Despite urban sprawl and industrialization, you needn’t travel far in Taiwan to see paddy fields. In 2019, rice was cultivated on 270,066 hectares of farmland — almost 7.5 percent of the country’s land area, and only very slightly less than in 1903.

Per hectare yields now often exceed 7,000kg, perhaps six times greater than in the mid-18th century. Much of this progress can be credited to the Sino-American Joint Commission on Rural Reconstruction (JCRR, 中國農村復興聯合委員會), which channeled US technology and fertilizers into local agriculture after 1949.

JCRR advised farmers to plow to a depth of 15cm instead of the usual 10cm, as deeper rooting increases the absorption of nutrients. When transplanting, farmers were urged to discard plants that weren’t obviously strong and healthy.

Photo: Steven Crook

According to a 1964 propaganda article, which boasted that per hectare yields in Yilan County had topped 4,600kg for the first time, “Use of fertilizer — both potassium and nitrogenous — was approximately doubled. More than three times as much money was spent on pesticides to make sure that insects didn’t reap the benefits of the increased growth. Spraying was carried out according to a synchronized, coordinated schedule.”

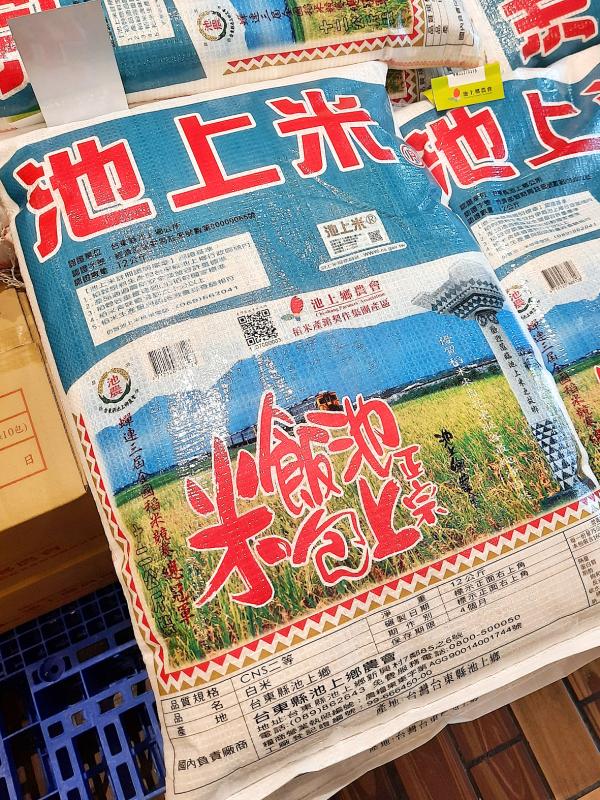

Since the 1895-1945 period of Japanese rule, one part of Taiwan has enjoyed a stellar reputation for its rice. Grain grown in Chihshang (池上) in Taitung was considered so excellent it was supplied to Japan’s royal household. These days, the township’s paddy fields aren’t just a source of a valuable commodity, but a tourist attraction in their own right.

My most recent wanderings through Chihshang began not at the famous and over-Instagrammed trees named in honor of actor Takeshi Kaneshiro (金城武) and singer Jolin Tsai (蔡依林), but 1.8km to the north, outside the Rice-Husking Mill of Chihshang Farmers Association (池上鄉農會觀光米廠).

Photo: Steven Crook

The fine dust blowing across Lisyue Road (力學路) made it obvious the mill was working. Trying not to breathe too deeply, I decided to look around the neighboring Taitung County Hakka Cultural Park (台東縣客家文化園區) before exploring the mill complex.

Outdoors, there’s a pond and some dumpy-yet-cute figurines. Indoors, one room displays a small collection of farm implements. For me, the highlight was in the other exhibition room, which housed a collection of black-and-white photos. I found these images, all taken in Hakka districts in East Taiwan between 1943 and 1970, quite engrossing.

The nitty-gritty of food production and industrial processes fascinates me, so I nosed my way around the mill. The complex isn’t set up with sightseers in mind, but I found a Chinese-only information panel that summarizes the five steps the farmers’ association takes to ensure the quality of Chihshang’s pesticide-free rice.

Photo: Steven Crook

After delivery to the mill, each batch of grain is tested for water content and husk thickness. Those two variables, along with the rice variety, are entered into a computer which controls machine-drying of the grain. The third stage is sorting by size and color; the bran may or may not be removed, depending on the wholesaler’s requirements.

To reduce the chances that inferior rice from elsewhere might be passed off as Chihshang grain, each package is given a sticker to show its authenticity. To keep the rice fresh, these sacks are then stored at a temperature no higher than 16 degrees Celsius.

Elsewhere, there’s an outline of the methods used by farmers before machines became common. Well into the 1960s, water buffalo dragged plows, powered pumps and transported grain.

Photo: Steven Crook

At the back of the mill, forklifts were shifting huge white bags of unhusked grain. Each weighed more than one tonne, a worker told me. Every bag bore a label with the name of the farmer, the date on which the rice had been delivered to the granary and the letters TGAP.

TGAP stands for Taiwan Good Agricultural Practice (台灣良好農業規範), a set of standard procedures which farmers are encouraged to follow to ensure the safety and quality of produce, while reducing the environmental consequences of pesticide and fertilizer use and eliminating risk factors. The Council of Agriculture has published more than 100 TAPs covering different crops, farmed fish and livestock.

The mill’s shop, not surprisingly, sells various types of rice and dozens of rice products, including rice-flour noodles and cookies.

Photo: Steven Crook

Chihshang’s economy isn’t as dependent on selling rice as it once was. This is a good thing, because yearly per capita consumption — which as recently as the 1970s exceeded 120kg — had by 2018 fallen to just 45kg. Nowadays, the average Taiwanese eats far less rice than the average resident of Japan or South Korea.

If it weren’t for the striking combination of paddy fields and foothills that surround Chihshang, it’s hard to imagine that so many visitors would spend time here. Swarms of tourists rent bicycles or e-bikes, but a determined walker could get from the railway station to what’s called Paradise Road (天堂之路), a scenic spot near the Takeshi Kaneshiro and Jolin Tsai trees, in a little over an hour.

Bringing a picnic is a good idea, as once you’re out amid the rice fields, there’s nowhere to get a meal. There’s even a scarcity of power lines and utility poles, because farmers believe the shadows they cast interfere with the natural growing cycle of rice.

Photo: Steven Crook

Another alternative to riding or tramping on an empty stomach is stopping by Dah Chi Bean Curd Sheet (大池豆皮店) at 39-2 Dapu Village (大埔村). No rice is served here, the key ingredient being imported soy. The fried soy sheets, soy milk (sweetened or unsweetened) and bean-curd pudding are all deliciously fresh.

That business opens at 7am and closes early in the afternoon. Getting to the area earlier or later won’t spoil your excursion. In my experience, at any moment between dawn and dusk, and in any season, you’re sure to find bewitching beauty in Chihshang’s agro-landscape.

Steven Crook has been writing about travel, culture and business in Taiwan since 1996. He is the author of Taiwan: The Bradt Travel Guide and co-author of A Culinary History of Taipei: Beyond Pork and Ponlai.

Wooden houses wedged between concrete, crumbling brick facades with roofs gaping to the sky, and tiled art deco buildings down narrow alleyways: Taichung Central District’s (中區) aging architecture reveals both the allure and reality of the old downtown. From Indigenous settlement to capital under Qing Dynasty rule through to Japanese colonization, Taichung’s Central District holds a long and layered history. The bygone beauty of its streets once earned it the nickname “Little Kyoto.” Since the late eighties, however, the shifting of economic and government centers westward signaled a gradual decline in the area’s evolving fortunes. With the regeneration of the once

Even by the standards of Ukraine’s International Legion, which comprises volunteers from over 55 countries, Han has an unusual backstory. Born in Taichung, he grew up in Costa Rica — then one of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies — where a relative worked for the embassy. After attending an American international high school in San Jose, Costa Rica’s capital, Han — who prefers to use only his given name for OPSEC (operations security) reasons — moved to the US in his teens. He attended Penn State University before returning to Taiwan to work in the semiconductor industry in Kaohsiung, where he

On May 2, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), at a meeting in support of Taipei city councilors at party headquarters, compared President William Lai (賴清德) to Hitler. Chu claimed that unlike any other democracy worldwide in history, no other leader was rooting out opposing parties like Lai and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). That his statements are wildly inaccurate was not the point. It was a rallying cry, not a history lesson. This was intentional to provoke the international diplomatic community into a response, which was promptly provided. Both the German and Israeli offices issued statements on Facebook

Perched on Thailand’s border with Myanmar, Arunothai is a dusty crossroads town, a nowheresville that could be the setting of some Southeast Asian spaghetti Western. Its main street is the final, dead-end section of the two-lane highway from Chiang Mai, Thailand’s second largest city 120kms south, and the heart of the kingdom’s mountainous north. At the town boundary, a Chinese-style arch capped with dragons also bears Thai script declaring fealty to Bangkok’s royal family: “Long live the King!” Further on, Chinese lanterns line the main street, and on the hillsides, courtyard homes sit among warrens of narrow, winding alleyways and