For Laura Bates, it began with a heavy piece of gold jewelery that her mother found on the passenger seat of the family car. It was a gift from her grandparents. Her mother, after two daughters, had been rewarded for giving birth to a son.

“I am five years old,” Bates writes, “and have no idea I’ve already been weighed, valued and found wanting.”

This incident is the first on what the feminist writer and activist calls “my list.” She encourages all women to make one, charting a life in sexism, from the playground to the street to the workplace.

“By the time I leave university, aged 20,” Bates writes, “I have been sexually assaulted, pressured to perform topless in a theater production (I stand my ground, but the experience leaves me in tears) and cornered in the street by two men shouting, ‘We’re going to part those legs and fuck that cunt.’”

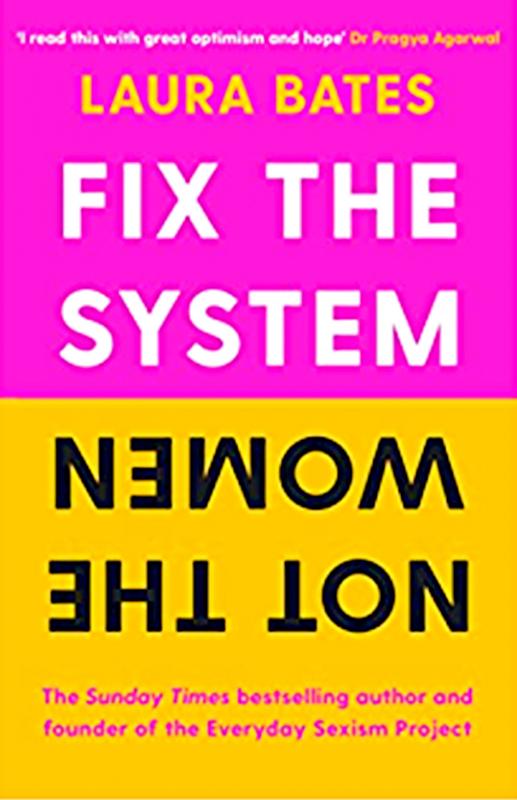

Fix the System, Not the Women is an attempt to highlight “the interlocking systems of domination that define our reality” — and to pull apart the myth that women are complicit in our own oppression.

Bates’s central message, which she has developed through her Everyday Sexism Project, the online forum that has now received 200,000 stories of sexism and misogyny from all over the world, and books including Girl Up (2016) and Men Who Hate Women (2020), is that there is a spectrum of gender inequality.

Sexist jokes and stereotypes are at one end. Rape, domestic abuse, female genital mutilation and so-called “honor” killings are at the other. Maternity discrimination, workplace sexual harassment, the gender pay gap “and so much more” lie somewhere in between.

What if, Bates asks, none of it is actually women’s fault? What if women can’t network, mentor, charm, assert and lean in their way out of sexism because this is a system that is rigged against them? A system that relies on its own invisibility for its preservation.

Bates pursues her thesis across five key areas: education, policing, criminal justice, media and politics. The fact that only a quarter of the Cabinet are women might just explain why working mothers lost their jobs at far higher rates than fathers during the COVID-19 pandemic, and new mothers were forced to give birth alone while pubs were allowed to open.

But the most rousing sections of the book are on male violence and the burden on women to keep themselves safe. When a woman is killed, it is often called “an isolated incident,” and yet a woman is murdered by a man in the UK every three days.

Bates is scathing about Priti Patel’s support for an app to log women’s movements, on top of managing all the other gear they are advised to carry. As a society “we cannot stop finding excuses for male violence,” she writes.

Despite the increased prominence of feminist campaigns, charges in rape cases are now exactly half what they were in 2015–16. Too often, decisions about whether or not to proceed to trial for rape rely on whether the woman fits the societal profile of the “perfect victim:” ie, those who are “sweet and pretty and innocent and careful and didn’t stray off the path or talk to the wolf.”

And also, importantly, white.

Fix the System contains plenty of suggestions for reform, including apps that track the movements of men convicted of crimes against women, and banning non-disclosure agreements that gag staff who have experienced maternity discrimination.

Bates also reminds us that if we want to tackle oppression in one sphere, we need to be aware of its overlap with others. Black women are four times as likely to die in pregnancy or childbirth in the UK, yet rarely see themselves represented in campaigns to reach out to expectant mothers. Disabled women are twice as likely to suffer domestic abuse, but just one in 10 spaces in refuges is accessible to those with physical disabilities.

But Bates is adamant that it’s not her job to find solutions. Hundreds already exist, “ignored and unused” in reports and campaign materials of feminist and civil rights organizations. Which made me wonder: how many men will read Fix the System?

In recent years, books such as Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race and White Fragility have been bought in huge numbers by white people. Because, as Bates says: “this is not our mess to clean up.” Sadly, I suspect the feminist publishing boom has passed most male readers by.

It would be heartening to think that Fix the System could be the book to change that. It’s an astute and persuasive page-turner, a clear-sighted, compelling examination of injustice. I was haunted by the story of a woman attacked by her ex-husband, who smashed her head so hard against a BMW that it dented the bodywork and left her needing hospital treatment. He was convicted of assault, ordered to pay his ex-wife £150 in compensation — and £818 to the owner of the BMW.

No one saw it coming. Everyone — including the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) — expected at least some of the recall campaigns against 24 of its lawmakers and Hsinchu Mayor Ann Kao (高虹安) to succeed. Underground gamblers reportedly expected between five and eight lawmakers to lose their jobs. All of this analysis made sense, but contained a fatal flaw. The record of the recall campaigns, the collapse of the KMT-led recalls, and polling data all pointed to enthusiastic high turnout in support of the recall campaigns, and that those against the recalls were unenthusiastic and far less likely to vote. That

Behind a car repair business on a nondescript Thai street are the cherished pets of a rising TikTok animal influencer: two lions and a 200-kilogram lion-tiger hybrid called “Big George.” Lion ownership is legal in Thailand, and Tharnuwarht Plengkemratch is an enthusiastic advocate, posting updates on his feline companions to nearly three million followers. “They’re playful and affectionate, just like dogs or cats,” he said from inside their cage complex at his home in the northern city of Chiang Mai. Thailand’s captive lion population has exploded in recent years, with nearly 500 registered in zoos, breeding farms, petting cafes and homes. Experts warn the

A couple of weeks ago the parties aligned with the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), voted in the legislature to eliminate the subsidy that enables Taiwan Power Co (Taipower) to keep up with its burgeoning debt, and instead pay for universal cash handouts worth NT$10,000. The subsidy would have been NT$100 billion, while the cash handout had a budget of NT$235 billion. The bill mandates that the cash payments must be completed by Oct. 31 of this year. The changes were part of the overall NT$545 billion budget approved

The unexpected collapse of the recall campaigns is being viewed through many lenses, most of them skewed and self-absorbed. The international media unsurprisingly focuses on what they perceive as the message that Taiwanese voters were sending in the failure of the mass recall, especially to China, the US and to friendly Western nations. This made some sense prior to early last month. One of the main arguments used by recall campaigners for recalling Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers was that they were too pro-China, and by extension not to be trusted with defending the nation. Also by extension, that argument could be