Taiwan’s post-World War II architecture, “practical, cheap and temporary,” not to mention “rather forgettable.” This was a characterization recently given by Taiwan-based historian John Ross on his Formosa Files podcast. Yet the 1960s and 1970s were, in fact, the period of Taiwan’s foundational building boom, which, to a great extent, defined the look of Taiwan’s cities, determining the way denizens live today.

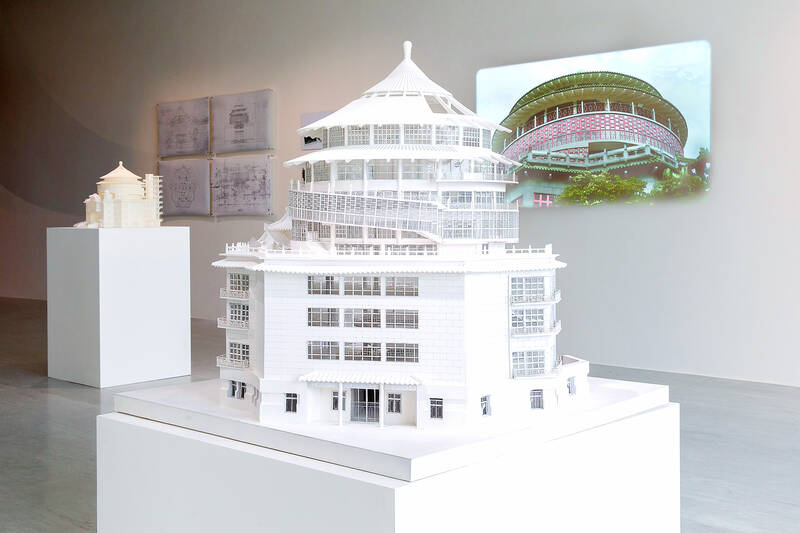

During this period, functionalist concrete blocks and Chinese nostalgia gave way to new interpretations of modernism, large planned communities and high-rise skyscrapers. It is currently the subject of a new exhibition at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum, Modern Life: Taiwan Architecture 1949-1983, which opened last Saturday and runs until Jun 30.

Though the buildings displayed through photographs, blueprints, artist renderings and models are classed as “Taiwanese,” they were actually designed by a generation of Mainlander architects who came over with Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) and his retreating Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) armies in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Just as with the bureaucracy of Taiwan’s Republic of China (ROC) government nearly all of the architects and urban planners were born in China.

Photo courtesy of TFAM

CHINESE DESIGNS

When these architects got to work in the late 1940s, their first task was the “de-Japanization” and “re-Sinicization” of Taiwan’s urban landscapes. A new Construction Bureau set up under the central government’s Civil Affairs Department directed its energies to creating new homes for a government bureaucracy that had been migrating in tow with the KMT military since Japan pushed them out of the ROC capital of Nanjing in 1937. Most were arriving from Chiang’s final wartime headquarters of Chongqing, which in 1949, fell to Mao Zedong’s (毛澤東) communists.

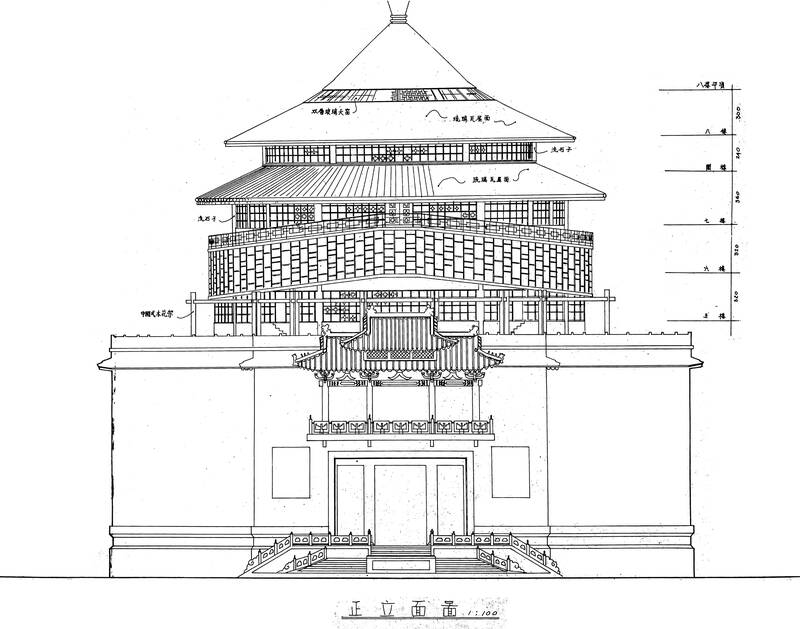

One of the earliest buildings of this era of retreat was the Taiwan Bank Kaohsiung Branch, completed in 1947. A three-story reinforced concrete block capped with a green-tiled Chinese roof, the building is emblematic of a newly imported “Chinese retro” trend, which would go on to produce many of Taiwan’s major landmarks, from the first iteration of the Grand Hotel in 1953 to the National Concert Hall and National Theater in 1987 — a period which coincided almost perfectly with Taiwan’s Martial Law era.

Photo courtesy of TFAM

The style has also been called “neo-imperial” or “palace-style” architecture as it draws chiefly from the imperial palace designs of the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644 —1911) dynasties, buildings that equated symmetry in building plan and facade design with architectural harmony. Exteriors are generally divided into a three-part, vertical composition of block-like foundations, bodies of imposing solid walls, and peaked roofs of glazed tiles with curved up eaves. Entrance ways and overhanging roofs are often supported by vermillion columns connected to the superstructure by a system of rectilinear brackets.

But while pre-modern Chinese palaces were mainly built of stone and wood, and thus limited in size, Taiwan’s retro Chinese buildings of the 1950s to the 1980s using reinforced concrete and steel frame construction could achieve unprecedented scale.

One prominent example is architect Yang Cho-cheng’s (陽卓成) design of the second phase of Taipei’s Grand Hotel, which still stands today as a major landmark in Taipei’s Zhongshan District (中山區). Inspired by the Hall of Supreme Harmony in Beijing’s Forbidden City, it became Taiwan’s tallest building upon its completion in 1973, standing 14 stories and 87 meters tall, a status it retained until it was surpassed in 1981 by the First Commercial Bank Building on Taipei’s Dunhua South Road, which hearkened a new wave of skyscrapers.

Photo: David Frazier

In Taiwan’s “Chinese retro” architecture, exterior design elements became largely ornamental and symbolic, intended to broadcast a message to both Taiwan’s citizens and the world that the government in Taipei was in fact the true and rightful government of China. The interiors meanwhile were, meanwhile, modern and functional.

Post-war construction also saw a major influence from US aid programs, which supported Taiwan’s infrastructure development from 1951 to 1965. Virtually every department in Taiwan’s government interacted with US aid agencies, and funding guidelines dictated the adoption of American standards, including detailed schematics and English labeling on all architectural diagrams.

US architectural firms like Adrian Wilson and Associates, which constructed buildings for the US military around Taiwan, also influenced designs for Taiwan’s new civilian architecture. These new imported styles were fully modernist and highly functional, applying cantilevered roofs, curtain walls, and American rationalist concepts like “form follows function.” The Cheng Kung University Library (1959) was built as a Mies van der Roh-style glass rectangle, while the National Taiwan University Agricultural Exhibition Hall (1963) used a concrete beam-columns structure and walls coated in cylindrical tiles.

Photo: David Frazier

Another key, if indirect, influence on Taiwan’s incipient modernism was Walter Gropius, who influenced a trio of highly influential ROC architects, all born in China and educated in the US. The German-born Gropius was one of the founders of the Bauhaus movement in 1920s Berlin, then went on in 1945 to continue to develop modernist ideas in the US through a group called The Architects Collaborative. His ROC acolytes included Chen Chi-kwan (陳其寬), an alumnus of The Architects Collaborative and designer of Taipei Songshan Airport (1971); Chang Chao-kang (張肇康), who studied under Gropius at Harvard and collaborated with I.M. Pei (貝聿銘) in the design of Tunghai University in Taichung; and Wang Da-hong (王大閎), also Gropius’s student at Harvard, who designed Taipei’s Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall (1972).

This infusion of Western international style into Chinese tradition is described by exhibition curators as “Chinese Modern” that is “modern architecture with a distinctly Chinese character.”

Wang’s Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall, for example, still took cues from neo-imperial architecture as a symmetrically planned palace-style landmark. But at the same time, Wang streamlined the building’s lines and dispensed with ornamental motifs in favor of minimalist forms. The rippling texture of traditionally tiled roofs was replaced, for example, with expansive, flat surfaces.

Photo: David Frazier

Following on the heels of the US Aid-influenced buildings, Taiwan’s own brand of functional modernity began to proliferate in what some have disparaged as “toilet architecture,” ubiquitous concrete apartment buildings with tile exteriors. From the mid-1950s, vertical living in such four and five-story apartment buildings, now with indoor kitchens and plumbing became standard.

METROPOLITAN TAIWAN

The 1960s then saw Taiwan’s first public housing developments, department stores and planned neighborhoods. The latter included Taipei’s Minsheng Community (1964), which was modeled on Brooklyn-style neighborhoods of townhouses, and Sindian’s Garden City (花園新城)(1968), a subdivision of vaguely Frank Lloyd Wright-inspired concrete houses embedded in a mountainside jungle.

Photo: David Frazier

High-rise commercial office buildings and apartments only began to appear from the mid-1970s, especially on Taipei’s Dunhua South Road. Beginning in the 1980s, high-rises began to define the Taipei skyline.

All these trends accompanied a rush of urbanization, in which the nation’s city-living population exploded from 33 percent in 1956 to 78 percent in 2000.

The story of this seminal era is approached here via a heroic model of history, in which historical movements are defined by show-piece buildings and their famous architects. It’s a bit unfortunate, as much more could have been done to relate this formative building boom to the society that grew up along with it. No mention is made, for example, of the military villages that were a major part of urban landscapes in the 1950s and 1960s, nor the building codes that effectively standardized most building heights at five or 14 stories.

Curators also fall prey to the common Taiwanese foible of an inwardly looking myopia, or an inability to think beyond the confines of this small island. In describing an era when globalized style became the rule, the approach seems rather wanting. Postmodernism, for example, emerged as a major international architectural trend from the 1970s and could have easily been applied to ideas of “retro Chinese” or “Chinese modern” but is never mentioned. Other international trends are only quickly glossed over, and though a significant proportion of Taiwan’s architects continue to be educated internationally, the curators have assumed a uniquely Taiwanese trajectory of historical development.

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not