Beijing high schooler Chen Zhichu used to spend 30 minutes a day boosting actor Sean Xiao (肖戰) online as one of a legion of superfans, before the practice fell foul of the government for promoting “unhealthy values.”

State regulations last month banned “irrational star-chasing” — online celebrity rankings, fundraising and other tools used by China’s fandoms to get their idols trending on social media — in the latest of a series of crackdowns across Chinese society. Known for his androgynous good looks, Xiao earned legions of devoted, mostly female fans through his role in the 2019 fantasy drama The Untamed, and has over 29 million followers on Weibo alone.

“I used to upvote posts in his Weibo fan forum and buy products he promoted,” Chen, 16, said in a busy downtown shopping district. “It was pretty exhausting trying to keep him trending at number one every day.”

Photo: AFP

Fans power China’s lucrative idol economy, previously forecast by state media to be worth 140 billion yuan (US$21.6 billion) by next year.

In a country where young people have few other means of influencing public life, full-time fan content creators — dubbed zhanjie (站姐) or “station sisters” — can propel a star’s rise from obscurity by creating viral images of them. Critics say fan culture is an exploitative industry aimed at profiting from minors, built on artificially inflated social media engagement — something the government wants to eliminate through the new regulations.

Authorities say the new rules are needed to curb excessive aspects of fan culture, including cyberbullying, stalking, doxxing and bitter online wars between fandoms.

Photo: AFP

But many fans say they derive pleasure from seeing their idols flourish and have found a sense of community from the shared online space.

MORALITY CRACKDOWN

Communist authorities are also worried about idols for another reason: their ability to mobilize fan armies at a moment’s notice, often dominating social media for days.

Photo: AFP

“It’s the beginnings of a mass movement and that is what the government doesn’t want,” said a social studies professor at a Chinese university who did not wish to be named.

Multiple crackdowns have swept the tech, education and showbiz sectors in recent months, as authorities increasingly target the rich and powerful in a push for greater socioeconomic equality.

But it is also partly to instil “healthy,” government-sanctioned societal values in young people, so they are less influenced by wayward celebrities.

“Chinese youth lack other types of idols,” said Fang Kecheng, communications professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. “It’s very hard for them to have other means of civic participation [such as activism].”

China’s broadcast regulator last month banned performers with “lapsed morals” and “incorrect political views,” as well as what it termed “sissy men” — an androgynous aesthetic popularized by Korean boybands, and imitated by male Chinese idols like Xiao. Experts read the latter as a sign of Beijing’s increasing discomfort with alternative forms of masculinity at a time of falling birth rates and rising nationalism, as films with macho, military heroes are promoted by the state.

‘NECESSARY GROWTH STAGE’

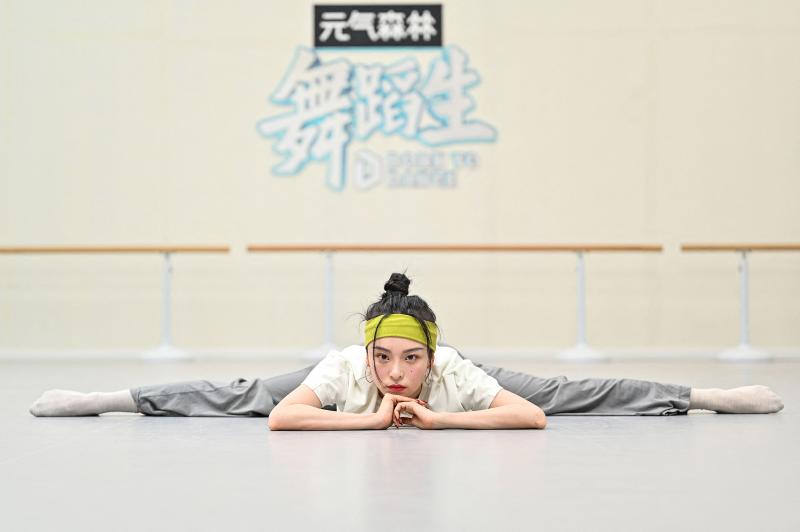

For one idol-in-waiting in Shanghai, the crackdown on celebrity culture is a chance for an industry reset. Regulation “is a growth stage that the industry needs to go through” 26-year-old Li Chengxi (李丞汐) said during rehearsals for a reality dance competition filming in Nantong, east China.

Li has been an avid dancer and actress since childhood. After graduating from the elite Peking University, she tried to make it as an entertainer, starring in a few films and idol talent shows — a genre now banned by broadcast regulators. Still, she remains unfazed by the potential for state rules to cramp her progress.

“When huge waves break ashore, the gold left behind will shine even brighter,” she said.

Chinese entertainers wanting mainstream success have little choice but to agree with the state, whose disapproval can ultimately sink their careers.

While Li has over 200,000 followers on social media, it’s far from viral superstardom. And for now, Chinese superfans are keeping a low profile both on and offline.

“After this round of clean-ups, there will still be fan activities, but maybe fewer than before,” said one Beijing-based fan in her twenties surnamed Geng.

“Everyone’s watching and waiting.”

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.

It’s a bold filmmaking choice to have a countdown clock on the screen for most of your movie. In the best-case scenario for a movie like Mercy, in which a Los Angeles detective has to prove his innocence to an artificial intelligence judge within said time limit, it heightens the tension. Who hasn’t gotten sweaty palms in, say, a Mission: Impossible movie when the bomb is ticking down and Tom Cruise still hasn’t cleared the building? Why not just extend it for the duration? Perhaps in a better movie it might have worked. Sadly in Mercy, it’s an ever-present reminder of just