For the last two decades, there has been a growing chorus of think pieces arguing that the US should clarify its position on Taiwan and end its policy of “strategic ambiguity,” its refusal to announce an official position stating clearly whether and under what conditions it would defend Taiwan.

Like antibodies rushing to defend a breach in the skin, such articles then attract wave after wave of essays contending that ending strategic ambiguity is a bad idea.

PRECEDENTS

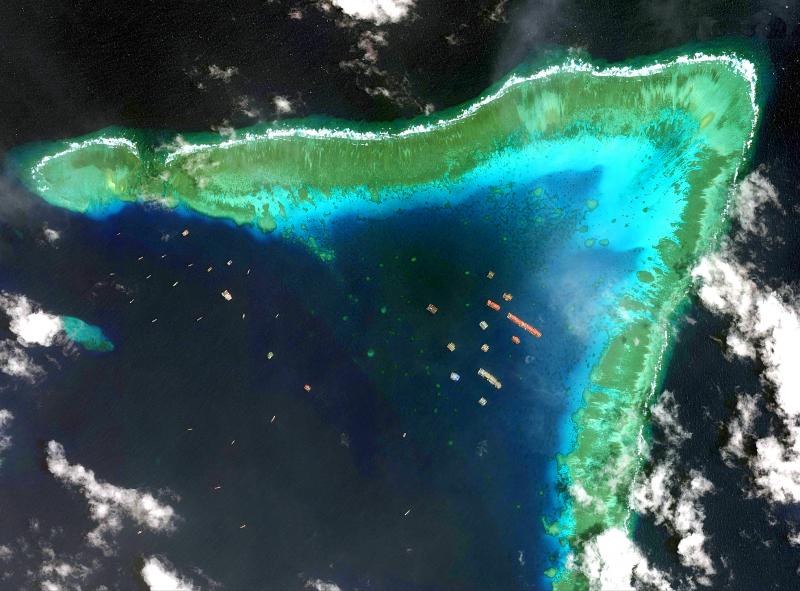

Photo: Maxar Technologies via AFP

Yet, just off Taiwan are two cases that can shed light on the problems at the heart of strategic ambiguity, the Philippines and Japan. Farther off, the subcontinent offers several others, including India, Nepal and Bhutan.

If observers wish to see what might happen when the US commitment is “clear,” they need merely consider the cases of the Philippines and Japan, both of which have mutual defense treaties with the US that compel it to come to their aid if attacked.

At present, China occupies features in the South China Sea that indisputably belong to the Philippines, such as Scarborough Shoal (Huangyan Island, 黃岩島, also claimed by Taiwan). It uses both fishing boats and paramilitary vessels to carry out these activities. While the US has made noise, Chinese boats remain at Scarborough and elsewhere in the South China Sea.

Photo: Reuters

This occupation, though overt theft, has not triggered a US military response.

Similarly, the Diaoyutai Islands (釣魚台, known as the Senkaku Islands in Japan, also claimed by Taiwan and China), Japanese since the late 19th century, have been the site of numerous incursions by Chinese boats in recent years. The US has publicly stated that it includes the Senkakus in its mutual defense treaty with Tokyo, and years ago, even carried out wargames there with Japanese defense forces.

This clarity — repeated on a regular basis by US officials — has not deterred China from pushing its ships and aircraft into the area, and then withdrawing them.

Indeed, looking at the Philippines and Japanese cases, it is not difficult to conclude that US clarity actually makes it easier for China to carry out its provocative acts of aggression, because the treaty lets China know what it can and cannot do. It also enables China to locate and then define the boundaries of US action via constant testing of them.

Beijing is carrying out some of the same activities at the moment against Taiwan, testing Taiwan with planes, but more importantly, with sand dredgers off Matsu’s coast. This has forced Taiwan to conduct round-the-clock patrols of the area, even as Matsu’s communications cables and tourism are disrupted by the Chinese dredgers. China deploys hundreds of dredgers, against less than a dozen Coast Guard vessels from Taiwan.

Yet, it has not physically occupied any features that are indisputably Taiwanese, such as islands in Penghu. Nor have the dredgers appeared elsewhere off Taiwan-controlled waters. When Taiwan Coast Guard ships appear, the dredgers generally withdraw, to return when they are gone.

Beijing does not know how the US will react to more aggressive moves against the possessions of Taiwan. Perhaps that is encouraging restraint.

Perhaps it is merely a matter of time.

Those who argue that the US should end its policy of strategic ambiguity should take a hard look at Philippines and Japan, and the US (non-)response to Chinese incursions.

FICKLE US POLICY?

They should also consider the fickleness of US policy, shifting from year to year and administration to administration. Imagine, for example, if the hopelessly weak and compromised administration of president Barack Obama had ended strategic ambiguity. What definition of US policy would we now be constrained by?

Recently many observers have been cheered by strong US statements about its relationship with Taiwan. Indeed, some officials have even said that Taiwan is no longer viewed as a problem by the US.

For example, a State Department official said: “Taiwan is not looked at as a problem anymore, but as a success story.” Sorry, my bad. That was from 2002.

Meanwhile, China is also pursuing policies of expansion in the Himalayas, a major flashpoint. The seizure of land features belonging to India brought a sharp response from New Delhi. China is certain that India will react vigorously, yet it continues its expansionist policies.

It also has seized land belonging to Nepal and to Bhutan. Surveys done last year by the government of Nepal indicated that land in seven different districts had been seized by China. Similarly, this year it was revealed that China had been constructing roads, buildings and military facilities in a valley belonging to Bhutan since 2015.

Nepal, Bhutan, and Philippines are militarily weak, and can do little against Chinese aggression. India and Japan are much stronger.

None of this array of postures and strengths seems to mean much in the face of Chinese aggression. China presses on them all, weak or strong, allied or alone, carefully but persistently.

Commentators often forget that another purpose of strategic ambiguity is to deter Taipei, though this aspect of the policy has been less explored in recent years. Strategic ambiguity thus deters both sides, at least in the US view.

PRETEXT OF CIVIL UNREST

It is not difficult to imagine how, if the US had a clear policy of intervention in the case of Chinese attack, the situation could be exploited by a Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) president. If a KMT president could incite “civil unrest” in Taiwan through some absurdly pro-China move, like China-friendly former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) did with the two trade and services agreements, what is to stop him from calling for People’s Liberation Army troops to “restore order?”

What if a KMT president were to invite Chinese troops in to help with typhoon relief? How would Washington react, if its red lines had already been drawn elsewhere?

At the moment, strategic ambiguity is important not only because China does not know what the US would do in the case of an invasion, but also because Beijing does not know where the boundaries of the US response are located. Literally anything from a full-scale invasion to a White House fit of pique could trigger an armed response from Washington.

Yet, what the incursions into others’ territories in the Himalayas, in the South China and in the Senkakus suggest is that, in the long term, “strategic ambiguity” is simply going to become irrelevant.

Beijing will do what Beijing will do: “salami slicing” against its opponents irrespective of their policies or positions, their strengths or weaknesses. The current debate over “strategic ambiguity” in US circles signals, not the coming of a shift in the US position, but its rapidly growing irrelevance.

Notes from Central Taiwan is a column written by long-term resident Michael Turton, who provides incisive commentary informed by three decades of living in and writing about his adoptive country. The views expressed here are his own.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)