Of the various renewable energy sources that Taiwan has embraced in recent years, none is more important than solar. The government aims to install 20 GW of photovoltaic (PV) capacity by 2025, triple the target for wind energy and all other renewables combined. If achieved, that will represent more than a third of Taiwan’s power-generating capacity.

Once they’ve been manufactured and installed, solar cells convert sunlight into electricity without producing carbon emissions. Nor do they cause air, water or noise pollution.

There’s just one problem. Like conventional power plants, PV modules don’t last forever. While it’s true that some arrays set up in other countries in the early 1980s are still going strong, solar-energy systems in Taiwan are exposed to typhoons and tremors, as well as strong ultraviolet light that causes the cells themselves to degrade.

Photo courtesy of Chaojhou Township Administrative Office

It’s unclear how long the PV systems installed across Taiwan in recent years are likely to function. However, industry sources, researchers and authorities predict that most PV modules will be decommissioned within 25 years of connection to the grid. According to the Web site of the Circular Taiwan Network — an NGO which names climate change, dependence on imported resources and pollution as major threats facing the country — this means that Taiwan will produce at least 1.4 million tonnes of discarded solar panels by 2050.

In theory, the country’s waste-processing systems can handle such quantities. But old panels aren’t suitable for incineration, and dumping them in landfills raises the risk of metals like cadmium, copper, lead and selenium leaching into the soil. A literature review by Indian researchers, published in Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews in March 2020, concluded that not enough attention has been paid to the possibility that carcinogenic pollutants might be released if modules aren’t properly disassembled.

Furthermore, if the materials inside old solar panels can be reclaimed and turned into new solar panels, the lifetime carbon emissions of new panels will be much lower.

Photo courtesy of ITRI

On Nov. 8, 2018, the Liberty Times (Chinese-language sister paper of the Taipei Times) reported that local government employees were removing 800-odd typhoon-damaged solar panels that had been dumped beside a fish farm in Changhua County’s Dacheng Township (大城). The authorities were also trying to identify the individual or company responsible, as improper disposal of industrial waste can result in a fine of up to NT$3 million.

A typical PV panel weighs around 18kg, three quarters of which is glass. The aluminum frame is at least 10 percent of the weight, while the solar cells themselves — made of monocrystalline, polycrystalline, or thin-film silicon wafers from 0.1mm to 0.5mm thick — represent less than 4 percent. Plastics account for most of the rest.

Since Feb. 2019, the Environmental Protection Administration (EPA) has been working with the Ministry of Economic Affairs’ Bureau of Energy to collect a one-off recycling fee for PV modules of NT$1,000 per KW capacity, payable when the panels are sold.

Photo: Chen Kuan-pei, Taipei Times

Like the EPA-administered fund that supports the PET/PP recycling ecosystem, this money is being used to subsidize the collection and processing of solar panels. It’s official recognition that, even though almost every part of an unwanted PV system can be recycled — the aluminum frame and copper conductive tape in each panel, as well as the silver glue and lead-tin solder that adhere to the tape, for instance, can be turned into easy-to-sell commodities — the value of retrievable materials isn’t enough to cover the cost of separating them.

Moreover, current disposal procedures are far from ideal. An EPA Web page about solar-panel recycling from August last year says that the two local facilities licensed to deal with waste PV modules, “mainly use a mechanical process to crush the panels and then send the fragments to Japan to be used as slagging agents in copper smelters.”

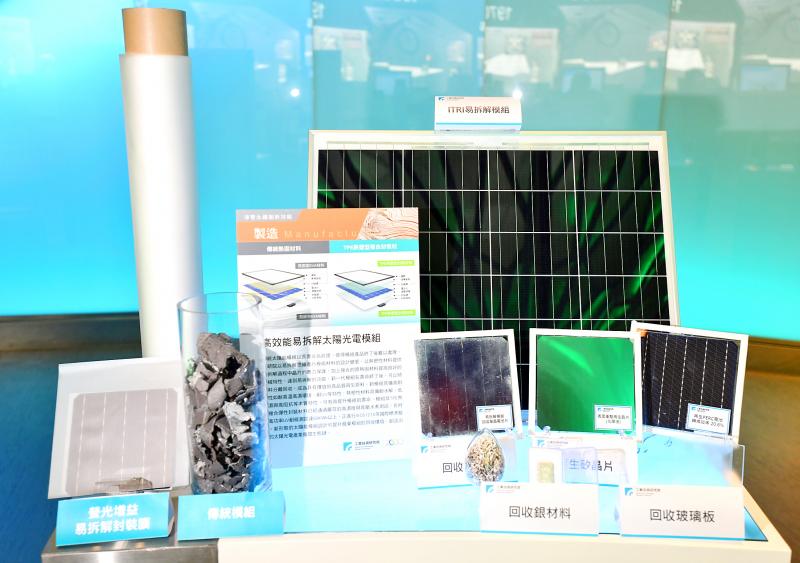

Taiwan has one of the world’s highest glass recycling rates, but crushing panels results in low-purity glass pellets. Glass sheets that can be removed intact are more valuable — and this is something Taiwan’s Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) has included in its efforts to redesign PV modules so that recycling them is easier.

Photo courtesy of UJGIGA

ITRI scientists also claim to have discovered a manufacturing technique that could greatly increase the rate at which silicon wafers are reclaimed intact from old panels.

Successfully retrieving wafers has long been difficult, because solar-panel makers use ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA) or polyolefin (PO) to encase solar cells.

As ITRI’s Liu Yi-chun (劉怡君) explained in September last year during an international Webinar on PV panels (“Approaching to Green More: Easy-Dismantled PV Module”), when pyrolysis (heating at high temperatures) is applied to melt a panel’s already-dismantled backpane, bubbles appear in the EVA/PO. There’s no way for these bubbles to escape, so they end up rupturing the wafers.

ITRI researchers have found that, by adding an extra layer of thermoplastic elastomer plastic (TPE) around the solar cells, they can avoid this problem.

According to Liu, pyrolysis and chemically processing one of ITRI’s easy-to-recycle PV modules generates lower carbon emissions than crushing and sorting a standard commercial PV panel. What’s more, she stressed, the former approach produces reclaimed materials of far greater value.

Recycled silicon wafers that can be reused by PV-module manufacturers would be an especially significant step toward a greener circular economy. According to the ITRI Web page for the September event, virgin silicon wafers are refined from silicon ore and undergo complex manufacturing processes, so their environmental impact is considerable. The carbon footprint of recycled wafers, by contrast, is just 17 percent of that of virgin silicon wafers.

Unfortunately, it’s doesn’t seem likely that modules optimized for dismantling and recycling will be mass-produced in the near future.

Asked if any manufacturers plan to bring easy-to-recycle PV modules that incorporate ITRI’s innovations to market anytime soon, the institute said those technologies will be made available once trials have been completed.

The Taipei Times reached out to four Taiwan-based makers of PV equipment, asking if they intend to revise the design of their modules, so as to make recycling them easier. None of the companies responded.

Fortunately, other local scientists are working to enhance recycling processes for PV modules as they’re currently configured.

A research group led by Fu Yaw-shyan (傅耀賢), a professor in National University of Tainan’s Department of Greenergy Technology, began by using chemical decomposition to separate the various materials within each panel. This method was effective, but Fu’s team decided not to pursue it, because the solvents used are unkind to the environment.

They then looked in physical separating the different layers within a module by planing. Initially, the heat generated by this process caused the adhesives within the test panels to soften, gumming up the machinery. Fortunately, Taiwan is a global leader in precision machining. By drawing on expertise in the private sector, Fu’s team were able to solve this problem.

Unlike ITRI’s design innovations, the system Fu and his colleagues are endeavoring to refine doesn’t result in glass sheets ready for reuse or intact silicon wafers. On the plus side, by avoiding pyrolysis, it shouldn’t yield compounds which, if handled improperly, might harm human or environmental health.

According to a report in July last year in Taiwan Panorama, Fu’s team believe their PV-module recycling system can be fully automated and fitted inside a 40-foot cargo container. By opening the door to worldwide deployment, this advance could be a significant victory in the war against e-waste.

Steven Crook, the author or co-author of four books about Taiwan, has been following environmental issues since he arrived in the country in 1991. He drives a hybrid and carries his own chopsticks. The views expressed here are his own.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.