Few people loom larger in Taiwan’s history than Cheng Cheng-kung (鄭成功, or Koxinga), the military leader who evicted the Dutch from their colony at Tainan as part of his ultimately futile campaign to defeat the Qing Dynasty and restore the Ming Dynasty.

Koxinga died mere months after the Dutch surrender in 1662. Later that year, after a succession dispute, leadership of the mini-state Koxinga had established, the Kingdom of Tungning (東寧王國), passed to Koxinga’s son, Cheng Ching (鄭經, 1642—1681). Cheng Ching was young but experienced; before he turned 20, his father had put him in charge of Ming loyalist forces in Xiamen (廈門) and Kinmen (金門).

For much of the next 18 years, Cheng Ching focused on gaining and defending territory in China. For the day-to-day administration of the Kingdom of Tungning — which never extended beyond southwestern Taiwan — he relied on a trusted aide, Chen Yung-hua (陳永華).

Photo: Steven Crook

Chen was born in 1634 in Tongan County (同安), Fujian Province. At an early age, he showed an aptitude for scholarship. After Qing forces invaded Tongan County in 1648, his father committed suicide. Chen then threw in his lot with Koxinga, who hired him as Cheng Ching’s personal tutor.

During the political struggle that followed Koxinga’s death, Chen backed his former student. He was rewarded with rapid promotion, and initiated policies that boosted food, salt and brick production. When the Qing blockade caused cloth and other imports to become very expensive, Chen advised Cheng Ching to bribe the Qing commanders enforcing the embargo; this was done, and goods once again flowed into the island. Chen’s role in the Kingdom of Tungning has been likened to that of a modern prime minister.

Chen is said to be the inspiration behind the character Chen Jinnan (陳近南) in the martial arts novels of Louis Cha (查良鏞), the Hong Kong writer better known by his pseudonym Jin Yong (金庸). Cha wasn’t the first to apply this name to stories based on the life of Chen Yung-hua. Long before he wrote his books, there were rumors that Chen had engaged in espionage against the Qing Empire, and that from Taiwan he communicated with spies and saboteurs working for him in China under the alias Chen Jinnan.

Photo: Steven Crook

A major thoroughfare in central Tainan, Tungning’s capital city, is named for Chen Yung-hua, as is a longish road in Tainan’s Yongkang District (永康).

Recognizing the need for trained administrators, Chen set up Taiwan’s first Confucian school and, on the same site, its first Confucian temple. Fittingly, the neighborhood which includes not only Tainan Confucius Temple (台南孔廟), but other major landmarks such as the National Museum of Taiwan Literature (國立臺灣文學館), is now known as Yonghua Borough (永華里).

Less than 100m from the Confucius Temple, just off tourist-jammed Fuzhong Street (府中街), there’s a small shrine that bears Chen’s name. The official address of Yonghua Temple (永華宮) is 20, Lane 196, Fuqian Road Section 1 (府前路一段196巷20號).

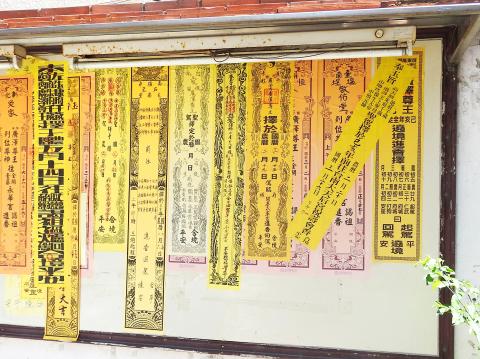

Photo: Steven Crook

The first hall of worship on this site was founded in 1662 and dedicated to King Guangze (廣澤尊王, or Guangze Zunwang). It’s said the human who was later deified as King Guangze was a shepherd who lived in 10th-century Fujian. He was filial and virtuous, but died at the age of 16.

The temple was rebuilt in 1750 after King Guangze was credited with ridding the neighborhood of troublesome ghosts. At the same time, it was renamed in honor of Chen. There’s a small statue of Chen inside, but King Guangze remains the focal point of the prayers offered and rituals conducted here.

It’s an atmospheric and photogenic shrine that faces a pair of banyan trees. Both are adorned with scores of name-card-sized wooden plaques on which visitors can write prayers or wishes. This custom reached Taiwan from Japan, where the little blocks are known as ema.

Photo: Steven Crook

Chen’s political fortunes rose and fell with those of Cheng Ching. After the collapse of his final military expedition to China, Cheng returned to Taiwan in June 1680. It seems Cheng lost the will to live, and without his patron’s protection, Chen was almost immediately sidelined by a pair of power-hungry generals.

He withdrew completely from the public arena, and moved to Chishan Longhuyan Temple (赤山龍湖巖), a Buddhist temple he had founded 15 years earlier in what is today Tainan City’s Liujia District (六甲區). (See the March 15, 2019 Highways & Byways column for more details about this place.)

Within weeks, Chen was dead. His wife passed away shortly thereafter, and the pair were buried a few kilometers north of the temple at a spot that’s now just inland of Freeway No. 3. The nearest village is Guoyi (果毅). Google Maps implies it’s possible to reach the grave via County Route 174 and Township Route 110, but even on a bicycle it isn’t.

Photo: Steven Crook

Heading first to County Route 165, to the west of Freeway No. 3, I found a Chinese-language sign which pointed me in the right direction. A minor road goes beneath Freeway No. 3, and from there it was easy to find the tomb. Even after post-World War II restoration, it’s far from Greater Tainan’s most exciting sight, but history mavens will derive a good bit of satisfaction from getting here.

An on-site bilingual information board says the grave was lost until 1929. Unfortunately, I’ve not been able to find out how it was decided that this tomb once contained the bones of Chen and his wife. The countryside, after all, is littered with old graves, many of which have been moved or emptied by descendants of the deceased, or broken open by grave robbers.

Less than a year after Chen’s death, Cheng Ching also died. The Kingdom of Tungning soon submitted to Qing rule, and the imperial authorities decided that Chen (along with Koxinga, Cheng Ching, and other heavyweight figures from the Kingdom of Tungning) be reinterred in Fujian, lest their tombs inspire anti-Qing sentiment. Presumably, their spirits didn’t object to this posthumous repatriation.

Steven Crook has been writing about travel, culture, and business in Taiwan since 1996. He is the co-author of A Culinary History of Taipei: Beyond Pork and Ponlai, and author of Taiwan: The Bradt Travel Guide, the third edition of which has just been published.

Aug. 4 to Aug. 10 When Coca-Cola finally pushed its way into Taiwan’s market in 1968, it allegedly vowed to wipe out its major domestic rival Hey Song within five years. But Hey Song, which began as a manual operation in a family cow shed in 1925, had proven its resilience, surviving numerous setbacks — including the loss of autonomy and nearly all its assets due to the Japanese colonial government’s wartime economic policy. By the 1960s, Hey Song had risen to the top of Taiwan’s beverage industry. This success was driven not only by president Chang Wen-chi’s

Last week, on the heels of the recall election that turned out so badly for Taiwan, came the news that US President Donald Trump had blocked the transit of President William Lai (賴清德) through the US on his way to Latin America. A few days later the international media reported that in June a scheduled visit by Minister of National Defense Wellington Koo (顧立雄) for high level meetings was canceled by the US after China’s President Xi Jinping (習近平) asked Trump to curb US engagement with Taiwan during a June phone call. The cancellation of Lai’s transit was a gaudy

From Godzilla’s fiery atomic breath to post-apocalyptic anime and harrowing depictions of radiation sickness, the influence of the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki runs deep in Japanese popular culture. In the 80 years since the World War II attacks, stories of destruction and mutation have been fused with fears around natural disasters and, more recently, the Fukushima crisis. Classic manga and anime series Astro Boy is called “Mighty Atom” in Japanese, while city-leveling explosions loom large in other titles such as Akira, Neon Genesis Evangelion and Attack on Titan. “Living through tremendous pain” and overcoming trauma is a recurrent theme in Japan’s

As last month dawned, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was in a good position. The recall campaigns had strong momentum, polling showed many Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers at risk of recall and even the KMT was bracing for losing seats while facing a tsunami of voter fraud investigations. Polling pointed to some of the recalls being a lock for victory. Though in most districts the majority was against recalling their lawmaker, among voters “definitely” planning to vote, there were double-digit margins in favor of recall in at least five districts, with three districts near or above 20 percent in