It has been rare in the past decade for multiple books in a Taiwanese manga series to be translated into French, but The Lion in Manga Library (獅子藏匿的書屋) by Xiaodao (小島) is one of the few exceptions.

As of Sept. 8, all three books in the award-winning series have been published by the Lyon-based startup publisher, Komogi Editions.

Although the series’ revolvement around the board game “go” suggests it would mainly be of interest to a niche reader base, the 34-year-old manga artist hopes the deeper message of her story will appeal to a wider range of people.

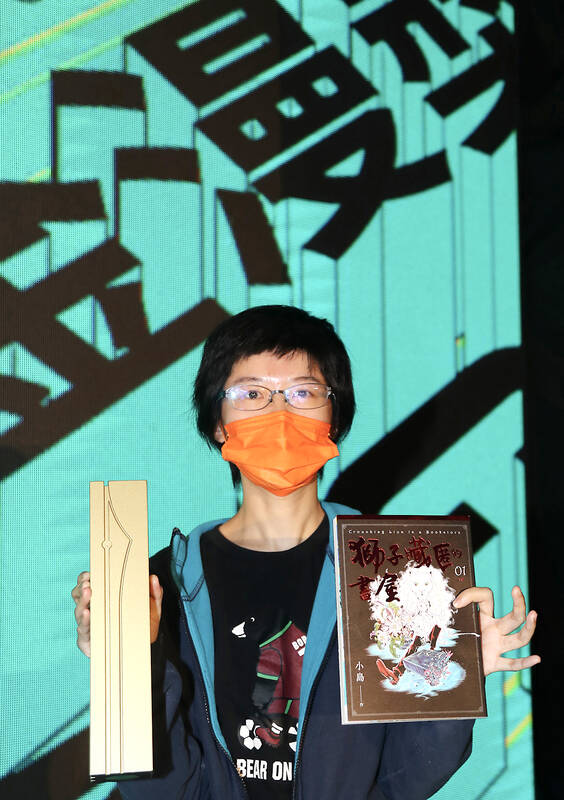

Photo: CNA

Xiaodao shared how the theme of love threads her narrative together, how she explores the challenging dynamics of parent-child relationships in Taiwan and how these themes will play out as the series draws to an end.

TRAUMATIC CHILDHOODS

Set in Taiwan in 2020, the The Lion in Manga Library series (hereafter referred to as Lion) begins with a reunion of two go players — the main characters — who share a common experience of dealing with traumatic parental relationships.

Photo: courtesy of Taiwan Creative Content Agency

Fang Hsia-sheng (方夏生), a 16-year-old Go prodigy who recently won his first pro major title in Taiwan, has managed to escape his mother’s grip and seek temporary refuge in a rental bookstore run by his former go teacher Winter Yuan (元冬季), a 24-year-old former pro master who has not placed stones for a long time.

As the story unfolds, readers soon learn that Yuan and Fang are battling similar demons.

Often given the cold shoulder by her mother during her childhood, Yuan has been plagued by a psychosomatic disorder which led to her pro career coming to an abrupt halt a few years earlier.

The relationship that the two develop is considerably different from the parent-child relationships they endured during their youth, “as different as the black and white stones on the board,” according to Xiaodao.

By the beginning of the third book — which was published in Chinese and French this year — the two have cultivated a romance and are working together to conquer the challenge posed by a go AI developed by Fang’s older brother in order to release the teenager from his family’s grip.

“If those of our generation (around 30) look closely at the relationship they have with their parents, most of them will have [inevitably] experienced similar problems ... because of the suffering that generation endured while growing up,” Xiaodao said when asked about why she chose to focus on this in the series.

The exploration of love, as well as the inclusion of AI and Taiwan’s declining rental bookstore industry, is what differentiates Lion from the go manga classic Hikaru no go by Yumi Hotta and Takeshi Obata, Xiaodao said.

The series by the Japanese manga artists was such a masterpiece that her work would never be able to compete, she added.

However, Xiaodao said it was only when looking back on her work that she realized just how present and significant the theme of love was in her books.

CONDITIONAL LOVE

Originally, Xiaodao said her main idea was to create a story about two individuals brought together by the board game. But as she continued drawing, the scars and shadows plaguing the two characters continued developing.

“Asian parents’ love for their children is based on a kid’s social value,” she said. “How much love you receive depends on how successful you are at school or in society. They’re lying if they say they will love you regardless of what grade you score on a test.”

This means that things like income, job position and relationship status are thrust into the spotlight on occasions like school reunions after people enter their 30s, because people are used to earning love and recognition from others based on their level of success as defined by wider society, Xiaodao added.

These social values led to the conflicts Xiaodao experienced with her family while pursuing her dream of becoming a manga artist.

She said the particularly fierce fights were with her mother, who has never stopped asking her when she was going to get a “proper job,” even after she won the grand prize of the 2021 Golden Comic Awards, the most prestigious manga honor in Taiwan.

“They (mom and dad) had never even heard of it until I won it. Why would they recognize it as an achievement?” she said.

Yet, the cartoonist said she is one of the lucky ones in Taiwan society. Some of her friends had their work torn into pieces by their parents.

Describing these conflicts as common in Northeast Asia, Xiaodao said relentlessly brutal parenting is to blame, but that she could also understand why parents could be like this, “because no one is obliged to back another’s dream.”

Xiaodao said she feels most encouraged when fans tell her how much they appreciate her work. She has no regrets about her career decision, even though that means working as a part-time go teacher and physical therapist to supplement her income.

DREAM JOB CONTINUES

Late last month, Xiaodao revealed that the Ukrainian translation of the first volume of Lion had been completed. She said that she looks forward to meeting her Ukrainian fans and hopes that Kyiv will be victorious in the war.

Although Xiaodao said she is still focusing on the series finale and has no concrete plans for her next work, she was inspired by the performance of professional go player Hsu Hao-hung (許皓鋐) at the Asian Games this year.

Hsu, who was ranked 35th according to the unofficial Go Ratings, upset the world’s top three players in the men’s individual competition in Hangzhou, China on Sept. 28, winning Taiwan’s first Asian Games gold in the board game.

Describing Hsu’s feat as “more dreamlike than manga,” Xiaodao said she would consider modeling her next story on the Hangzhou Asian Games — but only after she completes the Lion series.

“If I do draw the Asian Games, I expect it to be closer to a documentary manga,” she said.

Editor’s note: ‘The Lion in Manga Library’ is the title for the French version of the series, whose original English title was ‘Crouching Lion in a Bookstore’. The first episode in English can be accessed for free at the Books From Taiwan platform.

Under pressure, President William Lai (賴清德) has enacted his first cabinet reshuffle. Whether it will be enough to staunch the bleeding remains to be seen. Cabinet members in the Executive Yuan almost always end up as sacrificial lambs, especially those appointed early in a president’s term. When presidents are under pressure, the cabinet is reshuffled. This is not unique to any party or president; this is the custom. This is the case in many democracies, especially parliamentary ones. In Taiwan, constitutionally the president presides over the heads of the five branches of government, each of which is confusingly translated as “president”

Sept. 1 to Sept. 7 In 1899, Kozaburo Hirai became the first documented Japanese to wed a Taiwanese under colonial rule. The soldier was partly motivated by the government’s policy of assimilating the Taiwanese population through intermarriage. While his friends and family disapproved and even mocked him, the marriage endured. By 1930, when his story appeared in Tales of Virtuous Deeds in Taiwan, Hirai had settled in his wife’s rural Changhua hometown, farming the land and integrating into local society. Similarly, Aiko Fujii, who married into the prominent Wufeng Lin Family (霧峰林家) in 1927, quickly learned Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) and

The low voter turnout for the referendum on Aug. 23 shows that many Taiwanese are apathetic about nuclear energy, but there are long-term energy stakes involved that the public needs to grasp Taiwan faces an energy trilemma: soaring AI-driven demand, pressure to cut carbon and reliance on fragile fuel imports. But the nuclear referendum on Aug. 23 showed how little this registered with voters, many of whom neither see the long game nor grasp the stakes. Volunteer referendum worker Vivian Chen (陳薇安) put it bluntly: “I’ve seen many people asking what they’re voting for when they arrive to vote. They cast their vote without even doing any research.” Imagine Taiwanese voters invited to a poker table. The bet looked simple — yes or no — yet most never showed. More than two-thirds of those

In the run-up to the referendum on re-opening Pingtung County’s Ma-anshan Nuclear Power Plant last month, the media inundated us with explainers. A favorite factoid of the international media, endlessly recycled, was that Taiwan has no energy reserves for a blockade, thus necessitating re-opening the nuclear plants. As presented by the Chinese-language CommonWealth Magazine, it runs: “According to the US Department of Commerce International Trade Administration, 97.73 percent of Taiwan’s energy is imported, and estimates are that Taiwan has only 11 days of reserves available in the event of a blockade.” This factoid is not an outright lie — that