John Thomson was a pioneering photographer in the 19th century and one of the first to journey to East Asia. In 1871, while in China he met Dr James Laidlaw Maxwell, a fellow Scotsman who was returning to Taiwan, where he served as a Presbyterian missionary. Maxwell’s description of Taiwan intrigued Thomson, and the photographer decided to accompany Maxwell to the island then known to Westerners as Formosa.

Disembarking at Takow (today’s Kaohsiung) on April 2, 1871, Thomson brought with him the best photography equipment of his time, along with thousands of glass plates — an estimated 200kg of equipment.

The Scotsman only stayed in Taiwan for 16 days, and didn’t travel beyond the southwest, yet the images he captured and the notes he took are valuable historical materials for the research into the Taiwan of that era.

Photo: Katy Hui-wen Hung

“Exploring John Thomson’s footprints in Formosa is a fantastic way to revisit the region’s rich history, geology and ecology. By developing this ‘John Thomson Heritage Walk’ (走讀湯姆生), we hope to raise the local community’s awareness of their ancestral heritage, as well as revitalize cultural assets,” says You Yung-fu (游永福), author of the recently-published John Thomson Formosa (尋找湯姆生:1871臺灣文化遺產大發現)

You is a cultural worker who owns a small bookstore called Pumen (普門) in Jiasian Township (甲仙), which is in the hilly interior of Kaohsiung City where he was born and grew up.

The book was a labor of love, the result of dedicated research spread over the 18 years since You first heard about Thomson’s visit to Taiwan. You came across Thomson’s photographs while collecting historical materials relating to Pingpu (lowland indigenous) peoples for another project.

Photo: Katy Hui-wen Hung

In his foreword to John Thomson Formosa, historian Douglas Fix says that, from You’s “exhaustive depictions and rich illustrations, we not only know the locations where Thomson got his images, but we also have a chance to explore South Taiwan’s plains aborigines’ lifestyles and traditions in the 1870s.”

HERITAGE WALK

You held book launch events earlier this year, and he organized some related events along with the Jiasian People’s Association (甲仙愛鄉協會). Only since May, however, have fears of COVID-19 receded sufficiently for him to promote the “John Thomson Heritage Walk,” sponsored in part by Kaohsiung City Government’s Bureau of Cultural Affairs.

Photo: Katy Hui-wen Hung

You and the association jointly conducted trial walks with the support of grassroots bodies including Kaohsiung First Community University Ecological Society (高雄第一社大生態社) and Laonong Community Development Association (荖濃社區發展協會).

Feedback from participants has been positive, yet You says there’s a lot to learn and take into account before inviting the general public.

“Safety is our primary concern. Intense heat and afternoon thunderstorms pose a threat at this time of year. The ‘Laonong (荖濃) Walk’ is the first and only tour we feel confident about offering at this stage,” You says, explaining that it’s the easiest and safest route.

Photo: Katy Hui-wen Hung

You stresses the importance of bringing in the younger generation, and applying their energy and original observations to explore the various layers of culture and heritage.

On July 4, BEST — a students’ group at National Cheng Kung University (成功大學) in Tainan — completed a 10-day Thomson-themed journey from Cijin District (旗津) to Liouguei Township (六龜) in Kaohsiung.

My day-long tour with the group on June 27 was divided into three parts: Visiting the Tevorang shrine and lunch; a riverbed walk and the home where a family surnamed Huang (黃) hosted Thomson.

Photo: Katy Hui-wen Hung

THE TEVORANG PEOPLE

According to Dutch records, the Tevorang people were an indigenous ethnic group that originally settled around today’s Yujing District (玉井) in Tainan, then moved further inland due to Han Chinese encroachment.

The Laonong branch of the tribe was called Vogavon by the Dutch, and Bongabong (芒仔芒) by Han pioneers. At the Tevorang shrine we were guided by Wei Teng-ya (韋騰雅) who came from a nearby hot springs village of the Vogavon branch. Upon arrival, we paid our respects to the spirits known in Tevorang as Anag, and is commonly translated as “the Indigenous Grandmothers.”

Photo: Katy Hui-wen Hung

We were handed some betel nuts to place beside the other two essential offerings: cigarettes and rice wine. The centerpiece of the shrine — similar in size to the Earth God shrines that exist throughout Taiwan’s lowlands — is an urn. It contains xiangshui (向水, water blessed by the highest ancestral spirits), and this is where the Tevorang ancestors reside.

Xiang (向) is the most important religious concept in Tevorang animism; it conveys the idea of fear and supernatural power.

Asked if the offering of cigarettes and rice wine suggest that the Tevorang spirits aren’t necessarily female, as often stated, Wei replies: “Scholars claim that the Tevorang spirits are seven sisters, but Laonong historians and elders are doubtful, because when the Tevorang spirits appear in their dreams, it’s as a tall man, wearing only a skirt made of leaves, barefoot and carrying a gun. The shrine is also a gathering place for hunters. Even though it was a matriarchal society, it was frequented by both men and women exercising different roles.”

Photo: Katy Hui-wen Hung

Wei’s explanation of the stone sculpture behind the urn is especially interesting. The stone was a fairly recent addition, and a sign of Taoist influence.

“Some locals feel they need a physical icon to worship,” she says.

It’s said that the water inside the urn, collected from mountain springs, never stagnates. In the old days, the urn wasn’t covered; the red cloth is another Han influence, Wei says. She goes on to say that cultural workers would like to present the traditional in its original form, but some people within the local community are resisting the suggestion that the cloth be removed.

Photo: Katy Hui-wen Hung

The two wooden crows on the shrine’s roof are believed to predict happiness and misfortune. Other features includes kumato (a bamboo stand on which raw meat is hung during ceremonies), khoikhoia (bamboo clankers for scaring off birds) and wooden models of guns.

Before we moved on, Wei showed us two beautifully embroidered belts, each bearing religious symbols. Embroidery is an important handicraft among Tevorang people, with patterns and colors distinct from other indigenous groups in the region.

FEASTING ON LOCAL INGREDIENTS

Lunch was a feast of local ingredients and deliciously cooked dishes laid on banana leaves, served in neatly cut and carefully arranged bamboo boats.

We had mulberry leaf tempura; green papaya salad; steamed pork wrapped in shell ginger leaf; long-bean congee; chicken soup with ashitaba, jujube and goji berries; snails cooked three-cup style and two dishes made with Cordia dichotoma, a preserved berry that serves a similar function in Chinese cooking as does the caper in western cuisine. One was stir-fried with bitter melon, while the other was with egg. Cordia drupes have been an important food in south Taiwan for at least six hundred years.

Approaching the Laonong River (荖濃溪), we passed near a spot where, to quote You’s book, Thomson “encountered a seven-foot yellow-spotted snake. After a good fight, Thomson ended its life with a thick bamboo stick and the help of a couple of natives. The meat was left to local Pingpu people to enjoy as a delicacy.”

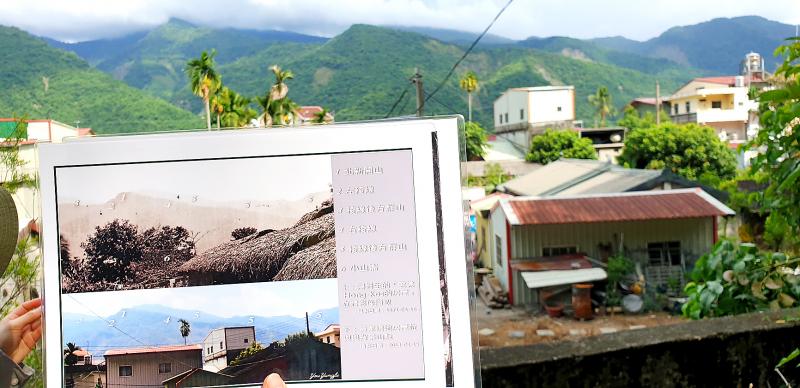

Because the intense heat ruled out walking long distances, a truck brought our party closer to where Thomson captured his images, Lau-long riverbed in dry season and The two fishermen.

Walking the final stretch, You pointed out several plants and explained their uses. Bidens alba can be used to make herbal tea; snowberry gets its Chinese name from its rice-like fruit and paper mulberry’s bark is used by Amis people to makes clothes.

On many parts of the road, we saw Java apple trees covered in black shading nets to manage sprouting and flowering, and mangoes ripening inside paper bags.

When we reached the riverbed, You pointed out the spot where Thomson took photos of two fishermen. Thomson was warned to go no further, You says, because headhunters were active on the other side. According to his research, the headhunters were likely members of the Rukai community.

HANGING OUT WITH THE HUANGS

On the evening of April 15, Thomson and his party were hosted by the Huang family (which he romanized as Hong). They “slaughtered a pig to show their hospitality; the feast included a variety of meats, rice and fresh trout,” You writes in John Thomson Formosa.

For Huang’s house, our guide was Huang Chao-ying (黃照霙), a fifth generation descendant of the couple who’d hosted Thomson. Her husband, she later revealed, had spent the weekend collecting bamboo and making the food boats for our lunch. When Huang Chao-ying first learned about her ancestors’ connection with Thomson, she was so taken aback and delighted the family slaughtered a pig.

Led by Huang Chun-ping (黃俊萍), a fourth generation descendant, we first paid our respects at the family’s Beijidian (北極殿, Heavenly North Temple), which honors the Taoist deity Xuantian Shangdi (玄天上帝). Huang Chun-ping told us that their household shifted from traditional animism to Taoism no more than 30 years ago, the decision being made by his generation.

Waiting on the other side was Liu Pan Feng-ying (劉潘鳳英), ready to demonstrate to us the ritual use of what in Tevorang is called taraw, a type of mochi made with sorghum. It’s both a local specialty and a traditional offering during “The Night Ceremony” (夜祭), the most important day for all Tevorang people to worship the Kuba ancestors.

Liu Pan is one of the few Pingpu elders in the village still able to speak “banana colloquial dialect” (香蕉白話), a form of speech developed during the Japanese colonial period in which speakers input certain vowels and consonants into their mother tongues, so eavesdropping Japanese wouldn’t understand what was being said.

After I got back to Taipei, Wei Teng-ya explained to me that the adding of syllables can be quite arbitrary. She shared a few examples of the dialect. In conventional Taiwanese, for instance, “I didn’t buy anything” is expressed in five syllables — but speakers of “banana dialect” might use eight or 10.

For details of Thomson-themed walks, contact Jiasian People’s Association at www.facebook.com/jiaxian2006; tel: (07) 765-4099. Or contact Hun Tseng (曾麗雲) at (07) 675-4099 or hun2639@gmail.com. The tour is in Mandarin and Hoklo (also known as Taiwanese).

EDITOR’S NOTE: Steven Crook will return with his Highways and Byways column next week. Also, an earlier version stated that the price was NT$1,000; the cost for the tours has yet to be determined.

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

For many centuries from the medieval to the early modern era, the island port of Hirado on the northwestern tip of Kyushu in Japan was the epicenter of piracy in East Asia. From bases in Hirado the notorious wokou (倭寇) terrorized Korea and China. They raided coastal towns, carrying off people into slavery and looting everything from grain to porcelain to bells in Buddhist temples. Kyushu itself operated a thriving trade with China in sulfur, a necessary ingredient of the gunpowder that powered militaries from Europe to Japan. Over time Hirado developed into a full service stop for pirates. Booty could

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades