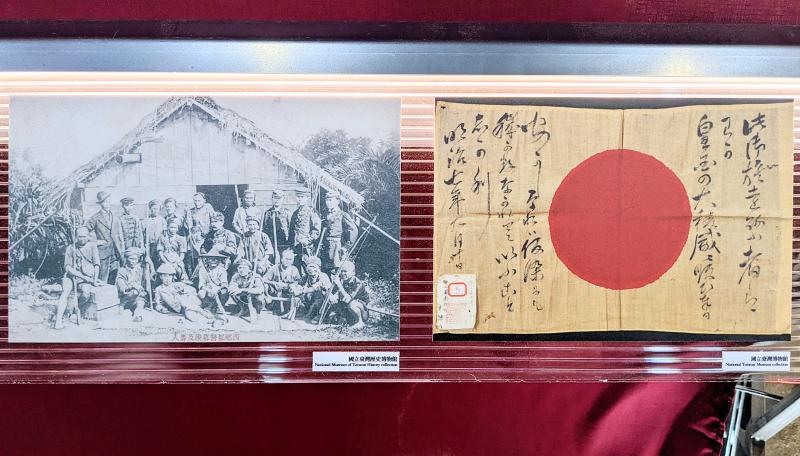

A recording of Paiwan singers from Sinevaudjan Village echoes through the exhibition room, the lyrics looking back at the hardships their ancestors suffered to give them the life they have today. Nearly 150 years ago, the village was wiped off the map by the Japanese during the Mudan Incident (牡丹社事件), and it took 36 years for the people to return and rebuild it.

Due to a misunderstanding caused by language and cultural barriers, the ancestors of these singers — along with those from neighboring Kukus — killed 54 shipwrecked Ryukyuan sailors who had accidentally wandered into their territory in 1871. Their actions triggered a Japanese punitive expedition three years later that alarmed the Qing Dynasty, who long-treated Taiwan as a remote backwater that wasn’t worth investing in.

It was a pivotal moment in East Asian history. The Qing started paying more attention to governing and defending Taiwan, while Japan annexed the Kingdom of Ryukyu, its first move in what would be decades of imperial expansion.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Both Paiwan villages were burnt down, and for more than a century, the events were told exclusively from Japanese, Chinese and Western perspectives. Over the past 20 years, experts and locals have been reconstructing a new historical interpretation with the Paiwan as the main subjects. Earlier this month, Mudan Township unveiled new statues of Paiwan leader Aruqu Kavulungan and his son, who were killed in the incident but left out of the conventional narrative.

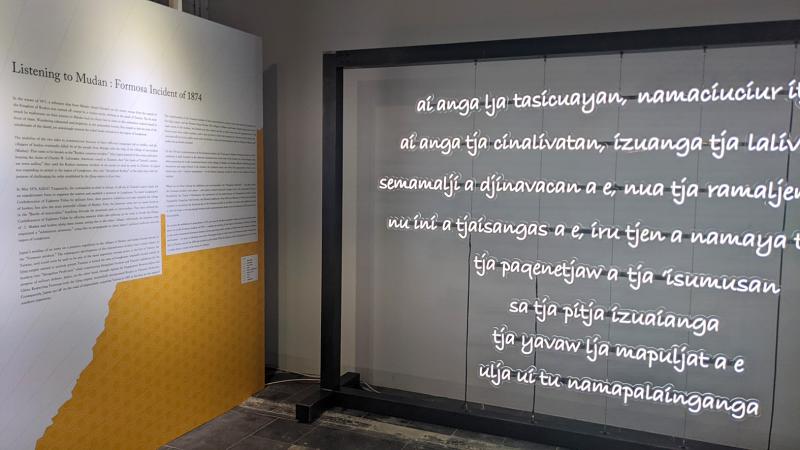

This display in Huashan 1914 Creative Park is a teaser for later next month’s Listening to Mudan: Formosa Incident of 1874 (聆聽牡丹的聲音) audiovisual exhibition that literally returns the voice to the Paiwan on their traditional land in Pingtung County. The Huashan exhibition closes on June 8, and the Pingtung event opens on June 24.

The Mudan Incident is often connected to the Rover Incident of 1867, which happened further to the south and was also triggered by Paiwan warriors killing shipwrecked foreigners — in this case Americans.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

This story was recently dramatized into last year’s hit mini-series Seqalu, drawing much public interest to the history of this area. The research that led to this exhibition is the result of the International Conference on Encounters between Southern Formosa and World, which was held in November 2019, and two years of field research into both incidents by Story Studio (故事).

The Taipei display offers an atmospheric general overview of the events in Chinese and English, but in Pingtung visitors can listen to recordings of Kukus and Sinevaudjan descendants telling their accounts of the incident, which have been passed on orally through the generations, in the Paiwan language and tradition. This is symbolic because the original dispute was caused by cultural and linguistic differences, and most visitors will have to rely on the translations to understand it.

The Pingtung show will also provide transportation and possible tours to several historic sites related to the incident, including one of the main battlefields that can be explored through riverside trails restored earlier this year. Also on the list are the graves of the 54 Ryukuan victims and a memorial to the incident erected by the Japanese in 1935. The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) scratched off the memorial’s text after World War II, and it was only restored in 2020.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

More details will be announced later next month.

This is the year that the demographic crisis will begin to impact people’s lives. This will create pressures on treatment and hiring of foreigners. Regardless of whatever technological breakthroughs happen, the real value will come from digesting and productively applying existing technologies in new and creative ways. INTRODUCING BASIC SERVICES BREAKDOWNS At some point soon, we will begin to witness a breakdown in basic services. Initially, it will be limited and sporadic, but the frequency and newsworthiness of the incidents will only continue to accelerate dramatically in the coming years. Here in central Taiwan, many basic services are severely understaffed, and

Jan. 5 to Jan. 11 Of the more than 3,000km of sugar railway that once criss-crossed central and southern Taiwan, just 16.1km remain in operation today. By the time Dafydd Fell began photographing the network in earnest in 1994, it was already well past its heyday. The system had been significantly cut back, leaving behind abandoned stations, rusting rolling stock and crumbling facilities. This reduction continued during the five years of his documentation, adding urgency to his task. As passenger services had already ceased by then, Fell had to wait for the sugarcane harvest season each year, which typically ran from

It is a soulful folk song, filled with feeling and history: A love-stricken young man tells God about his hopes and dreams of happiness. Generations of Uighurs, the Turkic ethnic minority in China’s Xinjiang region, have played it at parties and weddings. But today, if they download it, play it or share it online, they risk ending up in prison. Besh pede, a popular Uighur folk ballad, is among dozens of Uighur-language songs that have been deemed “problematic” by Xinjiang authorities, according to a recording of a meeting held by police and other local officials in the historic city of Kashgar in

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) was out in force in the Taiwan Strait this week, threatening Taiwan with live-fire exercises, aircraft incursions and tedious claims to ownership. The reaction to the PRC’s blockade and decapitation strike exercises offer numerous lessons, if only we are willing to be taught. Reading the commentary on PRC behavior is like reading Bible interpretation across a range of Christian denominations: the text is recast to mean what the interpreter wants it to mean. Many PRC believers contended that the drills, obviously scheduled in advance, were aimed at the recent arms offer to Taiwan by the