“That all those who knew him should write about him,” Borges wrote of the protagonist Ireneo Funes in his story Funes the Memorious, “seems to me a felicitous idea.” Certainly those who knew Borges, even in passing, thought it was a felicitous idea to write about him. Fifty years ago, it seemed that a trip to Buenos Aires wasn’t complete without a stopover at his sixth-floor Calle Maipu apartment, which he shared with his mother.

Both Alberto Manguel and Paul Theroux have written about reading to the blind genius in his living room. VS Naipaul, in The Return of Eva Peron, found Borges to be “curiously colonial,” insulated from the violence and disorder in his country. When Mario Vargas Llosa visited in 1981, he noticed that Borges had kept his mother’s bedroom intact, with a lilac dress ready on the bed, even though she had died six years before.

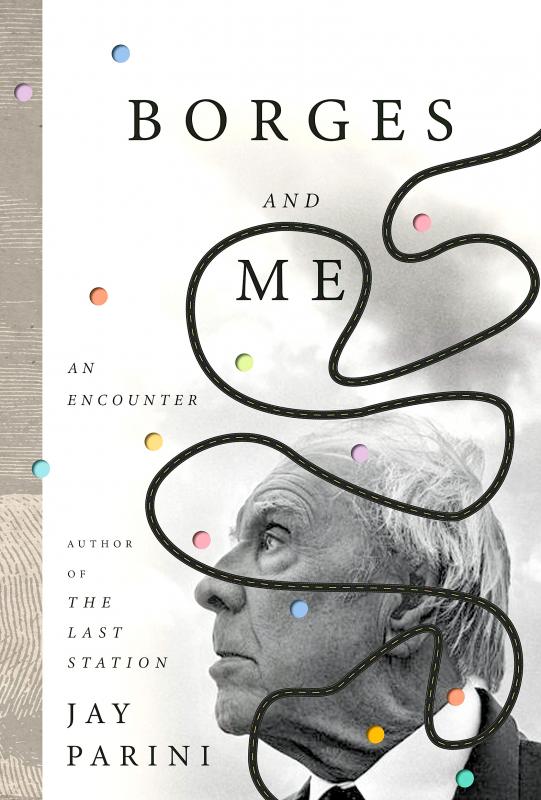

Jay Parini’s “encounter” happened far from Argentina. He claims to have met Borges in Scotland, while doing his PhD at St Andrews. Parini was close to the poet Alastair Reid, who lived nearby and wrote regularly for the New Yorker: Reid was also one of Borges’s English translators. During Borges’s visit in 1970, Reid was called away for a few days to London. Parini was asked to look after the guest, and the two of them apparently set out on an impromptu journey across the Highlands. Borges offered to bear all costs, while Parini was tasked with both driving and describing aloud everything he saw en route.

“Description is revelation,” Borges told him.

Borges even christened the car Rocinante and fancied their getaway as Don Quixote and Sancho Panza on a Scottish literary pilgrimage. They stayed at the Crusoe hotel in Lower Largo, where Borges tasted a pint of Export — by stirring the foam with his fingers and licking them — for the first time in his life.

In Dunfermline, he licked the spine of a Walter Scott novel inside a library. In the Cairngorm mountains, he slipped down a slope while screaming out lines from King Lear in a thunderstorm. At Loch Ness, he fell out of a boat while trying to recite Beowulf in the middle of the lake. In Inverness, he set out to meet one Mr Singleton, with whom he had been corresponding for years on Anglo-Saxon riddles. But when Parini called the number on the slip of paper Borges handed to him, they discovered that Mr Singleton lived in Inverness, New Zealand.

Did it really happen? Parini says in the afterword that the events are true, though he calls the book a “novelized memoir” and makes modish allusions to “autofiction.” Stories, however, seem real not because of their veracity to facts, but the vitality with which they are told, and it is in the telling that Borges and Me seems least persuasive.

Borges is alternately portrayed as the madman artist type and an erratic, cane-wielding uncle who keeps having mishaps everywhere and needs to use the bathroom every few minutes. Parini’s inner thoughts seldom rise to the occasion — when he is introduced to Borges, all he can wonder about is “if those who can’t see can sense more than the rest of us” — and as a narrator he can’t help but always spell out the subtext, which suggests a lack of confidence in his memories and fabrications.

Parini isn’t above reminding the reader that Scotland is the birthplace of Robert Burns and dropping the shopworn Auden quote about poetry making “nothing happen.” It is possible to enjoy the story if you are willing to ignore the one-note conversations throughout the trip and believe that the hijinks of the plot can suffice as evidence of a bond between master and apprentice.

Parini’s American backstory feels more credible. He has moved across the Atlantic to avoid being conscripted to the war in Vietnam. At 22, he wants to escape the humdrum fate of his middle-class parents in Scranton, Pennsylvania. Every other week he receives letters from his mother (“you should be so careful of Scottish girls”), the draft board and his best friend, Billy, who has signed up for combat: “High is the only place to be in ’Nam.”

His father gets the best sentence in the book — “The sidewalks of his mind were strewn with banana peels” — and Billy’s experiences contrast powerfully with Parini’s “girl troubles” on campus.

Borges remains a side character in Parini’s trajectory of getting the girl and finding a suitable topic for his graduate thesis. Parini tries to pad up the thinness by having the old man mouth lines from his greatest hits: Funes, the Memorious, Borges and I, The Library of Babel. Driving through the hills in an old Morris Minor, Parini begins to realize that “the connection between words and things obviously mattered.” If only he were able to cover up the seams.

US President Donald Trump may have hoped for an impromptu talk with his old friend Kim Jong-un during a recent trip to Asia, but analysts say the increasingly emboldened North Korean despot had few good reasons to join the photo-op. Trump sent repeated overtures to Kim during his barnstorming tour of Asia, saying he was “100 percent” open to a meeting and even bucking decades of US policy by conceding that North Korea was “sort of a nuclear power.” But Pyongyang kept mum on the invitation, instead firing off missiles and sending its foreign minister to Russia and Belarus, with whom it

When Taiwan was battered by storms this summer, the only crumb of comfort I could take was knowing that some advice I’d drafted several weeks earlier had been correct. Regarding the Southern Cross-Island Highway (南橫公路), a spectacular high-elevation route connecting Taiwan’s southwest with the country’s southeast, I’d written: “The precarious existence of this road cannot be overstated; those hoping to drive or ride all the way across should have a backup plan.” As this article was going to press, the middle section of the highway, between Meishankou (梅山口) in Kaohsiung and Siangyang (向陽) in Taitung County, was still closed to outsiders

Many people noticed the flood of pro-China propaganda across a number of venues in recent weeks that looks like a coordinated assault on US Taiwan policy. It does look like an effort intended to influence the US before the meeting between US President Donald Trump and Chinese dictator Xi Jinping (習近平) over the weekend. Jennifer Kavanagh’s piece in the New York Times in September appears to be the opening strike of the current campaign. She followed up last week in the Lowy Interpreter, blaming the US for causing the PRC to escalate in the Philippines and Taiwan, saying that as

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has a dystopian, radical and dangerous conception of itself. Few are aware of this very fundamental difference between how they view power and how the rest of the world does. Even those of us who have lived in China sometimes fall back into the trap of viewing it through the lens of the power relationships common throughout the rest of the world, instead of understanding the CCP as it conceives of itself. Broadly speaking, the concepts of the people, race, culture, civilization, nation, government and religion are separate, though often overlapping and intertwined. A government