In King Lear, confronted with the figure of his cruelly blinded father, Edgar wonders whether matters are as bad as they imaginably could be. He concludes, however, that “the worst is not/So long as we can say “This is the worst.”’ The very fact that he has language, and the capacity for judgment, is itself proof that he has more to lose. Edgar’s words, in this most archaic of Shakespeare’s plays, feel horribly prophetic of the slaughter bench of modern history, as if the events of the 20th century were designed to test them. Is this the worst of which human beings are capable? Is this? Is this?

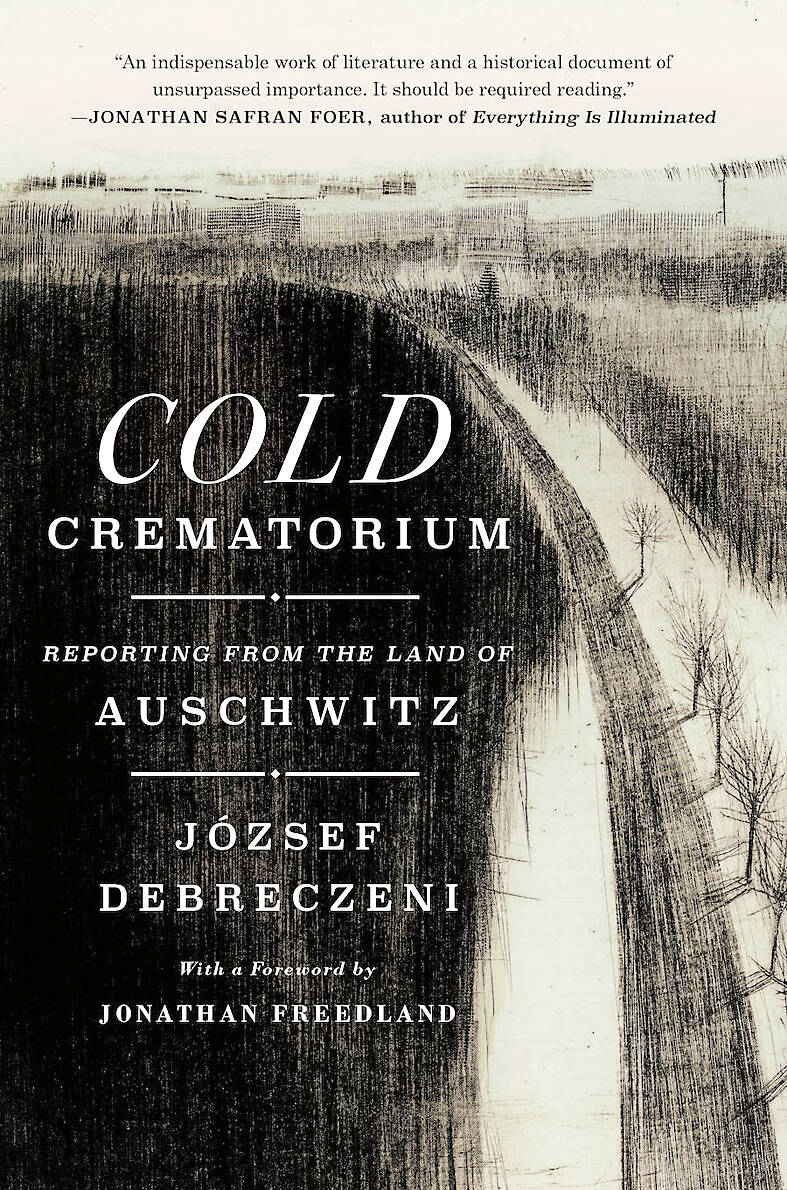

Jozsef Debreczeni’s memoir of the Nazi death camps, translated into English from Hungarian for the first time, frequently echoes Edgar’s claim. After being moved from “the capital of the Great Land of Auschwitz” to one of the networks of sub-camps, Eule, he discovers that he is to be moved again: “Surely I couldn’t end up in a place much worse, I thought — and how tragically wrong I was.”

By the end of his remarkable set of observational writings, the word “worse” has lost all meaning; comparing the depths of human experiences of depravity and suffering feels obscene in itself. Is typhoid worse than starvation? Is being crushed to death while mining a subterranean tunnel worse than wasting away in a pool of one’s own filth?

By the end of his remarkable set of observational writings, the word “worse” has lost all meaning

Debreczeni, an eminent journalist, thwarts any such comparisons by allowing the events that unfold to hover before the reader in the astonishing equipoise of his prose. In an excruciating moment for which the phrase “gallows humor” seems entirely inadequate, he tells us that the doctors’ nightly cry — “Report the dead!” — was responded to by “the more jocular among us” with “Report if you’re dead!”

Debreczeni’s account manages to make something of this unthinkable jocularity, to report the dead and to report his own life-in-death. He captures detail after harrowing detail. The old carpenter, Mr Mandel, an erstwhile chain-smoker whose hands still “moved mechanically, as if holding a cigarette” in the cattle car en route to Auschwitz. The former Czech army officer, Feldmann, who held “seance-like gatherings,” formulating detailed and futile plans for escape.

The spasm of generosity in which those soon to be transported to a new and unknown fate are given meagre gifts, a cigarette stub and a chunk of cabbage, by those who are left behind for the time being: “In the minds of those staying behind, this imperative throbs away: We’ve got to give, to give something.”

If this suggests residual humanity, there are in this coruscating bolt of truth none of the implausibilities and glib moral take-homes that have plagued and devalued Holocaust fictions, from Life Is Beautiful to The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas.

Debreczeni’s book makes spectacularly clear the difficult but necessary double demand of the Holocaust and its memorialization: what we might call the demands of the universal and the particular, or the general and the specific. To do its memory any kind of justice must mean to proclaim never again, for anyone: to decry and oppose all acts of mass violence. But the urgency of deriving this general imperative must not mean rushing too quickly past the particulars of what the Nazis and their enablers perpetrated; past its industrialized scale and mechanisms, its bureaucratized intricacies, its sheer massiveness and the massiveness of each life flayed, reduced, and destroyed.

Only through the difficult act of keeping both the general imperative and the specific example in mind at once can we hope to answer Debreczeni’s anguished call into the void on his first night at Dornhau: “Come here, you visionaries who create with pen, chalk, stone, or paintbrush; all of you who’ve ever sought to conjure up the grimace of suffering and death; prophets of the danse macabre, engravers of terror, scribes of hells — come here!”

President William Lai (賴清德) yesterday delivered an address marking the first anniversary of his presidency. In the speech, Lai affirmed Taiwan’s global role in technology, trade and security. He announced economic and national security initiatives, and emphasized democratic values and cross-party cooperation. The following is the full text of his speech: Yesterday, outside of Beida Elementary School in New Taipei City’s Sanxia District (三峽), there was a major traffic accident that, sadly, claimed several lives and resulted in multiple injuries. The Executive Yuan immediately formed a task force, and last night I personally visited the victims in hospital. Central government agencies and the

Australia’s ABC last week published a piece on the recall campaign. The article emphasized the divisions in Taiwanese society and blamed the recall for worsening them. It quotes a supporter of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) as saying “I’m 43 years old, born and raised here, and I’ve never seen the country this divided in my entire life.” Apparently, as an adult, she slept through the post-election violence in 2000 and 2004 by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), the veiled coup threats by the military when Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) became president, the 2006 Red Shirt protests against him ginned up by

As with most of northern Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) settlements, the village of Arunothai was only given a Thai name once the Thai government began in the 1970s to assert control over the border region and initiate a decades-long process of political integration. The village’s original name, bestowed by its Yunnanese founders when they first settled the valley in the late 1960s, was a Chinese name, Dagudi (大谷地), which literally translates as “a place for threshing rice.” At that time, these village founders did not know how permanent their settlement would be. Most of Arunothai’s first generation were soldiers

Among Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) villages, a certain rivalry exists between Arunothai, the largest of these villages, and Mae Salong, which is currently the most prosperous. Historically, the rivalry stems from a split in KMT military factions in the early 1960s, which divided command and opium territories after Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) cut off open support in 1961 due to international pressure (see part two, “The KMT opium lords of the Golden Triangle,” on May 20). But today this rivalry manifests as a different kind of split, with Arunothai leading a pro-China faction and Mae Salong staunchly aligned to Taiwan.