June 29 to July 5

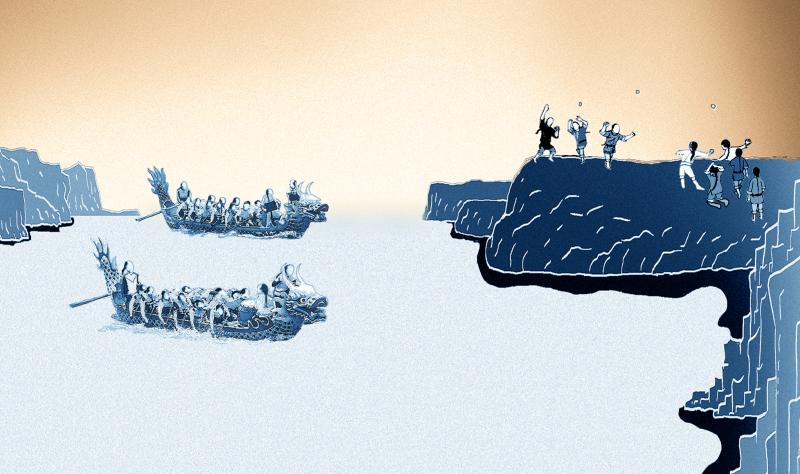

With women gathering rocks and men hurling them at thousands of rivaling neighbors, ritualistic stone battles were regular affairs for people living in Pingtung during the 1800s. Direct combat and use of weapons were prohibited to avoid serious injury, with the losers hosting the winners for dinner. These “guests” often acted rudely, and faced no repercussions for smashing windows or snatching their hosts’ possessions.

These battles usually took place yearly, with a significant number happening every Dragon Boat Festival. The winners had rights to the losers’ banquet prepared for the festivities.

Illustration: Yi-chun Chen

Sometimes things would get out of hand. One intense battle in the early 1900s resulted in the destruction of a house, which ignited a deadly gunfight. The villages decided to abolish the practice afterward, and soon, the Japanese colonizers stamped it out.

Early Han Chinese settlers in Taiwan were constantly at odds with each other, divided by place or origin in China or by clan. Disputes often ended in armed conflict, and scheduled rock fighting developed as a ritual to settle scores with less bloodshed. This phenomenon was common in Pingtung, Yunlin, Changhua and Taichung, writes Tai Pao-tsun (戴寶村) in an Historical Monthly (歷史月刊) article.

The people of Bengang (笨港) in today’s Chiayi County were among those who scheduled their bouts for Dragon Boat Festival. The Hsu clan (許) battled the joint forces of the Tsai (蔡) and Yang (楊) clans. The Hsus and Yangs were rivals in the peanut and sesame oil industry, but the Yangs had the support of the powerful Tsais, who controlled the port. The Chen (陳) clan also wielded considerable local influence, but stayed neutral.

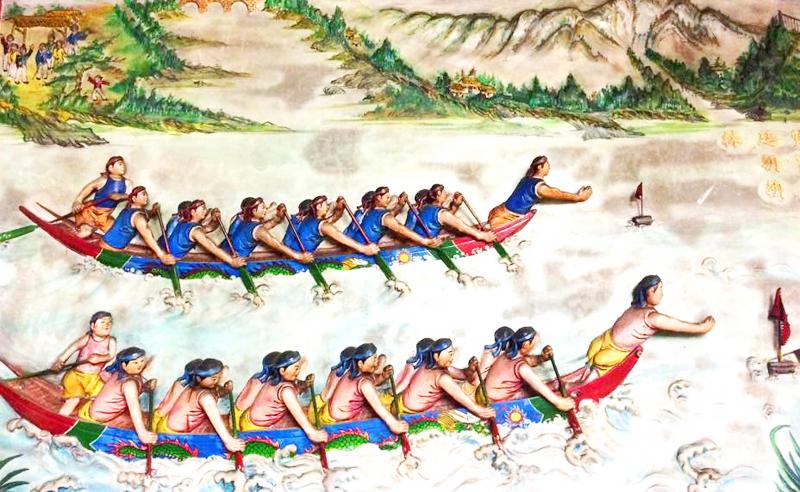

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

One year, despite a malaria epidemic, infected villagers in Pingtung still braved the battlefield for their annual clash. Legend has it that their symptoms subsided after heavy sweating, and they attributed their miraculous recovery to the battle. Later on, people began believing that participation in the fight would give them a peaceful and healthy year; some even believed that if they did not have a rock fight, disaster would befall the entire area.

Since armed warfare still broke out between villages, the stone fights were also a way to keep the villagers ready for battle.

“The participants were like an army brigade. They trained all year under a commander, and as soon as it was Dragon Boat Festival, the entire village mobilized quickly,” writes Seiichiro Suzuki in the book Taiwan’s Past Customs and Beliefs.

Those who were captured fleeing the battlefield were punished by being stripped of their pants, and the injured would shamefully leave town to treat their wounds.

The Japanese saw stone fighting as one of the “bad habits” that they had to rid the Taiwanese of when they arrived in 1895. A 1909 report shows a police force dispersing a bout after it raged on for days.

“To completely uproot these vulgar practices, we must hold more youth sports competitions during Dragon Boat Festival,” writes Suzuki. It was already 1934, and he writes that while the rock fights have been mostly curbed, small-scale ones still occasionally break out.

LORD OF WATERS

The ancient Chinese poet and bureaucrat Qu Yuan (屈原) allegedly drowned himself in despair over the emperor’s disastrous policies. To prevent his body from being devoured by fish, saddened locals threw glutinous rice dumplings called zongzi (粽子) into the river. To honor his memory, the people would eat zongzi on the anniversary of his death, and dragon boat races developed from them sailing up and down the river trying to find his body.

But some experts say that the people of southeast China had been holding dragon boat races around the same time long before Qu’s death to ward off evil and mark the beginning of summer.

Nevertheless, Qu is worshipped in Taiwan among the Taoist pantheon’s water gods. There is only one temple with him as the main deity in the nation: Zhoumei Quyuan Temple (洲美屈原宮) in Beitou, and it’s the only water god temple that still holds dragon boat races.

Temple annals state that the effigy of Qu Yuan was brought to Taiwan in 1721 by a Chinese sailor answering the rebel Chu Yi-kuei’s (朱一貴) calls for reinforcements. It’s not clear whether he brought Qu Yuan as the patron deity of his village, or for good luck on the perilous journey across the Taiwan Strait.

Chu’s uprising failed, and the effigy ended up in the Zhoumei community. The villagers cast divination blocks during a yearly ceremony to decide who would house it, and it went from house to house for the next two centuries until the community built it a permanent home in 1980.

Locals claim that Zhoumei’ dragon boat race is the oldest in Taipei. At the very least, historical records show that it was going on before 1884. During the Japanese era, the village was divided into northern and southern halves to compete against each other.

Dragon Boat Festival remains a big deal in Zhoumei and the temple and community hosts one of the larger celebrations.

Taipei Mayor Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) personally dotted the eyes of the dragon boat earlier this month to kick off the festivities, continuing centuries of tradition — minus the rock fights.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Many people noticed the flood of pro-China propaganda across a number of venues in recent weeks that looks like a coordinated assault on US Taiwan policy. It does look like an effort intended to influence the US before the meeting between US President Donald Trump and Chinese dictator Xi Jinping (習近平) over the weekend. Jennifer Kavanagh’s piece in the New York Times in September appears to be the opening strike of the current campaign. She followed up last week in the Lowy Interpreter, blaming the US for causing the PRC to escalate in the Philippines and Taiwan, saying that as

US President Donald Trump may have hoped for an impromptu talk with his old friend Kim Jong-un during a recent trip to Asia, but analysts say the increasingly emboldened North Korean despot had few good reasons to join the photo-op. Trump sent repeated overtures to Kim during his barnstorming tour of Asia, saying he was “100 percent” open to a meeting and even bucking decades of US policy by conceding that North Korea was “sort of a nuclear power.” But Pyongyang kept mum on the invitation, instead firing off missiles and sending its foreign minister to Russia and Belarus, with whom it

When Taiwan was battered by storms this summer, the only crumb of comfort I could take was knowing that some advice I’d drafted several weeks earlier had been correct. Regarding the Southern Cross-Island Highway (南橫公路), a spectacular high-elevation route connecting Taiwan’s southwest with the country’s southeast, I’d written: “The precarious existence of this road cannot be overstated; those hoping to drive or ride all the way across should have a backup plan.” As this article was going to press, the middle section of the highway, between Meishankou (梅山口) in Kaohsiung and Siangyang (向陽) in Taitung County, was still closed to outsiders

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has a dystopian, radical and dangerous conception of itself. Few are aware of this very fundamental difference between how they view power and how the rest of the world does. Even those of us who have lived in China sometimes fall back into the trap of viewing it through the lens of the power relationships common throughout the rest of the world, instead of understanding the CCP as it conceives of itself. Broadly speaking, the concepts of the people, race, culture, civilization, nation, government and religion are separate, though often overlapping and intertwined. A government