This book details the experiences of four would-be escapees fleeing Shanghai in advance of the arrival there of the Chinese Communist Party-controlled People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in 1949. One of them is headed for Taiwan, but even at the start of the book Taiwan has more attention than this might suggest. There are no records in China of any exodus, for example, only accounts published in Taiwan.

On the pier prior to embarkation, one character, destined for the US, meets someone in a hurry to get a car onboard a ship heading for Taiwan for the benefit of his brother, who is there already. And lastly it’s recorded how the Jiangya, a ship packed with escapees bound for Taiwan, exploded and sunk in December 1948 in a heavily mined stretch of the Huangpu River connecting Shanghai to the sea. Fatalities had been far in excess of those on the Titanic. Another Taiwan-bound vessel, the Taiping, was sunk a few weeks later.

On May 25, 1949 the PLA takes Shanghai. Prior to this, between 1.3 million and two million “mainlanders” descend on Taiwan’s nine million population.

The author begins her main narrative by introducing us to three children, Benny, Ho and Bing, the first two from prosperous families, the last from a less prosperous one, but all living in Shanghai in the 1930s. Bing is the young woman who is first seen at the start of the story as she boards a liner for America. The narration of their young lives gives the author an opportunity to fill us in on a swathe of Chinese history of the period.

But there’s a fourth child, Annuo, younger than the others. Two of the others make it to the US, though Benny remains in China. Annuo, by contrast, is eventually all set to go to Taiwan.

Annuo’s mother is a qualified doctor, but her father is in secret fighter for the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). He quickly moves to the Chinese interior and twice the family move out of Shanghai to join him. Back in the city, however, names have to be changed so as to hide from the Japanese any connection with him. The battle in this period (the early 1940s) is between China, led by Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石), and Japan. When the defeat of Japan is announced, however, KMT strongholds, of which Shanghai became one, have nothing to fear apart from the distant communists.

After the war ended, Annuo and her mother (plus a brother and a sister) are sent to live in Hangzhou, a lake-side city so attractive that even Chiang’s eldest son, Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國), opts to move there.

The PLA is not to remain distant for long, however, and many of the more prosperous Shanghainese are planning to leave. But where to? Annuo’s father decides on Taiwan, so after a ride to Shanghai on an overcrowded train the family flies to Keelung on a military cargo aircraft, also overcrowded.

“We have an obligation to teach the Taiwanese how to be Chinese again,” somebody says.

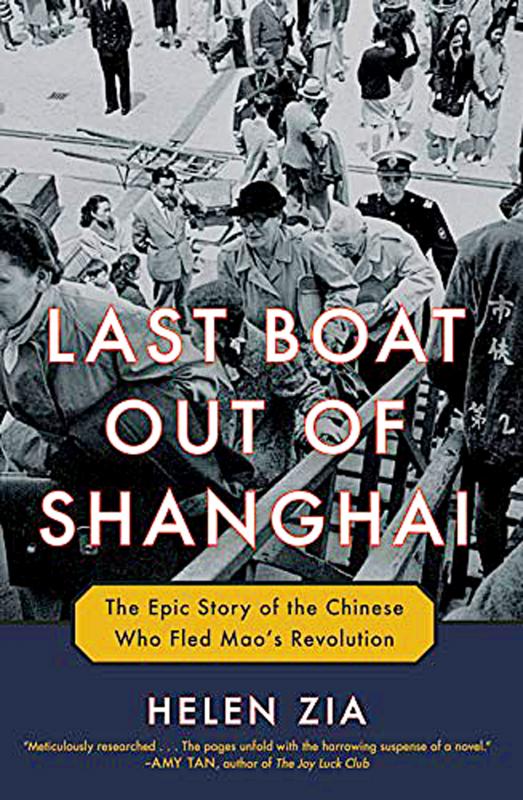

It’s important to understand that all these characters are real people. This is not a work of fiction, but of extensively researched fact. Photographs of all the main protagonists are included throughout.

In Taipei, Annuo’s family is housed, to their annoyance, in a Japanese-style building with tatami mats and paper doors. Annuo, however, succeeds in gaining a place at the prestigious Taipei First Girls’ High School, and her father eventually gets a job in charge of fisheries with an American-owned company.

Meanwhile, Bing and Ho settle into life in the US. Benny, however, remains in China and suffers greatly during the Cultural Revolution. Finally he too gets to the US after a special dispensation following the Tiananmen Square events of 1989.

Annuo easily obtains entrance to National Taiwan University (NTU), majoring in law like her father before her. From there she applies for graduate school in the US and receives admission to study journalism at a university in Portland, Oregon. Once there, she takes the Western name of Annabel.

After graduation, she heads to New York and finds a job in the rights and permissions department of a company called Scholastic Magazines. Proficient now in English, and with even a Shanghai restaurant nearby, Annuo is close to realizing her dreams.

The main attraction of Last Boat out of Shanghai is that it focuses on refugees and immigrants. Given the current hostility to such people, this is a huge plus. Comparisons with the refugees today to Europe from countries like Syria are inescapable.

Back in those days there were very distinguished immigrants to the US from Germany — Albert Einstein, Thomas Mann and Walter Gropius, for example. The Shanghaiese, however, often found life in a new country harder and sometimes had to move on following anti-Chinese developments, in Malaysia and Indonesia for instance.

Annuo eventually marries a physicist, Sam, and, after he finds work with IBM, she accepts a job at Reader’s Digest. After Sam is appointed a professor at Iowa State University, Annuo starts writing seriously in her own right, beginning with the Des Moines Register’s Sunday magazine. Her stories about life as a Chinese migrant in the US are serialized in Taiwan and she becomes a regular essayist for World Journal, a widely-read American Chinese newspaper. She eventually manages to bring her parents and siblings to join her in the US.

The author, Helen Zia (謝漢蘭), states that this book is the result of hundreds of hours of interviews with the four main protagonists, plus many other Shanghainese migrants now living in the US.

This is a long, attractively written and very comprehensive book. Reading it will inform you of 20 years and more of Chinese history. During Annuo’s time at NTU, for instance, we learn a lot about the Korean War and Washington’s fluctuating policies towards Taiwan.

Zia recalls a relative saying she was on the proverbial “last boat out of Shanghai,” showing that Zia too has her roots in the city. It is only close to the book’s end that she reveals that she is in fact Bing’s daughter.

This is an extremely impressive book, massively researched yet narrated with the touch of a novelist. Readers are bound to be fascinated by it, and it’s highly recommended.

Taiwan can often feel woefully behind on global trends, from fashion to food, and influences can sometimes feel like the last on the metaphorical bandwagon. In the West, suddenly every burger is being smashed and honey has become “hot” and we’re all drinking orange wine. But it took a good while for a smash burger in Taipei to come across my radar. For the uninitiated, a smash burger is, well, a normal burger patty but smashed flat. Originally, I didn’t understand. Surely the best part of a burger is the thick patty with all the juiciness of the beef, the

The ultimate goal of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is the total and overwhelming domination of everything within the sphere of what it considers China and deems as theirs. All decision-making by the CCP must be understood through that lens. Any decision made is to entrench — or ideally expand that power. They are fiercely hostile to anything that weakens or compromises their control of “China.” By design, they will stop at nothing to ensure that there is no distinction between the CCP and the Chinese nation, people, culture, civilization, religion, economy, property, military or government — they are all subsidiary

This year’s Miss Universe in Thailand has been marred by ugly drama, with allegations of an insult to a beauty queen’s intellect, a walkout by pageant contestants and a tearful tantrum by the host. More than 120 women from across the world have gathered in Thailand, vying to be crowned Miss Universe in a contest considered one of the “big four” of global beauty pageants. But the runup has been dominated by the off-stage antics of the coiffed contestants and their Thai hosts, escalating into a feminist firestorm drawing the attention of Mexico’s president. On Tuesday, Mexican delegate Fatima Bosch staged a

Would you eat lab-grown chocolate? I requested a sample from California Cultured, a Sacramento-based company. Its chocolate, not yet commercially available, is made with techniques that have previously been used to synthesize other bioactive products like certain plant-derived pharmaceuticals for commercial sale. A few days later, it arrives. The morsel, barely bigger than a coffee bean, is supposed to be the flavor equivalent of a 70 percent to 80 percent dark chocolate. I tear open its sealed packet and a chocolatey aroma escapes — so far, so good. I pop it in my mouth. Slightly waxy and distinctly bitter, it boasts those bright,