Jan. 2 to Jan. 8

When Thomas Band set out for Taiwan in 1912, he made sure he brought one item with him: a soccer ball.

The 26-year-old British missionary was the captain of his soccer team at seminary school, and he believed that the sport embodied the physical and mental strength that his profession needed.

Photo courtesy of Kuo Jung-pin

Physical education was not a common subject then, and as principal of Tainan’s Presbyterian Church High School (renamed Chang Jung High School in 1939), he at first had to drag the students from their dorms after school to the field. But soon, the sport took off and the school became a local powerhouse, representing Taiwan in the 1940 national tournament in Japan.

Meanwhile in northern Taiwan, Japanese educators hoping to infuse more Western elements into the curriculum also launched their own soccer clubs, and starting in the late 1920s, schools across the colony regularly engaged in intense regional and national tournaments that attracted fervent spectators. The rivalry between the predominantly Taiwanese Presbyterian school and the mostly-Japanese Tainan First High School was the most heated, and brawls were common after extremely physical matches.

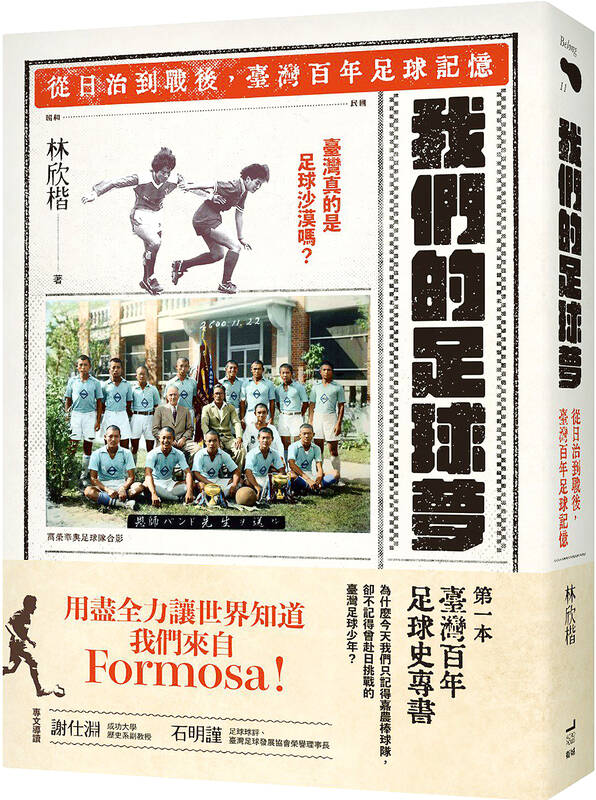

“For Taiwanese, soccer was not only a sport to train your body and mind, it was a way for them to break out of their status as a colonized people, and through fair competition, challenge the Japanese and even the world,” Lin Hsin-kai (林欣楷) writes in his new book, Our Soccer Dreams (我們的足球夢).

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Despite this promising beginning, Taiwan never found much international success except for a miraculous run by its women’s team in the 1970s and 80s. As the craze of the World Cup subsides, there’s been much discussion about how to boost Taiwan’s profile in the sport. With the recent release of Lin’s book, it’s an ideal time to examine in detail the sport’s lesser known early days.

RISING SPORT

Several years after Band’s arrival, students could be seen playing barefeet through the streets and in the parks, Lin writes. Alumnus and former player Hung Nan-hai (洪南海) recalls seeing older classmates use the city’s southeast gate as a soccer goal.

Photo courtesy of books.com.tw

By 1920, the Presbyterian school had two soccer teams, and it was the most popular activity during recess. Upon graduation, Band brought the students on an exchange to China with church schools there, with soccer matches being one of the major activities.

The sport developed independently in the north, being promoted by the Japanese around the same time. In 1918, soccer became part of Japan’s school curriculum, and by extension Taiwan. However, baseball was still closest to people’s hearts — to the point that the Asahi Shimbun newspaper published a series of articles warning of the harmful effects of baseball, arguing that it wasn’t really a full-body sport and that it caused the students to neglect their studies. Governor-general Nogi Marusuke even chimed in: “It’s very harmful to spend so much time and enthusiasm on the results of a match.”

Taihoku Second High School principal Hanshiro Kawase agreed, going against the grain to promote soccer, kendo and swimming. He believed that soccer was a better team sport than baseball and more conducive to teaching the importance of cooperation, Lin writes. Japanese soldiers docked in Keelung could be seen competing with students during their down time.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

This also happened in the south, as the crew of a visiting British warship played a friendly match with the Presbyterian students. The students easily beat the soldiers and made the front page of the newspapers.

INTENSE RIVALRY

In November 1929, the Presbyterian Middle School and Tainan First High launched the Southern Soccer League with Band as president. Two schools from Kaohsiung also joined, and founding members included British, Japanese and Taiwanese.

With missionary Thomas Barclay donating the trophy, the inaugural Barclay Cup kicked off on Nov. 30, 1929, with four Tainan schools competing; the Kaohsiung schools did not join due to the distance. The Presbyterians won the first of three straight championships and the matches were reportedly very physical as foul rules were loose.

The news spread to Taipei, and the island-wide Mitsuzawa Cup took place the following year with 13 teams competing. It became one of the four regular soccer events taking place in the capital during the 1930s.

Presbyterian Middle School and Tainan First High developed an intense rivalry during these years, and raucous, cheering supporters could be seen at their games. The government’s increasingly intrusive measures toward Christian schools (such as mandating that they worship at Shinto shrines) further fueled the animosity of the students toward their Japanese counterparts. Post-match brawls were common, and the authorities tacitly allowed them to happen as a way for people to blow off steam as imperialism grew.

In 1932, the Presbyterians suffered a shocking loss to Tainan First High, and it was seen as the biggest shame in school history. With funding from the alumni association, the students trained all summer in 1933 and easily exacted their revenge in September. They then headed north to play the three top Taipei teams, winning two out of three matches.

Most players returned for the 1934 school year, with the star being Ping Tien-ming (兵田明), an ethnic Siraya multi-sport athlete nicknamed “The All-Powerful Fleet Carrier” (萬能航空母艦). With the arrival of Liu Chao-ben (劉朝本), the squad was considered the strongest ever, and the school arranged for them to head to Japan and square off against its top teams.

They did not stand a chance against Kobe First High School, losing 10-0. The exhausted, dejected team then took on Hiroshima First High School, with the game ending in a 1-1 tie.

OFFICIAL COMPETITION

The Taiwan Min Pao (台灣民報) newspaper in 1931 named the colony’s four rising sports stars, including “Soccer Overlord” Lin Chao-chuan (林朝權) of the Presbyterian alumni team. Although his squad found success in Taiwan, they were not yet allowed to compete in Japan.

This rule was reversed in 1938. That year, the all-Japanese Taihoku High School beat out the competition to represent Taiwan, but they lost in the first round. In 1940, Presbyterian Middle School (by then renamed Chang Jung High School) finally earned its chance to compete, becoming the first all-Taiwanese squad to play in official competition. They were also knocked out in the first round, but that year’s dark-horse winner also came from a colony — Korea’s Boseong High School.

Sports activities came to a halt as World War II intensified. Official soccer matches resumed under the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) with the Provincial Soccer Tournament in July 1946, and Chang Jung High School’s alumni squad took home the trophy.

At first, Lin was happy to help the new government rebuild Taiwan’s sports scene, serving as director of the Provincial Sports Association. However, after his beloved teacher Lin Mao-sheng (林茂生) “disappeared” in the aftermath of the 228 Incident, he left for China and never returned.

In November 1947, the KMT put on a national sports tournament in Shanghai to celebrate Taiwan’s “return” to the motherland. Shanghai reporters came to Taiwan to examine the local sports scene, concluding that its weakest points were soccer and basketball.

Upon hearing this, the cash-strapped provincial government did not send a soccer team to the competition. Lin Hsin-kai writes that this was the beginning of the “Taiwanese cannot play soccer” label that has haunted the nation for 70 years, especially as the national team’s success in the 1950s and 1960s relied on borrowed players from Hong Kong.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

No one saw it coming. Everyone — including the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) — expected at least some of the recall campaigns against 24 of its lawmakers and Hsinchu Mayor Ann Kao (高虹安) to succeed. Underground gamblers reportedly expected between five and eight lawmakers to lose their jobs. All of this analysis made sense, but contained a fatal flaw. The record of the recall campaigns, the collapse of the KMT-led recalls, and polling data all pointed to enthusiastic high turnout in support of the recall campaigns, and that those against the recalls were unenthusiastic and far less likely to vote. That

Behind a car repair business on a nondescript Thai street are the cherished pets of a rising TikTok animal influencer: two lions and a 200-kilogram lion-tiger hybrid called “Big George.” Lion ownership is legal in Thailand, and Tharnuwarht Plengkemratch is an enthusiastic advocate, posting updates on his feline companions to nearly three million followers. “They’re playful and affectionate, just like dogs or cats,” he said from inside their cage complex at his home in the northern city of Chiang Mai. Thailand’s captive lion population has exploded in recent years, with nearly 500 registered in zoos, breeding farms, petting cafes and homes. Experts warn the

A couple of weeks ago the parties aligned with the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), voted in the legislature to eliminate the subsidy that enables Taiwan Power Co (Taipower) to keep up with its burgeoning debt, and instead pay for universal cash handouts worth NT$10,000. The subsidy would have been NT$100 billion, while the cash handout had a budget of NT$235 billion. The bill mandates that the cash payments must be completed by Oct. 31 of this year. The changes were part of the overall NT$545 billion budget approved

The unexpected collapse of the recall campaigns is being viewed through many lenses, most of them skewed and self-absorbed. The international media unsurprisingly focuses on what they perceive as the message that Taiwanese voters were sending in the failure of the mass recall, especially to China, the US and to friendly Western nations. This made some sense prior to early last month. One of the main arguments used by recall campaigners for recalling Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers was that they were too pro-China, and by extension not to be trusted with defending the nation. Also by extension, that argument could be