Dec 28 to Jan 3

Ciwang Iwal was spreading the gospel in the mountain village of Tausa when locals learned that the Japanese police were hunting her. According to many accounts, four Truku men took turns carrying her to Sanmin (三民) train station 10km away, where she caught a train to Hualien.

The Japanese were reluctant to prosecute Ciwang due to her role in mediating the conflict with her Truku brethren and authorities many years earlier, but they kept a close eye on her and tried to foil her actions. A cave next to the Ciwang Memorial Church near the visitor center to Taroko National Park is one of the hideouts where she used to preach, and converts who were caught often faced torture and beatings.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

But Ciwang was persistent, telling her followers that they should always be prepared to martyr themselves for their faith. The oppression of Aboriginal Christians ended with the defeat of the Japanese in 1945, and newly-arrived missionaries were surprised to find about 4,000 Truku Christians eager to be baptized.

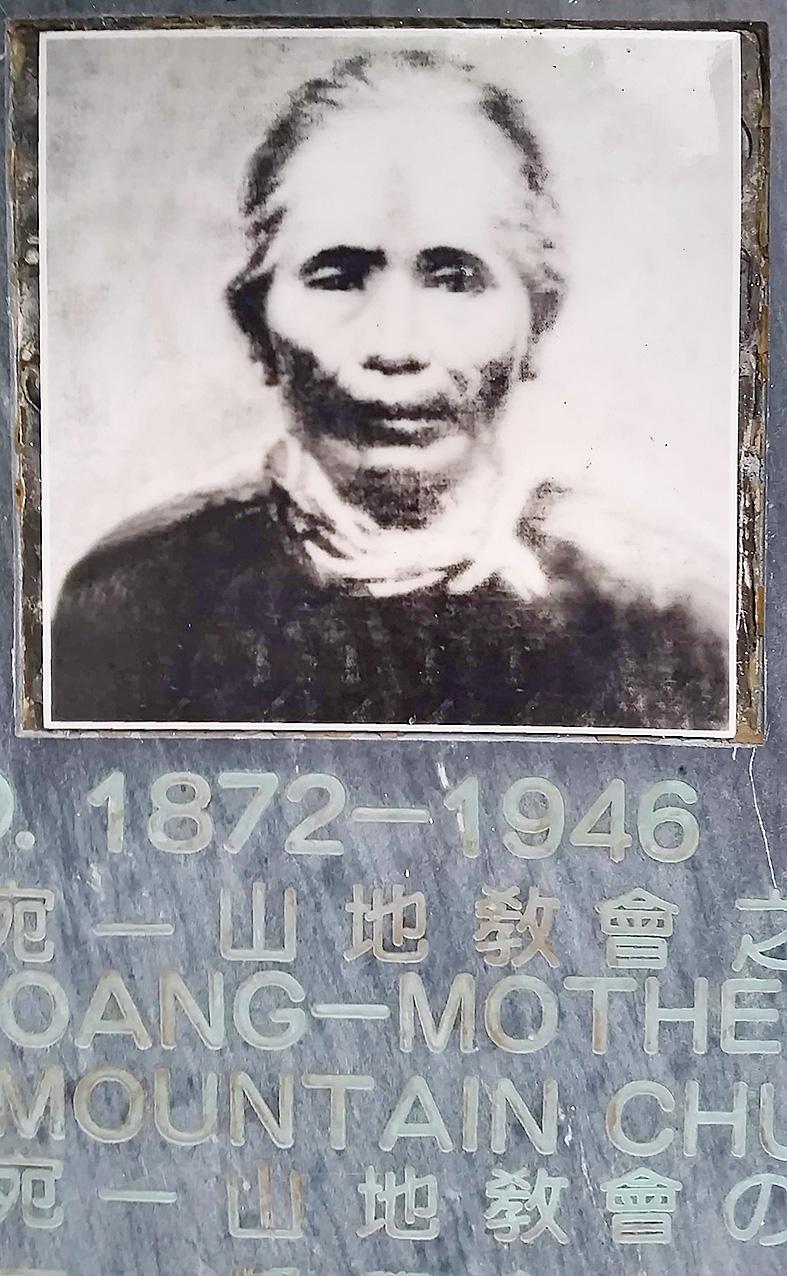

Ciwang died the following year, and is still revered today as the first Truku convert to Christianity and an influential figure by the large number of Truku who still follow the religion today.

THREE HUSBANDS

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Christian missionaries first arrived in Taiwan with the Dutch in the 1600s, but they were expelled by Chinese warlord Cheng Cheng-kung (鄭成功, also known as Koxinga) and banned by the Qing until the signing of the Treaty of Tianjin in 1859. But few missionaries penetrated into the mountain areas where the Truku and other Aboriginal groups lived.

The Japanese allowed missionaries to do their work in Taiwan for the first few decades of their rule beginning in 1895, although they were forbidden from entering the mountain areas. The government started tightening restrictions in the early 1930s, then strictly banned the religion and punished believers later in the decade due to the kominka assimilation movement when all Taiwanese were forced to take up shintoism.

Ciwang was born in 1872 in Hualien County. When she realized that Truku who married Han Taiwanese enjoyed a better standard of living, she spurned the advances of young men in her village.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

One account states that her first two husbands were Aboriginal Kavalan traders, but others maintain that they were Han Taiwanese. But all versions say that her first husband was killed by Truku men, either out of jealousy for their wealth, or due to a misunderstanding. The second husband died of illness, while the third was a Han Taiwanese surnamed Lin (林).

While neighboring Aboriginal communities eventually submitted to the Japanese, the Truku continued to resist. Ciwang was recruited to persuade her people to lay down their arms, the exact timeline of which also varies: Truku historian and pastor Iyuq Ciyang writes that it was when the Japanese first attempted to pacify the area in 1905, while Chiu Yun-fang (邱韻芳) writes in the book Ancestral Spirits and God (祖靈與上帝) that it was around the time of the Truku War of 1914.

“My Truku brethren! I am Ciwang Iwal, please stop fighting with the Japanese, as their numbers are as plentiful as ants,” she reportedly said to each village. “We will be destroyed, surrender your guns and think about your descendants!”

Again, the accounts here vary, but she spent four years in this role and it’s said that her pleas saved a portion of her people from complete destruction. Ciwang was rewarded with land and houses, but her third husband, who secretly had another wife, spent all her money on women, gambling and opium and eventually ran off with all of her belongings.

SPREADING THE FAITH

A despondent Ciwang was about to commit suicide when Lee Shui-che (李水車) of the Hualien Port Church (花蓮港教會) and his wife reached out to her and gave her comfort and encouragement. Ciwang was baptized at the church in June 1924.

Ciwang made little attempt to convert her people for the first five years. But her fate changed when she met Canadian missionary James Dickson, who was frustrated that he couldn’t enter the mountains to convert the Truku. When he heard that there was an Aboriginal woman attending church in Hualien, he urged her to attend Bible college at Tamsui Girls’ College so she could help spread the faith.

Ciwang was reluctant because she was already 58 years old, couldn’t read and had facial tattoos. But at the encouragement of Dickson, she set out anyway. Eight months later, she returned home and started converting her people one by one.

Chiu writes that today’s Truku community has polarizing opinions of Ciwang’s legacy. Some say that she saved her people from annihilation and led them toward the “light,” while others say that she took advantage of her people with her Han-Taiwanese husbands, sided with the colonizers during the war and destroyed their traditional beliefs by introducing Christianity.

Chiu writes that the Truku are quite unique among Taiwan’s Aborigines in that they became Christianized mostly through their own people, and not foreign missionaries. She postulates that after the Japanese suppressed them in the Truku War of 1914 and banned ritualistic headhunting, the Truku lost a significant portion of their confidence and spirituality. Not only did their loss indicate that utux, the embodiment of their ancestral spirits, was no longer on their side, they also couldn’t practice headhunting to bolster their spiritual power.

“The Truku could only look outward to find another utux, and Christianity happened to be a viable possibility,” Chiu writes.

Also, brutal Japanese persecution of Truku Christians during the late 1930s and early 1940s only strengthened their faith. Christians were also persecuted in the Bible, and the Truku saw it as a symbol of valor and resistance against the colonizers. Furthermore, the Japanese often opposed Christianity on the grounds that it was an American religion, which suggested that the Japanese were in fact afraid of the Americans and Christianity.

“The fact that the Americans defeated the Japanese was further proof that the god they chose was correct and dependable,” Chiu writes.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Many people noticed the flood of pro-China propaganda across a number of venues in recent weeks that looks like a coordinated assault on US Taiwan policy. It does look like an effort intended to influence the US before the meeting between US President Donald Trump and Chinese dictator Xi Jinping (習近平) over the weekend. Jennifer Kavanagh’s piece in the New York Times in September appears to be the opening strike of the current campaign. She followed up last week in the Lowy Interpreter, blaming the US for causing the PRC to escalate in the Philippines and Taiwan, saying that as

Taiwan can often feel woefully behind on global trends, from fashion to food, and influences can sometimes feel like the last on the metaphorical bandwagon. In the West, suddenly every burger is being smashed and honey has become “hot” and we’re all drinking orange wine. But it took a good while for a smash burger in Taipei to come across my radar. For the uninitiated, a smash burger is, well, a normal burger patty but smashed flat. Originally, I didn’t understand. Surely the best part of a burger is the thick patty with all the juiciness of the beef, the

This year’s Miss Universe in Thailand has been marred by ugly drama, with allegations of an insult to a beauty queen’s intellect, a walkout by pageant contestants and a tearful tantrum by the host. More than 120 women from across the world have gathered in Thailand, vying to be crowned Miss Universe in a contest considered one of the “big four” of global beauty pageants. But the runup has been dominated by the off-stage antics of the coiffed contestants and their Thai hosts, escalating into a feminist firestorm drawing the attention of Mexico’s president. On Tuesday, Mexican delegate Fatima Bosch staged a

The ultimate goal of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is the total and overwhelming domination of everything within the sphere of what it considers China and deems as theirs. All decision-making by the CCP must be understood through that lens. Any decision made is to entrench — or ideally expand that power. They are fiercely hostile to anything that weakens or compromises their control of “China.” By design, they will stop at nothing to ensure that there is no distinction between the CCP and the Chinese nation, people, culture, civilization, religion, economy, property, military or government — they are all subsidiary