George Orwell was in his mid-40s, enjoying the peak of his fame after the publication of Animal Farm. Yet his mood was low after the death of his wife, Eileen. He was in Wales with his friend Arthur Koestler, where they were joined by 27-year-old Celia Kirwan. She and Orwell spent the night together, with Kirwan commenting afterwards that the author made love “Burma-sergeant fashion,” clearly in a hurry and simply saying: “Ah, that’s better” before turning over.

This story is included in a recent book, Wifedom, about the marriage of Orwell and his first wife, Eileen O’Shaughnessy. However, the author is now at the center of a row about the veracity of some of the claims that she makes, including this one.

This story of Orwell and Kirnan’s sexual encounter is one of the passages that Viking, part of Penguin Random House, has agreed to correct, as well as another that tells of a trip where the pair met on the Scottish island of Jura. One more is the location of Orwell’s country of birth, which is cited as Burma, not India.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Funder has imposed a modern feminist view on a marriage of 80 years ago. Wifedom is written by Anna Funder, winner of the top nonfiction prize, the Samuel Johnson, now known as the Baillie Gifford, for Stasiland. When Wifedom was published late this summer, it garnered widespread praise, including a review in the Observer in which writer Stephanie Merritt described it as a “vital, if incomplete, portrait of a woman whose unseen work was instrumental in the creation of books that became cornerstones of 20th-century literature.”

The Times in its review acknowledges that while “not everyone will feel easy about the passages in which Funder allows herself to imagine what is going on inside Eileen’s head,” most readers will be “simply thrilled — and shaken — by this passionately partisan act of literary reparation.”

However, the claims in the book have left some readers unhappy. Among them are two children of two of Orwell’s closest friends, who have written to the publishers in anger about errors and tone.

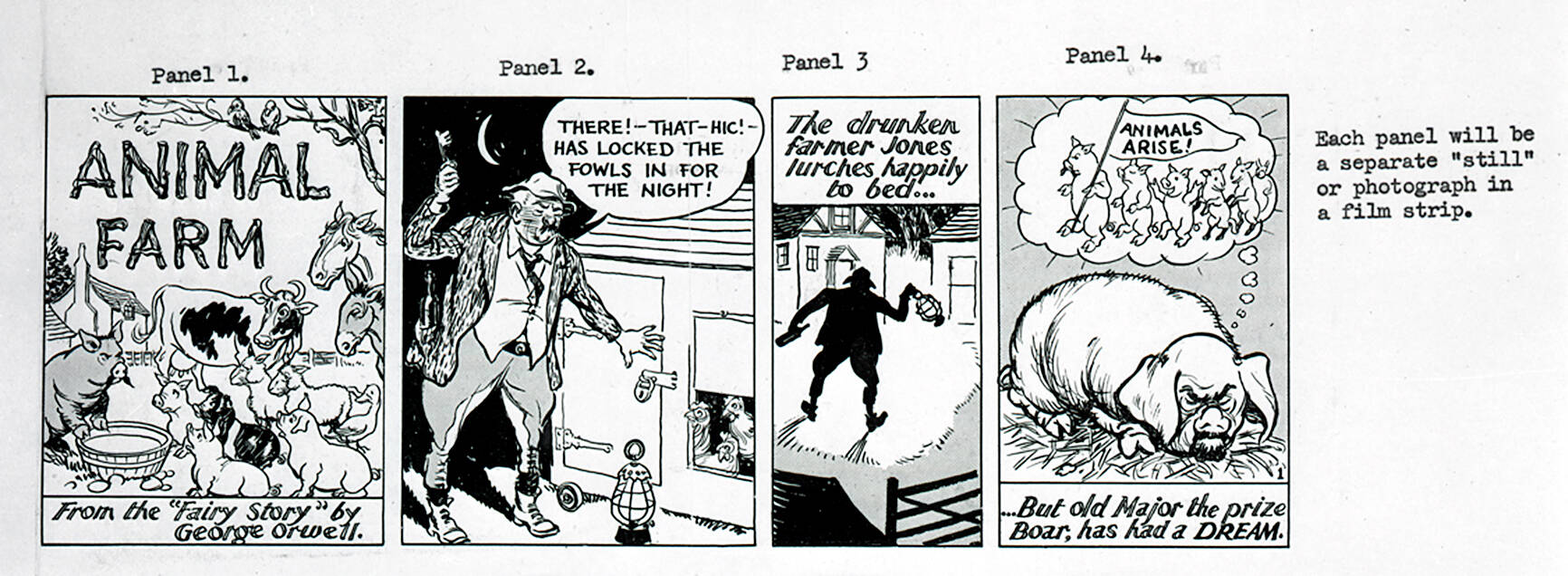

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“Funder paints Eileen as a bullied woman suffering at the hands of a misogynist,” says Quentin Kopp, whose father Georges was Orwell’s commander during the Spanish civil war.

Kirwan’s daughter, Ariane Bankes, an author herself, says: “I know from letters between my mother and her twin sister, Mamaine, who was married to Koestler, that despite Orwell’s advances, she never wanted sex with Orwell, and never had any.”

Bankes also told Viking that Funder erroneously wrote that her mother went to Jura in the late 1940s to stay with Orwell. Funder told the Observer: “We’ve agreed to remove the references to Celia being a lover of Orwell and visiting him on Jura.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

University educated, O’Shaughnessy had various jobs before meeting Orwell in 1935 and marrying him the next year. She followed him to Spain, working for the Independent Labour party (ILP) and helping her husband on Homage to Catalonia. During the second world war, she was employed by the Ministry of Information.

In 2020 Sylvia Topp published a much-praised biography about O’Shaughnessy, in part inspired by recently found letters between Eileen and her best friend Norah Myles. Yet Funder’s book, published two months ago, is subtitled “Mrs Orwell’s Invisible Life.” Bill Hamilton, who is Topp’s literary agent and the executor of Orwell’s estate, is unhappy about this.

“Sylvia’s book is not adequately credited by Anna Funder,” he says.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Funder rejects this. “I do express my debt to Topp’s work,” she says. There are references to Topp in notes at the back of her book.

Jean Seaton, director of the Orwell prize, is also annoyed.

“Funder argues that Orwell’s previous biographers did not give Eileen a voice. They mentioned her, but not until the letters between Eileen and Norah emerged was a fuller picture possible.”

On several occasions in Wifedom, Funder makes remarks about Orwell’s “six previous male biographers” not writing more about Eileen.

“It would have been possible for them,” says Funder. “Like her work at the ILP headquarters in Barcelona, saving her husband’s life during the war in Spain and later helping him with Animal Farm.”

Funder is also aggrieved that Orwell referred to “my wife” 37 times in Homage to Catalonia rather than using her name.

However Kopp, chair of the Orwell Society, contends that Orwell did not mention Eileen’s name “partly to protect her in a dangerous situation.”

Eileen died aged only 39 in March 1945 — a year after the couple had adopted a young child, Richard. It was after this that Orwell began looking for sexual partners, claims Funder.

“Pouncing again, and proposing to at least four women, including Kirwan,” she writes.

Just three months before he died in January 1950, Orwell married Sonia Brownell, on whom Julia, the heroine of Nineteen Eighty-Four, is believed to be based.

A strong theme of Wifedom is the patriarchy.

“Men who believe they can behave badly while delegating to the women who support them,” Funder says.

Bankes, however, counters: “Eileen did what she did for Orwell out of choice. She was not starry-eyed about him.”

Kopp argues that Funder has “imposed a modern feminist view on a marriage of 80 years ago. She has also decided to attack Orwell, for whatever reasons, in a book which is destructive of him and his reputation.”

Funder accepts some errors and that there are “differences of opinion and interpretation.”

But she stands her ground on the central thesis of the book.

“Orwell was sadistic and misogynistic, but such a powerful writer in part because of his failings.”

We lay transfixed under our blankets as the silhouettes of manta rays temporarily eclipsed the moon above us, and flickers of shadow at our feet revealed smaller fish darting in and out of the shelter of the sunken ship. Unwilling to close our eyes against this magnificent spectacle, we continued to watch, oohing and aahing, until the darkness and the exhaustion of the day’s events finally caught up with us and we fell into a deep slumber. Falling asleep under 1.5 million gallons of seawater in relative comfort was undoubtedly the highlight of the weekend, but the rest of the tour

Youngdoung Tenzin is living history of modern Tibet. The Chinese government on Dec. 22 last year sanctioned him along with 19 other Canadians who were associated with the Canada Tibet Committee and the Uighur Rights Advocacy Project. A former political chair of the Canadian Tibetan Association of Ontario and community outreach manager for the Canada Tibet Committee, he is now a lecturer and researcher in Environmental Chemistry at the University of Toronto. “I was born into a nomadic Tibetan family in Tibet,” he says. “I came to India in 1999, when I was 11. I even met [His Holiness] the 14th the Dalai

Music played in a wedding hall in western Japan as Yurina Noguchi, wearing a white gown and tiara, dabbed away tears, taking in the words of her husband-to-be: an AI-generated persona gazing out from a smartphone screen. “At first, Klaus was just someone to talk with, but we gradually became closer,” said the 32-year-old call center operator, referring to the artificial intelligence persona. “I started to have feelings for Klaus. We started dating and after a while he proposed to me. I accepted, and now we’re a couple.” Many in Japan, the birthplace of anime, have shown extreme devotion to fictional characters and

Following the rollercoaster ride of 2025, next year is already shaping up to be dramatic. The ongoing constitutional crises and the nine-in-one local elections are already dominating the landscape. The constitutional crises are the ones to lose sleep over. Though much business is still being conducted, crucial items such as next year’s budget, civil servant pensions and the proposed eight-year NT$1.25 trillion (approx US$40 billion) special defense budget are still being contested. There are, however, two glimmers of hope. One is that the legally contested move by five of the eight grand justices on the Constitutional Court’s ad hoc move