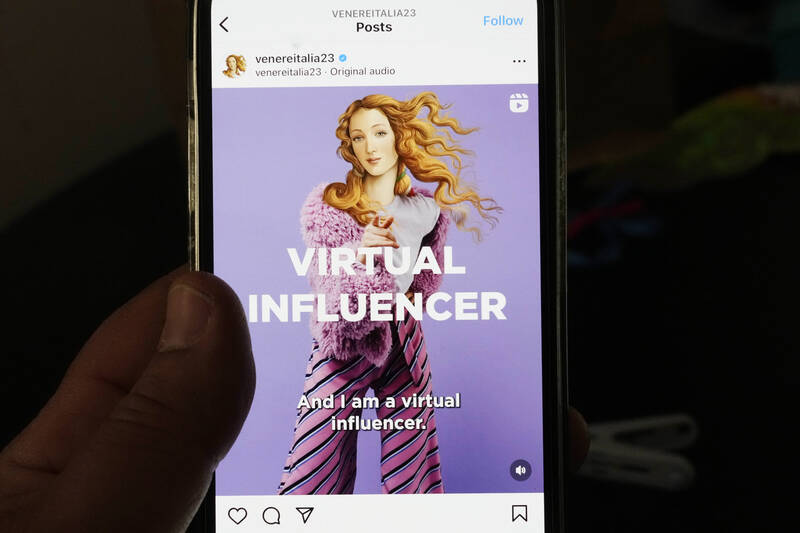

The Italian tourism ministry thought it had a sure-fire way to bring travelers into the country: turning a 15th century art icon into a 21st century “virtual influencer.”

The digital rendition of Venus, goddess of love, based on Sandro Botticelli’s Renaissance masterpiece Birth of Venus, can be seen noshing on pizza and snapping selfies for her Instagram page. Unlike the original, this Venus is fully clothed. The influencer claims to be 30, or “maybe just a wee bit (older) than that.”

But the new ad campaign is facing significant backlash — with critics calling it a “new Barbie” that trashes Italy’s cultural heritage.

Photo: AP

The tourist campaign “trivializes our heritage in the most vulgar way, transforming Botticelli’s Venus into yet another stereotyped female beauty,” Livia Garomersini, an art historian and activist with Mi Riconosci, an art and heritage campaign organization, said in a response to the project last month.

The yearlong campaign, produced by national tourism agency ENIT and advertising group Armando Testa, is estimated to have cost nine million euros (about US$9.9 million), according to ENIT CEO Ivana Jelinic.

Jelinic said that the campaign was designed for overseas markets to attract younger tourists. The online Venus launched in Italy on April 20 and made her international debut in Dubai at the Arabian Travel Market earlier this week.

Photo: AP

“We liked the idea that it would be a work of art that is timeless,” Jelinic said, adding that Botticelli’s Venus “seemed to us like a immortal icon who could represent Italy well.”

Already the new Venus has been memed mercilessly online, appearing among trash bins, alongside Mafia boss Matteo Messina Denaro and in other less-than godly places.

The criticism extends beyond the use of a masterpiece to the manner in which the campaign was orchestrated, including its use of stock images and other gaffes like a promotional video featuring a winery in Slovenia, used as a stand-in for Italy.

An even greater sin for many is the campaign’s slogan, “Open to Meraviglia” (Open to Wonder), because it mixes English into an Italian tourist campaign even as the country’s government seeks to protect the Italian language as a pillar of its culture.

There are other language faux pas.

On the campaign’s Web site, an automatic translator turned Brindisi, a southern Italian port town, into its literal English definition: “Toast,” according to Matteo Flora, a professor at the University of Pavia. That part of the Web site has now been obscured.

“Let’s not talk about the creativity point of view,” said Flora, “You may like (the campaign) or not, but on a technical point of view, it has been... a sort of avalanche of problems.”

That includes a failure to secure domains, allowing anyone to snatch the material and mock the project with it.

Flora said the campaign also wasted money. The campaign’s creative team chose to use the “intelligence of human creativity,” rather than artificial intelligence, to build the virtual Venus — but Flora showed how he could quickly come up with a similar campaign using AI at a cost of 20 euros. His social media posts have been shared by thousands of people.

The use of a likeness of Botticelli’s masterpiece has been lambasted by art historians as well, who say it vastly diminishes the beauty and mystery of the 15th century original.

“Perhaps Botticelli would not be happy about this,” said Massimo Moretti, a professor of art history at the University of Rome, Sapienza.

Any use of an iconic image like the Birth of Venus risks striking a cultural nerve, marketing experts say.

“The more you try to alter something that’s historic, probably the greater the outcry,” said Larry Chiagouris, professor of marketing at Pace University’s Lubin School of Business.

“People are going to say, ‘You’re changing the culture. You’re changing who we are, because it’s part of our history,’” Chiagouris added.

“I didn’t like the fact that they used the Botticelli Venus like that, since it is a piece of art,” Riccardo Rodrigo, a high school student in Rome, said. “They made it something social friendly to amuse Gen Z, I think it was unnecessary since it can be used just like it is and not modified like they did.”

The Uffizi Galleries, which houses Botticelli’s Birth of Venus in Florence, declined to comment on the campaign.

For the creators of the campaign, however, any press is good press.

“It has become so viral,” said Jelinic of ENIT, adding that “Web users have made her come alive” even when placing the new Venus in unglamorous places.

“I find (it) interesting in terms of social communication,” Jelinic said. “Our campaign is more appealing than (critics) want to admit.”

Tourism officials plan to expand the campaign through the use of billboards as well as video screens in airports and railways.

In the next few months tough decisions will need to be made by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and their pan-blue allies in the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). It will reveal just how real their alliance is with actual power at stake. Party founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) faced these tough questions, which we explored in part one of this series, “Ko Wen-je, the KMT’s prickly ally,” (Aug. 16, page 12). Ko was open to cooperation, but on his terms. He openly fretted about being “swallowed up” by the KMT, and was keenly aware of the experience of the People’s First Party

Aug. 25 to Aug. 31 Although Mr. Lin (林) had been married to his Japanese wife for a decade, their union was never legally recognized — and even their daughter was officially deemed illegitimate. During the first half of Japanese rule in Taiwan, only marriages between Japanese men and Taiwanese women were valid, unless the Taiwanese husband formally joined a Japanese household. In 1920, Lin took his frustrations directly to the Ministry of Home Affairs: “Since Japan took possession of Taiwan, we have obeyed the government’s directives and committed ourselves to breaking old Qing-era customs. Yet ... our marriages remain unrecognized,

During the Metal Ages, prior to the arrival of the Dutch and Chinese, a great shift took place in indigenous material culture. Glass and agate beads, introduced after 400BC, completely replaced Taiwanese nephrite (jade) as the ornamental materials of choice, anthropologist Liu Jiun-Yu (劉俊昱) of the University of Washington wrote in a 2023 article. He added of the island’s modern indigenous peoples: “They are the descendants of prehistoric Formosans but have no nephrite-using cultures.” Moderns squint at that dynamic era of trade and cultural change through the mutually supporting lenses of later settler-colonialism and imperial power, which treated the indigenous as

Standing on top of a small mountain, Kim Seung-ho gazes out over an expanse of paddy fields glowing in their autumn gold, the ripening grains swaying gently in the wind. In the distance, North Korea stretches beyond the horizon. “It’s so peaceful,” says the director of the DMZ Ecology Research Institute. “Over there, it used to be an artillery range, but since they stopped firing, the nature has become so beautiful.” The land before him is the demilitarized zone, or DMZ, a strip of land that runs across the Korean peninsula, dividing North and South Korea roughly along the 38th parallel north. This