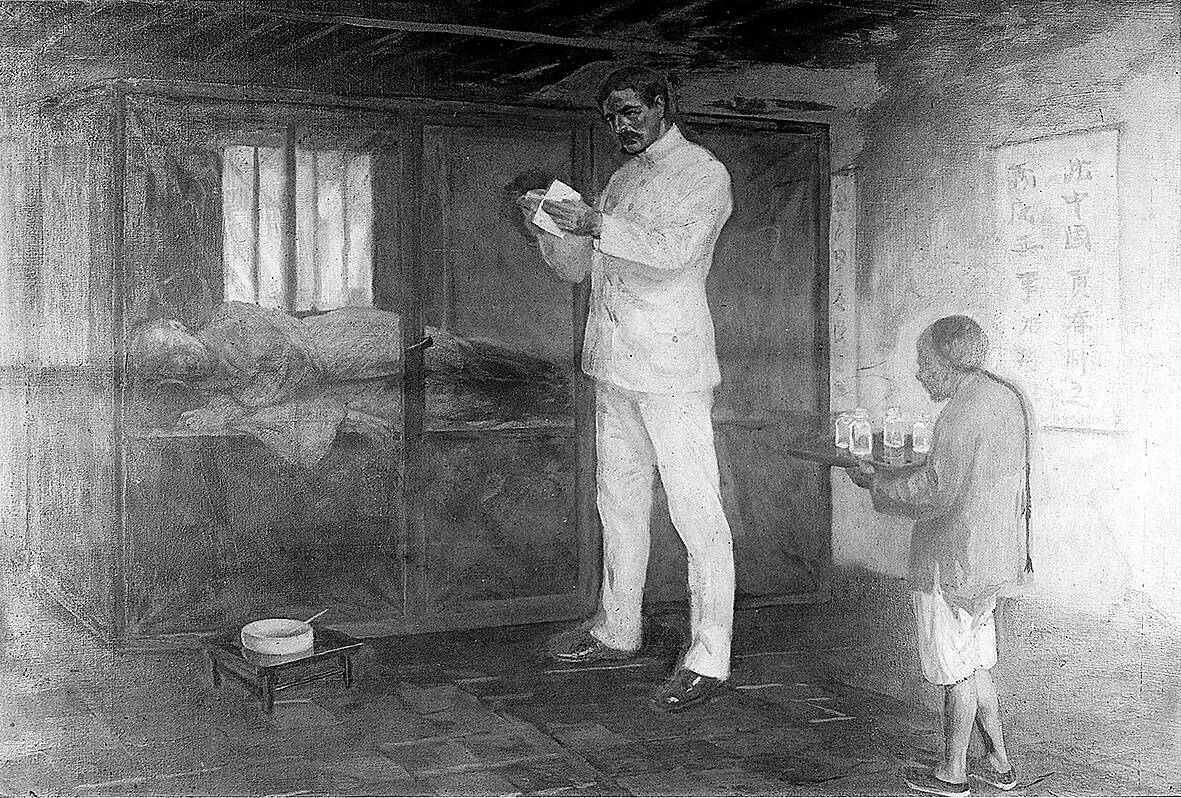

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“If a man derives his pleasure from billiards, good dinners, small talk, a game at whist and the latest novel — he had better keep away from Formosa,” the former medical officer for the customs office in Takao (today’s Kaohsiung) writes in the 1873 article “A gossip about Formosa” published in the China Review. “But if his taste is for lovely scenery, a roving life, a clear sky, kindly people, a little adventure and plenty of shooting, let him try our island.”

Arriving in 1866 at the age of 21, Taiwan was Manson’s first stop in his career. It was here that he honed his medical and research skills with minimal supervision and equipment, and developed an interest in studying tropical diseases such as malaria, leprosy and elephantiasis.

Years later, Manson became the first person to demonstrate that mosquitoes can transmit pathogens through studying the filaria sanguinis-hominis parasite, and posited that malaria is also spread via the insect, which today we know to be true. After leaving Taiwan in 1871, Manson concluded his career in Xiamen and Hong Kong and at the Tropical Medicine Conference in 1913, he was honored as the “father of tropical medicine.”

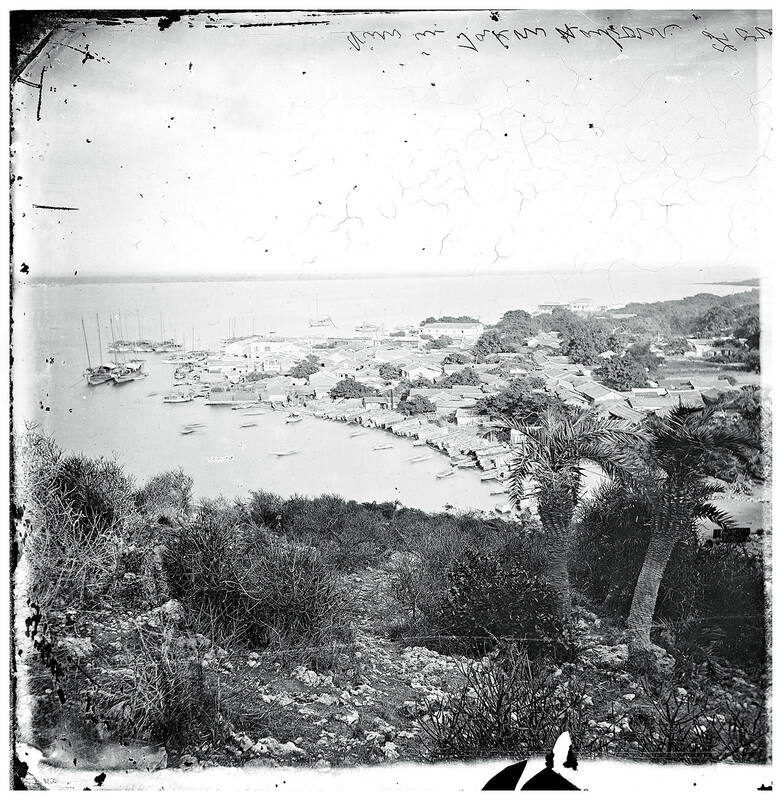

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

He died on April 9, 1922. A plaque in his hometown of Aberdeen states that he is the “first to show that insects carry disease.”

WESTERN DOCTORS ARRIVE

In 1858, the Treaty of Tianjin forced the Qing Dynasty to open up Kaohsiung, among other ports in Taiwan, for trade with the West. The British established a consulate in Tamsui in 1861, and moved it to Kaohsiung in 1864. This also led to the arrival of Western physicians, beginning in 1865 with James Maxwell — who was also the first Presbyterian missionary to Taiwan.

Photo courtesy of Internet Archive

Manson was born in 1844 near Aberdeen, Scotland, and obtained his doctor of medicine in 1865 from the University of Aberdeen. Armed with just seven months of experience as an assistant medical officer in a mental asylum, Manson boarded a ship for Taiwan.

Chu Nai-shin (朱迺欣) writes in a Taiwan Medical Journal (台灣醫界) article that there was a lack of domestic job prospects then for Scottish medical graduates compared to their British counterparts, and many found work overseas either with the military or with the colonial medical service. Manson had also accrued significant student debt, and was in dire need of a job to pay it off.

Phillip Manson-Bahr writes in The Life and Work of Sir Patrick Manson that Manson was “soon tired of mental work within the confines of an asylum, but his adventurous spirit found an opening when, through the interest of his elder brother, then in Shanghai, he obtained the appointment of a medical officer for Formosa.”

Photo courtesy of Wellcome Collection

The position was established by customs service inspector-general Robert Hart, who, according to Manson-Bahr, “recruited most of his medical officers from Scottish schools.” Manson’s job was to inspect the arriving ships for diseases, supervise the sanitation of the port and serve the tiny European community of about 16 people. Medical services were strongly needed in tropical areas of British interest, which were dubbed the “white man’s grave” as countless succumbed to various diseases.

Hart also instructed Manson to regularly report on the climate, local conditions and illnesses that affected locals, and his earliest studies were published in the custom service’s Medical Reports.

EXCURSIONS INLAND

Manson also regularly helped out at Maxwell’s clinic, eventually taking it over in 1869 when the missionary moved to Tainan.

Kelvin KW To and Kwok-Yung Yuen write in an Emerging Microbes and Infections article that at the clinic, Manson was “exposed to a wide variety of illnesses from elephantiasis to leprosy for his postgraduate training without any supervision,” and that “his only research tool was a combination of clinical skill, hand lens and good record keeping.”

The port wasn’t particularly busy during those days, and Manson spent his free time riding horses, hunting, gardening, swimming and fishing. He visited indigenous villages to observe the customs and endemic diseases there.

He describes some of his excursions inland in the “gossip” article, going into detail about the scenery and culture he observed. Particularly interesting is his writing on the plight of the indigenous Pingpu of the plains, where he uses “Chinaman” to refer to Taiwanese who claim ancestry from Fujian Province in China, while the Hakka are a separate group.

“Strange how the Chinaman has succeeded in completely ousting the original dwellers in his land, robbing him of his fat plains and pinning him into a narrow strip of stony, unfruitful ground at the foot of the hills, the bear-hunting savage on one side of him, the thieving Hakka on the other and starvation and want in his house,” he writes. “The Hakka preys upon him as soon as he has anything to steal, and the Chinaman on both.”

“And so we feel, that not many years hence, the [Pingpu] of Formosa will be numbered among the extinct races, without a relic to mark their former existence, not a stone of their own raising, only a short notice in some ancient Dutch book … their language is dead already, only once have we met anyone who speaks it.”

Curiously, he notes that the Pingpu had more of an affinity to Westerners since they were both called fan (番, savages or foreigners) by the Han Taiwanese.

THE MANSON LEGACY

It’s not exactly clear why Manson left Taiwan in 1871, but it might have something to do with the Mudan Incident (牡丹社事件), which happened the same year. The killing of 54 shipwrecked Ryukuan sailors who had accidentally wandered into indigenous territory brought Japan into contention with the Qing Dynasty over Taiwan, and some sources say Manson had angered the Japanese by procuring horses for Qing forces. Other accounts say that he became involved in a dispute between Han Taiwanese factions. In any event, the British Consular strongly advised him to leave for Xiamen.

His younger brother David Manson took over his duties after his departure. David stayed in Taiwan for four years before also heading to China, where he died from disease in 1878. To commemorate his service, then-customs medical officer William Wykeham Myers collected donations and founded the David Manson Memorial Hospital in today’s Cijin District (旗津) that same year. It consisted of two buildings and the facilities were consider}ed quite advanced for its time.

The hospital established Taiwan’s first Western medical school in 1884, which adhered to Scottish educational standards. It continued to operate after the Qing ceded Taiwan to Japan in 1895, but ceased to provide medical services in 1910. It was razed in 1937.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand