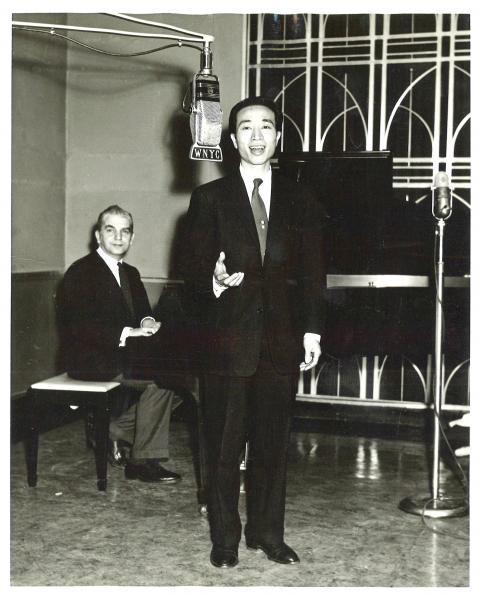

Like many Chinese immigrants in 1950s America, Stephen Cheng (程俊濤) had difficulty breaking into the entertainment industry over concerns that he was a spy.

“He graduated during the [Joseph] McCarthy era when any Chinese person was questioned about whether they were a communist,” says his son Pascal Cheng, referring to a time when many entertainers were seen as communist sympathizers.

But fortunately Stephen Cheng was working with Voice of America, which wrote a letter attesting to his character and saying he wasn’t a communist.

Photo courtesy of Chung Li Lo Photography

Evidence of Stephen Cheng’s political affiliations is scant.

“I think he was basically apolitical,” says his son. “He never wanted to talk much about the thirties and forties. It think it was pretty traumatic.”

MUSIC MAVIN

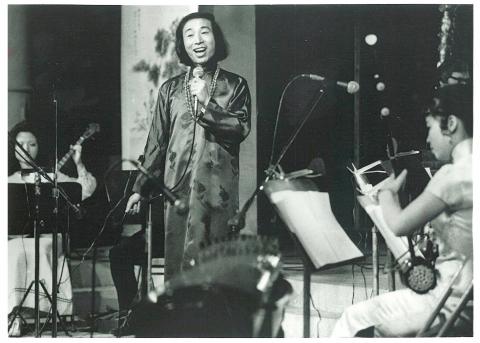

Photo courtesy of Pascal Cheng

Stephen Cheng was born to a wealthy family in Shanghai in 1923 before emigrating to the US in 1948, where he studied voice at Julliard and Columbia. Yet, there were gaps in the biography. Among his personal effects were some clues, such as an address in Shanghai’s French Concession.

“When the communists came they lost everything, including the family home. There was a big exodus of educated Chinese,” Pascal Cheng says.

Pascal Cheng says that following graduation in 1944 from St John’s University — China’s most prestigious college until it was dismantled by the communists in 1952 — his father worked as a journalist in Shanghai and southern China from 1945 to 1948. Thanks to an arrangement dating from 1905 that enabled St John’s to be registered as a domestic university in the US, graduates gained admission to American colleges.

Pascal Cheng is still unsure what spurred his father’s change of direction and how he earned a scholarship to one of the world’s most prestigious performing arts schools.

“I’m trying to learn where he got the passion for music because there isn’t anything in his background,” he said.

FITTING IN

Post-graduation, life in the US was no cakewalk.

“He didn’t do the typical Chinese immigrant thing, like open a restaurant or a laundromat,” says Pascal Cheng. “He went into the arts, which was very challenging for a Chinese immigrant. He was trying to break into entertainment and got small parts in Broadway productions like The World of Suzie Wong.”

Playing the role of hotel manager Ah Tong in the stage version of Richard Mason’s novel, Cheng trod the boards alongside William Shatner. He held his own in the production, which ran from 1958-1959, with one critic calling him the“standout” performer. It was the pinnacle of his stage career, yet he wasn’t quite able to capitalize on it.

“You need to have more than one talent to make it in the theater,” Stephen Cheng told the Jamaica Gleaner during a visit to Kingston that yielded the recording of Always Together. “It is a difficult profession, and the beginner has to be prepared to keep on and on till he makes it.”

Always Together is based on the perennial KTV favorite, the song Alishan Maiden (阿里山的姑娘), which was first recorded in 1949, shortly after the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) retreated to Taiwan.

Assumed by many to be an Aboriginal melody, the song was actually the theme to a film called Storm Clouds Over Alishan (阿里山風雲). Composition is attributed to the movie’s director, Chang Cheh (張徹), under its original title “Green is the High Mountain.” Of the many versions over the years, a 1971 cover by a 17-year-old Teresa Teng (鄧麗君) is among the most beloved. For Chinese speakers worldwide, the song is a folk standard.

Yet, Stephen Cheng’s is the most fascinating rendition, which was recorded in Kingston, Jamaica in 1967. Produced by Calypso pioneer Byron Lee, the offbeat staccato of its piano chords and plucked guitar, this unmistakably belongs to the rocksteady genre — a transitional stage in Jamaican music between ska and reggae.

But overlayed with Stephen Cheng’s plaintive warbling, it becomes something entirely different: one of the most unlikely fusions ever committed to wax. There is no way it should work, but somehow it does, and quite brilliantly.

For decades Always Together was confined to the playlists of rare groove DJs and reggae afficionados. It was so obscure that even Cheng’s family knew nothing about it.

How he ended up at Byron Lee’s studio remains unclear, but Lee was one of several Chinese-Jamaican reggae pioneers (producer Leslie Kong, whose hits included Bob Marley’s debut in 1962, and the Chin family being some of the others). It seems likely Lee met Stephen Cheng through intermediaries at the CBA.

“They did this one recording,” says Pascal Cheng. “It’s amazing because it wasn’t planned, he probably did minimal rehearsal, and just nailed the vocal.”

By the time of the Jamaica Gleaner interview — eight years after Broadway — Stephen Cheng was no longer a beginner. But he was still taking whatever came his way.

“Commercials for Kentucky Fried Chicken,” Pascal Cheng recalls. “Occasionally he did interpreting; then in the ‘60s, he did summer stock. It took a lot of persistence.”

Few avenues were unexplored. During his career, Cheng sang in at least 10 different languages and, having studied under renowned Ukrainian-American operatic bass Alexander Kipnis, his proficiency in Russian landed him a soloist role with the Don Kossack choir in 1964.

Pascal Cheng speculates that his father may have played up his Asiatic appearance to suggest connections to the Russian Far East.

‘TAO OF VOICE’

The pinnacle of Stephen Cheng’s career, in his own eyes, was the 1967 release of his LP Drum Flower Song, a collection of Chinese folk songs in a range of themes and styles — drinking ditties to ballads.

“Along with a book that he wrote called the Tao of Voice, he considered this album his greatest musical accomplishment,” says Pascal Cheng.

In the late 1960s, Stephen Cheng focused on fusing East and West in his music. The Tao of Voice had been the first step in this direction. During the 1970s, he fronted a group called the Dragon Seeds, which comprised 12 musicians on traditional Chinese instruments, supported by noted jazz musician Stan Free. They performed a UN event and, in a 1971 press release, Stephen Cheng stated the band’s aim as “unity and world peace.”

In his later years, Cheng focused on teaching aspiring performers. He passed away in 2012 aged 90.

“There was some confusion about his birth date, but we eventually found out,” says Pascal.

As for his father’s obscure legacy, Pascal Cheng is philosophical.

“On some reggae sites, he’s referred to as ‘the mysterious Stephen Cheng’ because he was there in Kingston just for a few weeks, in ‘67,” says Pascal Cheng. “People in the reggae community didn’t know him, then he disappeared, so he was just this mysterious person. ‘Where did he go?’”

It’s a good thing that 2025 is over. Yes, I fully expect we will look back on the year with nostalgia, once we have experienced this year and 2027. Traditionally at New Years much discourse is devoted to discussing what happened the previous year. Let’s have a look at what didn’t happen. Many bad things did not happen. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) did not attack Taiwan. We didn’t have a massive, destructive earthquake or drought. We didn’t have a major human pandemic. No widespread unemployment or other destructive social events. Nothing serious was done about Taiwan’s swelling birth rate catastrophe.

Words of the Year are not just interesting, they are telling. They are language and attitude barometers that measure what a country sees as important. The trending vocabulary around AI last year reveals a stark divergence in what each society notices and responds to the technological shift. For the Anglosphere it’s fatigue. For China it’s ambition. For Taiwan, it’s pragmatic vigilance. In Taiwan’s annual “representative character” vote, “recall” (罷) took the top spot with over 15,000 votes, followed closely by “scam” (詐). While “recall” speaks to the island’s partisan deadlock — a year defined by legislative recall campaigns and a public exhausted

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful