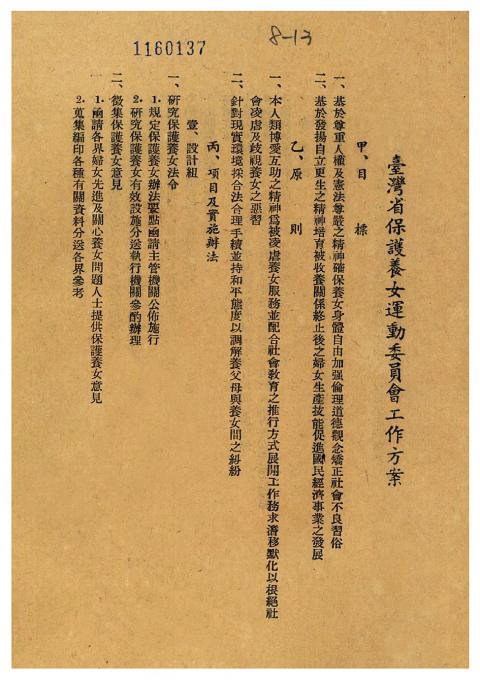

July 22 to July 28

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, it was not uncommon for lovers who could not be together to drown themselves in the Tainan Canal. While the practice was eventually curbed, the love story of one of these couples — between a married man and a prostitute — lived on through Taiwanese operas and novels, spawning at least two feature films in the 1950s.

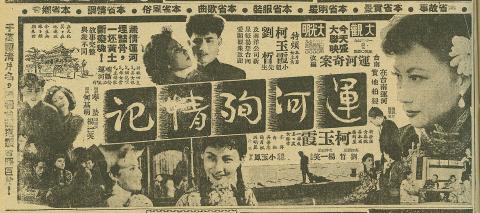

The version presented in the popular 1956 film The Canal Suicides (運河殉情記) told of the stark reality for many unfortunate women in Taiwan during those times. The protagonist, Chen Chin-kuai (陳金筷), was sold at a young age to another family as a foster daughter. The foster mother eventually sold her to a brothel, where she worked until she met a married man surnamed Wu (吳). Unable to change their circumstances, the lovers decided to end their lives in the canal.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Historica

The foster daughter system was a mainstay of Taiwanese society, dating back to the time when Han Chinese first arrived. Farming households would often sell their daughters if they had too many children, keeping the boys for labor and to pass on the family name.

“With the rise of industrialization and urbanization, the weakening of traditional morals and problems within the [foster daughter] system itself, people started committing heinous acts under the guise of fostering a daughter,” Lee Chang-kuei (李長貴) writes in A Study of the Institution and Problems of Foster Daughters in Taiwan (台灣養女制度與養女問題之研究).

“Not all foster daughters are abused. Of course there are foster parents who dote on them as their biological daughters, but unfortunately that situation is rare. Most parents treat the foster daughters as commodities and hardly see them as human beings,” Lee continues.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

It wasn’t until the 1950s that former Taiwan Provincial Assembly member Lu Chin-hua (呂錦花), a former foster daughter herself, started a movement to help these women that the problem started to abate.

FOSTER ARRANGEMENT

Government statistics show that in 1958, close to when The Canal Suicides came out, there were 189,841 foster daughters in Taiwan. Lee writes that the system made sense in an agricultural society.

Photo courtesy of Open Museum

“It took about the same resources to raise a girl, but her ‘usefulness’ was far inferior to a boy. It was a ‘losing business,’ so they might as well ‘give’ the daughter at a high price to another family. That way, they not only received immediate profit, but also avoided having to pay her dowry in the future,” Lee writes.

The richer family who bought the girl could marry her to their son, take in a son-in-law or have her help with household chores. For them, it was a small price to pay, and the arrangements made both families happy.

While there were laws to protect the foster daughters, Lee writes that they were not enforced, nor did they have any restrictions on the type of person who could adopt them except that they had to be at least older by 20 years. The poor treatment entailed physical abuse including rape, forced prostitution, forced marriages, as well as confiscating their documents, restricting their movements and denying them formal education.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The issue got to the point where “between the 1950s and 1970s, the foster daughter system was seen as a vital cog to the sex industry,” Yu Chien-hui (游千蕙) writes in The Movement to Protect Foster Daughters in 1950s Taiwan (1950年代台灣的保護養女運動). Lee writes that the general impression in those days was: “There is nothing more poisonous than a foster mother” (無毒不養母).

MOTHER OF FOSTER DAUGHTERS

Born in 1909, Lu was one of the few lucky foster daughters who grew up in a loving household. She graduated from what is today’s Taipei First Girls’ High School, married into a prominent family and moved to China with her husband, Chen Shang-wen (陳尚文), in 1932. The pair returned in 1945 and became heavily involved in politics.

According to her biography on the National Museum of Taiwan History’s “Taiwan Women” Web site, Lu already watched over many abused foster daughters before she launched the movement. Her son Chen Tu-lung (陳獨龍) recalls young girls running into their home, still bleeding from their wounds, crying to Lu for help.

Women’s rights were on the rise and their roles expanding during that time, and Lu was also known as a skilled orator who was able to convincingly rally support for her cause. Coupled with her husband’s respected position in both the business and political world, she found plenty of backing.

During a provincial assembly meeting in 1951, Lu brought up the importance of helping foster daughters, inviting three women to share their tragic experiences. The government response was sympathetic, and on July 24, the Taiwan Provincial Committee for the Movement to Protect Foster Daughters (台灣省保護養女運動委員會) was born. The committee established branches across the country, aiming to bring more public attention to the abuses, to investigate individual cases and to help them find a suitable husband or develop skills for employment outside of the sex industry.

After a failed attempt in passing a similar law in 1951, the Regulations on Improving Current Practice of Foster Daughters (臺灣省現行養女習俗改善辦法) was passed in 1956.

Operating out of a tiny office above a police station, the committee took on 967 cases in its first year of operation; by 1965 it had helped a total of 5,515 women.

On the fourth anniversary of the committee’s establishment, they held a mass wedding for 12 foster daughters whom they saved from being forced into unfavorable marriages. These mass weddings were held yearly. When the foster daughters reached the proper age to marry, Lu helped them find suitable husbands, paid for the wedding expenses and provided household goods for their new lives.

In 1966, Lu established a home for foster daughters, showing that the abuses were still taking place. However, society had taken note of the problem and newspapers started reporting more abuse cases; foster daughters also felt increasingly empowered to seek help.

By 1974, the issue had improved to the point where the committee was absorbed into the Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association (台灣省婦女會), where they continued to fight for a wider range of women’s rights issues.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Late last month Philippines Foreign Affairs Secretary Theresa Lazaro told the Philippine Senate that the nation has sufficient funds to evacuate the nearly 170,000 Filipino residents in Taiwan, 84 percent of whom are migrant workers, in the event of war. Agencies have been exploring evacuation scenarios since early this year, she said. She also observed that since the Philippines has only limited ships, the government is consulting security agencies for alternatives. Filipinos are a distant third in overall migrant worker population. Indonesia has over 248,000 workers, followed by roughly 240,000 Vietnamese. It should be noted that there are another 170,000

Hannah Liao (廖宸萱) recalls the harassment she experienced on dating apps, an experience that left her frightened and disgusted. “I’ve tried some voice-based dating apps,” the 30-year-old says. “Right away, some guys would say things like, ‘Wanna talk dirty?’ or ‘Wanna suck my d**k?’” she says. Liao’s story is not unique. Ministry of Health and Welfare statistics show a more than 50 percent rise in sexual assault cases related to online encounters over the past five years. In 2023 alone, women comprised 7,698 of the 9,413 reported victims. Faced with a dating landscape that can feel more predatory than promising, many in

“This is one of those rare bits of TikTok fitness advice with a lot of truth behind it,” says Bethan Crouse, performance nutritionist at Loughborough University. “Sometimes it’s taken a bit too literally, though! You see people chugging protein drinks as they’re scanning out of their gym.” Crouse recommends the athletes she works with consume 20-30g of protein within 30-60 minutes of finishing a resistance training session. “The act of exercising our muscles increases the breakdown of muscle proteins,” she says. “In order to restore, or hopefully improve them — and get gains such as increased muscle mass or strength —

“Far from being a rock or island … it turns out that the best metaphor to describe the human body is ‘sponge.’ We’re permeable,” write Rick Smith and Bruce Lourie in their book Slow Death By Rubber Duck: The Secret Danger of Everyday Things. While the permeability of our cells is key to being alive, it also means we absorb more potentially harmful substances than we realize. Studies have found a number of chemical residues in human breast milk, urine and water systems. Many of them are endocrine disruptors, which can interfere with the body’s natural hormones. “They can mimic, block