From the Sunflower Movement to national referendums to indigenous rights, participatory budgeting and the recall of former Kaohsiung mayor Han Kuo-yu (韓國瑜), active and vibrant civil participation has continuously made an impact on the government’s policies in the past decade.

In political science terms, this is called “deliberative democracy,” where political decisions are made according to fair and informed discussions between the stakeholders involved. It doesn’t always work as it should, but at least it gives citizens an opportunity to engage in policymaking beyond just participating in elections.

Author Fan Mei-fang (范玫芳), professor at National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University and researcher at National Taiwan University’s Risk Society and Policy Research Center (風險社會與政策研究中心), offers much insight into the multifaceted and complex development of deliberative democracy in Taiwan, showing how the country can serve as a model for such governance. As one of the few free and open societies in Asia, the nation is indeed quite a unique case, and more countries should learn about how its vibrant civil society actually gets to make a difference.

However, the book is filled with political theory and academic terms, and the prose is quite dry and impersonal even in the qualitative sections. It will mostly appeal to democracy scholars or those with a deep interest in Taiwan.

For those who decide to tackle the text, however, it is very thorough and systematic and does a good job explaining the various mechanisms and platforms that deliberative democracy manifests in Taiwan and its significance toward creating a more equal and open society. Fan provides an elucidating overview of a topic that most people otherwise hear about through individual events or academic specializations, though the reader must already be well-versed in Taiwanese politics and recent history.

Fan appears to be quite active in the field. She has worked on the nation’s nuclear waste issue for more than a decade, and helped conduct a citizen conference on the issue in 2010. She is also on the steering committee of various deliberative forums such as the national electronic identification cards (eID) open policy workshop as well as the Taipei City participatory budgeting government-academia alliance. She has worked with public budgeting district offices and helped train graduate students to serve as facilitators in resident assemblies.

Fan spent five months in 2018 at the Center for Deliberative Democracy and Global Governance at the University of Canberra in Australia, and the book draws significantly from the work of the institute’s lead professor, John Dryzek.

Dryzek writes in the foreword that “it is rare indeed that anyone takes on a whole country in deliberative system terms,” adding that to his knowledge, Fan’s work is the “first book-length treatment that interprets the whole political system of a country as a potentially deliberative system.”

While some of Taiwan’s innovations are drawn from the West, others, such as the Citizen Congress Watch, are original innovations that the nation should get more recognition for.

“There is much that the world can and should learn from Taiwan when it comes to deliberative democratic possibilities,” Dryzek writes.

These possibilities emerge and take shape in myriad ways, starting from the consensus conferences on national health insurance in 2002 to digital democracy, which the current government has embraced. The common thread is that people’s voices are heard and actually considered, and the government is held more accountable for their actions and pushed toward institutional reform and transformation.

The first part of the book provides a comprehensive overview of the common themes and development of deliberative democracy in Taiwan, while the second part closely examines three case studies where civic engagement made a difference: the nuclear waste storage issue, the Asia Cement Corp (亞洲水泥) versus indigenous land rights controversy and the Taipei City Government’s active participatory budgeting initiative.

Throughout the book, Fan delves into complex interactions between various groups that go beyond the simple citizen participation. Deliberative efforts are made on multiple levels in varying scales in these case studies, and it’s not an easy task to contextualize and summarize them in a meaningful way. Fan is able to do this and that’s what makes the book worth a look.

Although Fan points out various flaws and problems, one can’t help but feel that the book still paints quite a rosy picture of the nation’s political process. Taiwan’s achievements in its democracy and open society should be lauded, but things are far from perfect and it would have been interesting to see more criticism in areas where the government isn’t doing well.

Also, the book focuses on the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) or third party efforts, noting that deliberative democracy declined when the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) took power in 2008 (although they still had to rely on it).

This reviewer would be curious to learn more about this shift and how to install safeguards to prevent such a drop from happening again.

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not

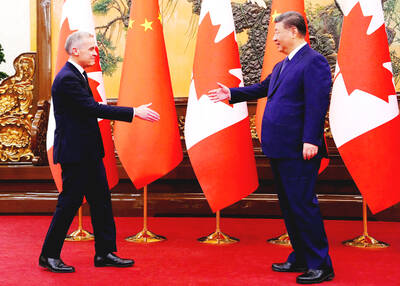

Britain’s Keir Starmer is the latest Western leader to thaw trade ties with China in a shift analysts say is driven by US tariff pressure and unease over US President Donald Trump’s volatile policy playbook. The prime minister’s Beijing visit this week to promote “pragmatic” co-operation comes on the heels of advances from the leaders of Canada, Ireland, France and Finland. Most were making the trip for the first time in years to refresh their partnership with the world’s second-largest economy. “There is a veritable race among European heads of government to meet with (Chinese leader) Xi Jinping (習近平),” said Hosuk Lee-Makiyama, director