April 20 to April 26

The windows of Hoping Hospital were plastered with white banners as staff members clashed with the police as they were trying to escape. One nurse even tried to jump out the eighth floor window before being stopped by colleagues.

“We are healthy people, we want separation from SARS patients. We want to get out of Hoping Hospital and we don’t want to wait for death,” one sign read.

Photo: Wang Ching-wei and Chu Pei-hsiung, Taipei Times

Several days earlier on April 24, 2003, the Taipei City Government’s newly established SARS Emergency Response Task Force ordered the hospital to lock down and for its over 1,000 staff and patients to return to the facility to undergo collective quarantine for two weeks.

The move came after seven hospital staff came down with possible SARS symptoms on April 22. Up to that point, Taiwan had only seen 28 cases since the virus was first confirmed on March 14 and proudly announced its “three zeros” just a few days earlier: zero deaths, zero cluster infections and zero exported cases.

The number of suspected cases stemming from the hospital grew to 26 by the day of the shutdown. Panic ensued, especially due to the abruptness of the decision. Unprepared to deal with the situation, conditions in the hospital quickly worsened.

Photo: Wang Ching-wei and Chu Pei-hsiung, Taipei Times

Out of the 8,096 confirmed cases in 29 countries during the outbreak, 346 of them took place in Taiwan — with 150 reportedly occuring in Hoping Hospital. Reports of the hospital death toll vary between 24 and 35.

The nation’s bout with SARS is an often-mentioned factor in Taiwan’s success in containing the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Those of us who lived through the painful experience of SARS took the lessons to heart,” write Shin Kong Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital doctors Chang Tsang-neng (張藏能) and Hou Sheng-mao (侯勝茂) in the introduction to their article, “COVID-19 and the SARS experience.”

Photo: Wang Min-wei, Taipei Times

PANIC AT THE HOSPITAL

The SARS virus was first confirmed in Taiwan on March 14, imported by a businessman returning from China. It spread slowly at first, with 23 cases of infection reported over the next month.

The first case at Hoping Hospital was a laundry worker who began feeling unwell on April 12. Despite multiple tests, she was not diagnosed with SARS and remained on duty, living at the hospital and socializing with others. She was only put in an isolation room when her condition worsened on April 18, and tested positive on April 22.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The chaos in the hospital was recorded in hospital pediatrician Lin Ping-hung’s (林秉鴻) diary, which was serialized in the Liberty Times (Taipei Times’ sister newspaper). He writes that there were few directions on how exactly to carry out the quarantine, and the hospital was pretty much “under anarchy” in the first few days.

“Besides reinforcing public perception that ‘SARS spread from Hoping Hospital’ to punish us, I don’t see how this kind of quarantine adheres to virus prevention procedures. Why didn’t we just have uninfected staff members quarantine at home? If we were going to quarantine collectively, why didn’t they properly separate us?”

On April 27, Yeh Chin-chuan (葉金川), the health minister at the time, entered the hospital and remained there to ensure proper measures, keep order and boost morale. In addition to the unrest in the hospital, four staff members failed to return. Two checked themselves in after the police threatened to arrest them, and a warrant was issued on April 30 for the remaining two.

The B8 ward, where the laundry worker was being treated, was the hardest hit. A nurse says in the documentary Hoping Hospital (和平醫院) that at one point half of the 16 nurses on duty were infected, and by the time they were allowed to leave, there were only two nurses taking care of 16 SARS patients. The first nurse and doctor in Taiwan to die from SARS both worked at that ward.

Over the next week, staff and hospital workers were gradually moved out to other quarantine locations, with the last group departing on May 8.

By May 24, the situation had abated to the point that Lee Ming-liang (李明亮), head of the SARS-prevention command center, announced that people could resume their normal lives, although he stressed that the nation must remain alert. The WHO removed Taiwan from its list of infected areas on July 5.

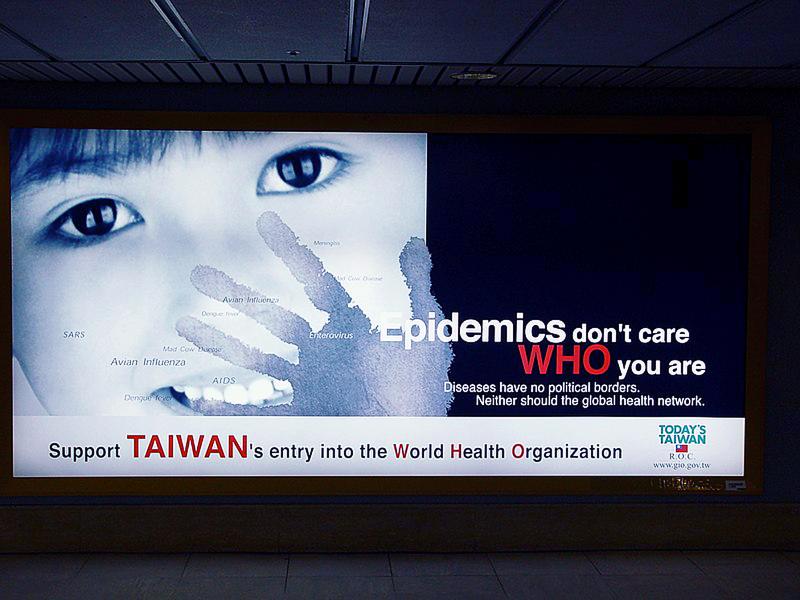

WHO CARES?

Just like the current situation, Taiwan also had its issues with the WHO back then. Researchers complained of being shut off from samples and vital information because Taiwan wasn’t a member, instead being told to go through China. Much of Taiwan’s information was received via third party, significantly bogging down the process.

According to CNN, it took the WHO seven weeks after Taiwan’s first SARS infection and after the Hoping Hospital lockdown to send experts to the nation. Taiwanese experts were also invited to attend a July SARS conference in Kuala Lumpur. To show who was in charge, however, China announced its “approval” of both decisions — although Taiwan’s government stressed that China played no role in the events.

Then-foreign minister Eugene Chien (簡又新) wrote in an op-ed for the New York Times that “[m]ember states should stop allowing political expedience to dictate WHO policy. Taiwan needs the WHO just as much as the WHO needs us in fighting SARS and future epidemics.”

On May 29, then-US president George W. Bush signed a bill pledging to support Taiwan’s bid for WHA observer status. Japan and Canada, as well as most of Taiwan’s allies, also announced their support. China was not happy.

“Taiwan, a Chinese province, does not have qualifications to join WHO under any terms,” Chinese Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Zhang Qiyue (章啟月) warned.

The bid failed. Taiwan would only get its wish in 2009 under the designation “Chinese Taipei” following the improvement of relations with China under Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) rule. The invitation was rescinded in 2017 when the KMT lost power.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,