For those who don’t speak Hoklo (better known as Taiwanese), the local forms of glove puppetry and traditional opera are as inaccessible as they are colorful.

Budaixi (布袋戲, “cloth bag drama”) emerged in Fujian Province around 300 years ago, and was carried to Taiwan by Han migrants. Puppet troupes used to earn money by performing at weddings, funerals and temple celebrations, but in the early 1970s, budaixi made the transition to TV. Yunlin-based Pili International Multimedia continues to mass produce episodes that are broadcast on TV, streamed over the Internet and sold in the form of DVDs.

Taiwanese opera, like Beijing opera, is a performing art in which much of the movement is symbolic, rather than realistic. Those watching need to know that striding purposefully in circles means the character is undertaking a long journey; that wringing one’s hands is an expression of anxiety and that bravery is shown by clasping one’s hands behind one’s back. Rather than reproduce the sound of staff clashing against sword, on-stage combat takes the form of acrobatics accompanied by drums and gongs.

Photo: Steven Crook

Museums dedicated to budaixi and Taiwanese opera exist in Yilan City and Chaozhou Township (潮州) in Pingtung County. Both places can claim to be opera heartlands and puppetry strongholds. At both museums, admission is free.

TAIWAN THEATER MUSEUM

Sharing a building with the Cultural Affairs Bureau of Yilan County Government, Taiwan Theater Museum (臺灣戲劇館) has exhibition galleries on three floors coupled with a substantial amount of information in Chinese and English.

Photo: Steven Crook

Yilan is recognized as the birthplace of Taiwanese opera, which has been described as the country’s only indigenous performing art. Retired opera superstar Yang Li-hua (楊麗花) was born in Yuanshan (員山), the town next to Yilan City. The northeastern county also has rich traditions of string puppetry and glove puppetry.

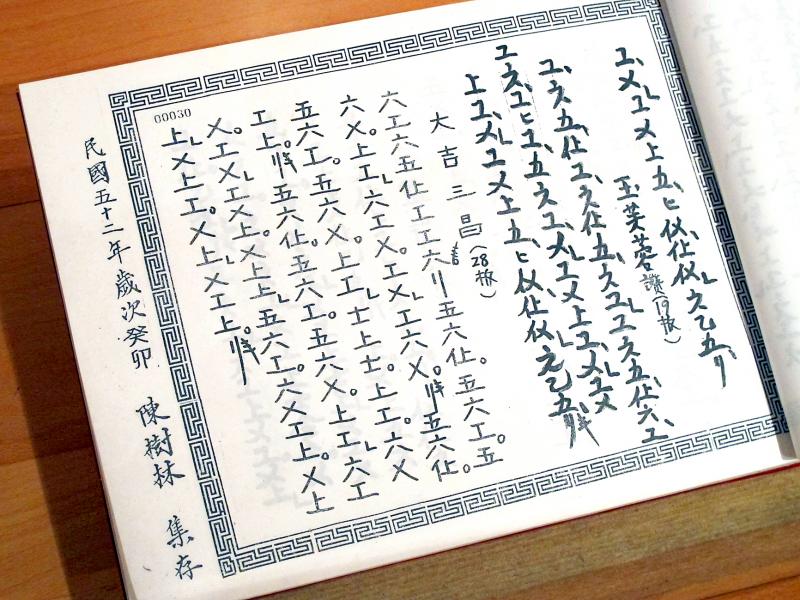

Among the items displayed on the first floor is a book of traditional sheet music, written in a format utterly different to the scores used by today’s trained musicians.

There’s also an explanation of the differences between the beiguan and nanguan forms of opera. Beiguan mostly uses a pentatonic scale, and scores are considered mere outlines which individual musicians elaborate according to their skills and preferences. Nanguan is older, preserving elements from the Tang Dynasty (618 to 907AD). The two traditions use different combinations of musical instruments.

Photo: Chiu Chih-jou

For opera costumes and props, go to the third floor. On weekends, this space is sometimes used by amateur troupes for dress rehearsals. Outsiders are welcome to watch.

The second floor has a beguiling collection of more than 100 string and glove puppets. Some were created for dramas that retell Chinese myths. Others, such as those wearing Taiwanese military uniforms, starred in anti-communist propaganda puppet shows in the 1950s.

Another display on the same floor explains how glove puppets are made. The head is wood, but the face is shaped using resin or clay. The hands, arms, shoulders, and feet are also wood, but glove puppets lack torsos. After clothes have been tailored, the face is painted. If needed, whiskers are glued on. Almost every puppet is given something to hold, such as a sword or a wand.

Photo: Steven Crook

Another location in Yilan often hosting Taiwanese opera performances is the National Center for Traditional Arts (www.ncfta.gov.tw) in Wuchieh (五結) Township.

Directions & Opening Hours

Taiwan Theater Museum is at 101 Fusing Road Sec 2 (復興路二段101號). Walking here from the train or bus stations takes 20 to 25 minutes. The museum is open 9am to midday and 1pm to 5pm from Wednesday to Sunday.

Photo: Steven Crook

MUSEUM OF TRADITIONAL THEATER

Even if you have no interest in performing arts, when passing through Chaojhou you should take a look at the charming redbrick-and-concrete building that houses the Museum of Traditional Theater (屏東戲曲故事館), also known as the Taiwanese Opera & Puppet Museum in Pingtung County.

Built in 1916 by the Japanese colonial authorities, it served as a government bureau and then a telecommunications office. For several years until Typhoon Morakot ravaged southern Taiwan in 2009, it was a post office.

Photo: Steven Crook

While tidying up after the disaster, the beams holding up the tiled roof were found to be riddled with woodworm. A full renovation was ordered, and it was decided to turn the building into a museum celebrating opera and puppetry. It has two smallish galleries, so not much time is needed to see everything inside.

Chaojhou’s connection to the world of Taiwanese opera is through Ming Hwa Yuan Taiwanese Opera Company (明華園), the country’s leading performance group. Founded by a Pingtung native in 1929, the troupe based itself in the town between the early 1960s and its rise to national fame in the 1980s.

Rather than display memorabilia, the museum uses puppets to profile the five character categories in Taiwanese opera (Beijing opera, by contrast, has four). Unfortunately, there’s no English alongside any of the Chinese texts, and the photocopied English-language introduction I was given on arrival wasn’t especially useful.

Photo: Steven Crook

The museum has fewer budaixi puppets than its counterpart in Yilan, but it’s a selection to be savored. I was especially intrigued by a gender-bending brute. Bearded, yet with feminine hands, he didn’t look happy — but neither would I, if my head was on upside-down like his.

Other eye-catching puppets include: a female convict in a cangue; a Western-looking gentleman, said to have been inspired by the Spanish priest who established a church in the nearby town of Wanjin (萬金); and various devils and deities. I now totally understand why some people collect these works of art.

Directions & Opening Hours

The museum, which is open from 9am to 5pm from Tuesday to Sunday, is 1km east of Chaojhou Railway Station at 58 Jianji Road (建基路58號). Parking nearby isn’t difficult.

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand