Andy Warhol once said “Art is what you can get away with.” Now a legal fight surrounding his prints of Prince threatens to upend the world of pop art as well as music, books and videos.

In a fight that has outlived both men, the US Supreme Court will consider whether Warhol was within his rights to create 16 images of the musician in 1984 using a copyrighted photograph of the musician. The case could reshape the fair-use defense to copyright infringement for follow-on works, affecting music, videos and books, as well as Warhol’s iconic art.

IMPLICATIONS

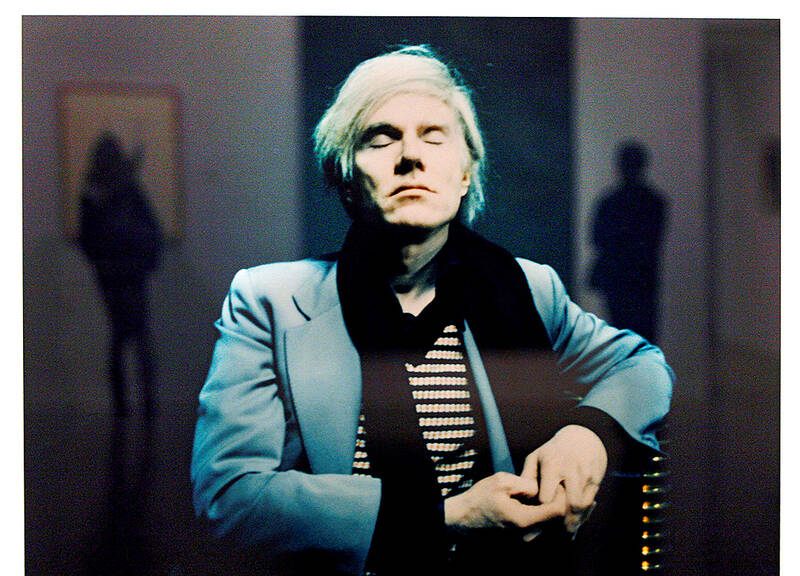

Photo: Reuters

Both sides are emphasizing the potential stakes. The Association of American Publishers says expanding the fair-use defense could have a “catastrophic impact” on that industry, while representatives of the art community say the opposite result could have a chilling effect on artists and museums.

The case “is incredibly important to many, many people,” said Bruce Ewing, who co-chairs the intellectual property practice at Dorsey & Whitney in New York. “It has potential implications well beyond art. You’re talking about music, publishing, and many different types of creative industries.”

The showdown could draw the justices into an unfamiliar world, testing their eagerness — and perhaps ability — to assess differences between works of art or literature that share a common core.

Photo: Reuters

The path to the Supreme Court began in 1981 with a black-and-white photo taken of Prince by rock-and-roll photographer Lynn Goldsmith. Three years later, with Prince at the peak of his popularity, Vanity Fair paid Goldsmith a US$400 licensing fee so that Warhol could use the photo as an “artist’s reference” to create an image of the singer-songwriter for the magazine.

Warhol then created what became known as the Prince Series, consisting of 16 silkscreens, screen prints and sketches that gave his subject what the foundation called “a flat, impersonal, disembodied, mask-like appearance.”

Vanity Fair published one image in the 1984 issue. Warhol died three years later, and his copyrights were transferred to the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

Photo: AFP

PRINCE’S DEATH

When Prince died in 2016, Vanity Fair parent Conde Nast paid the foundation US$10,250 to run a different image from the Prince Series on the magazine’s cover, without giving Goldsmith any additional payment or credit. Goldsmith then accused the foundation of copyright infringement.

A federal trial judge tossed out Goldsmith’s claim, but the New York-based 2nd US Circuit Court of Appeals reinstated it. The panel said Warhol’s image wasn’t “transformative” — and therefore wasn’t fair use — because it didn’t do enough to change the appearance of Goldsmith’s photo.

Warhol’s work “retains the essential elements of the Goldsmith photograph without significantly adding to or altering those elements,” Judge Gerard Lynch wrote for the appeals court.

At the Supreme Court, the foundation says the appeals court was wrong to focus solely on the visual appearance of the images. The foundation says the key question is whether the second work conveys a new “meaning or message.”

“While Goldsmith portrayed Prince as a vulnerable human, Warhol made significant alterations that erased the humanity from the image, as a way of commenting on society’s conception of celebrities as products, not people,” Roman Martinez, the foundation’s lawyer, argued in court papers. “The Prince Series is thus transformative.”

ALTERING A SONG

The foundation’s filing invokes Warhol’s famous Campbell’s soup can paintings — and a hint the Supreme Court may have dropped about those works last year. Ruling in a software copyright case, the court said a painting that replicates an advertising logo as “a comment about consumerism” may fall within fair use.

But Goldsmith says the foundation’s “meaning or message” approach would put judges in an impossible position.

“Courts cannot sensibly discern the meaning of art when artists, critics and the public often disagree about what art signifies,” contended Goldsmith’s lawyer, Lisa Blatt.

The brief points to Jackson Pollock, John Lennon, Pablo Picasso and Freddie Mercury as artists whose work defied any objective understanding, sometimes intentionally so.

“I’m looking to see if the justices understood any of the references to art and pop culture in the briefs,” Blatt quipped recently while speaking at Georgetown University Law Center.

Goldsmith’s brief also argues that the foundation’s “meaning or message” approach ignores the other fair-use factors listed in the 1976 Copyright Act, including the impact on the market for the original work.

Goldsmith has support from the Recording Industry Association of America and the National Music Publishers’ Association. The Motion Picture Association filed a brief that didn’t formally take sides in the case but said the Warhol position would “threaten the protection afforded all manner of copyrighted works.”

The Biden administration is also supporting Goldsmith, suggesting the court protect Warhol’s creation of the Prince Series but not the foundation’s commercial licensing of the Prince image. The images are now worth large sums of money, with one selling for US$173,664 in 2015.

That approach makes some art advocates uneasy. It makes no sense to say a work could be fair use when it’s created but not once it’s licensed or sold, said Jaime Santos, a Washington lawyer who filed a brief for a groups that include foundations for the late artists Robert Rauschenberg, Roy Lichtenstein and Joan Mitchell.

“There’s not a ton of confidence that those same principles won’t apply to the actual creation of the work itself,” Santos said. “So I think it really just kind of makes a mash of the case law and makes things pretty scary for anyone from museums to foundations to even smaller artists who are making works and using prior works as artists have done for centuries.”

The court is scheduled to rule by late June in the case, Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith, 21-869.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.