JUNE 24 to JUNE 30

Accusations of “Green Terror” reignited this week as the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) increased sentences and fines for people spying for China (and other countries) on Wednesday. They did so by amending the National Security Act (國家安全法), which was implemented on July 1, 1987 before the lifting of martial law on July 15.

This was the same act that served as the basis for the indictment of New Party spokesman Wang Ping-chung (王炳忠) on espionage charges in June last year, which was also decried by political opponents as “Green Terror.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

What’s intriguing about this situation is that exactly 32 years ago today, DPP members staged a sit-in at the Legislative Yuan to protest the act, calling it a device for the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) to continue its reign of “White Terror” despite its promises to end martial law. The act was implemented anyway, and after several amendments over the decades, it still exists and the tables have turned in a drastically different political landscape.

Since the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) ban on opposition parties was still in effect at that time, the DPP was technically illegal and its members ran as independent candidates; newspaper reports back then put all references to the party in quotation marks. This ban ended with the lifting of martial law less than a month later.

COMMUNISTS STILL A THREAT

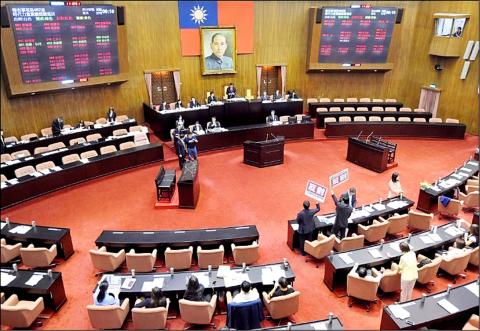

Photo: Huang Yao-cheng, Taipei Times

Upon the passing of the National Security Act on June 24, 1987, then-president Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國) stated in a speech that the law would “bring our country forward into a brand new era.”

“A secure environment is the most important condition for economic development and the road to democracy,” he continued. “In 1949, when our country was in a most perilous situation, martial law was declared to ensure our security … Now that [martial law] has served its purpose, under the protection of the new act, we will create a more democratic and free society that’s prosperous and progressive …”

Opposition groups had been protesting the act ever since the KMT announced their plans in October 1986. On the anniversary of the May 19, 1986 rally to end martial law, crowds gathered again to oppose the act. On June 12, supporters and critics of the law clashed in front of the Legislative Yuan.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The original version of the act still refers to the “Period of mobilization for the suppression of Communist rebellion” which wasn’t lifted until 1991. Article 2 prohibits people from gathering or forming groups for unconstitutional reasons, promoting communism or attempting to divide the country. Article 3 prohibits certain persons from leaving the country, including wanted criminals and those who are suspected with sufficient evidence of obstructing national and social security.

The next few lines appear to be general rules on border security and military zones. Military trials were banned for civilians, and provisions laid out for those undergoing trial or already convicted.

Article 2 has since been deleted from today’s version, replaced by an article prohibiting people from spying or working on behalf of the government, military or other public institutions belonging to foreign countries in addition to “the mainland.” Article 3 has also been deleted. The rest of it remains pretty much intact, except for adjusted punishments.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

THE ARGUMENTS

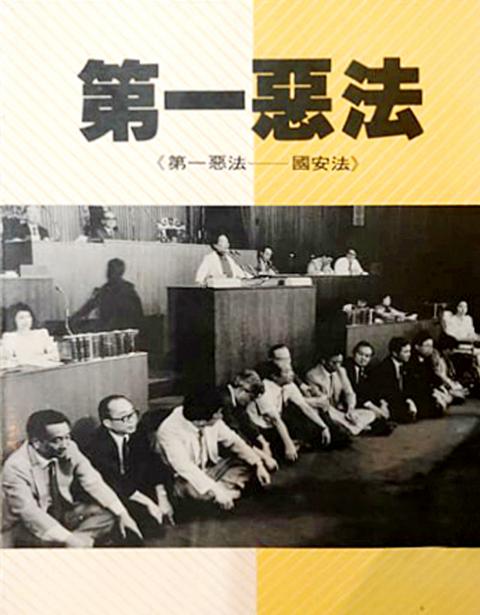

Two books provide drastically contrasting perspectives on the law, shedding light on the points of contention between the KMT and DPP. Published in November 1987, The Number One Unjust Law: National Security Act (第一惡法—國安法) is a scathing critique that blasts the act as a tool for the KMT to retain authoritarian control over Taiwan. Three months later, Rebuilding Law and Order After the Lifting of Martial Law (解嚴後的法序再建) hit the shelves, defending the act as necessary to protect Taiwan against the evil Chinese Communists and bashing the DPP as troublemakers trying to undermine national safety.

The book supporting the act states: “The lifting of martial law is conditional upon the act, because unconditional lifting of martial law means unconditional surrender [toward the communists].”

“The National Security Act will not hamper political reform, but we cannot abandon our nation’s safety in the name of political reform.” The author states that without the act, the existing laws are not enough to protect the country. “It is time consuming and unnecessary to maintain national security through a number of separate laws.”

“If anyone opposes the National Security Act, they are essentially destroying the foundation of the walls that protect our anti-communist fortress of Taiwan. Surely nobody would be so heartless to sacrifice the freedom and property of the 19 million residents of Taiwan.”

The Number One Unjust Law accuses the KMT of pushing through the National Security Act just before the newly elected legislators took office in March 1987, which would include 13 DPP members who would surely vote against it.

“After martial law is lifted, the country should return to constitutional rule,” it stated. “Replacing martial law with the National Security Act is sufficient evidence that the KMT has no sincerity in doing so…”

The DPP was very unhappy with the first draft, and the process of revising the draft dragged on as discussions intensified between the two sides, often erupting in conflict. After a tense 15th session on June 19, 1987, the DPP walked out, and the law was quickly pushed through.

The lawmakers who staged a sit-in at the Legislative Yuan on June 23 made the following statement: “The act restricts the basic freedom and the rights of the people; how is that different from martial law? The fact that the ruling party is adamant in passing the act before the lifting of martial law shows that it has no intention of returning the country to normal.”

Although many restrictions were relaxed by the lifting of martial law, this was just the beginning of Taiwan’s path toward democracy, which would take almost another decade.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Oct. 27 to Nov. 2 Over a breakfast of soymilk and fried dough costing less than NT$400, seven officials and engineers agreed on a NT$400 million plan — unaware that it would mark the beginning of Taiwan’s semiconductor empire. It was a cold February morning in 1974. Gathered at the unassuming shop were Economics minister Sun Yun-hsuan (孫運璿), director-general of Transportation and Communications Kao Yu-shu (高玉樹), Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) president Wang Chao-chen (王兆振), Telecommunications Laboratories director Kang Pao-huang (康寶煌), Executive Yuan secretary-general Fei Hua (費驊), director-general of Telecommunications Fang Hsien-chi (方賢齊) and Radio Corporation of America (RCA) Laboratories director Pan

The consensus on the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chair race is that Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) ran a populist, ideological back-to-basics campaign and soundly defeated former Taipei mayor Hau Lung-bin (郝龍斌), the candidate backed by the big institutional players. Cheng tapped into a wave of popular enthusiasm within the KMT, while the institutional players’ get-out-the-vote abilities fell flat, suggesting their power has weakened significantly. Yet, a closer look at the race paints a more complicated picture, raising questions about some analysts’ conclusions, including my own. TURNOUT Here is a surprising statistic: Turnout was 130,678, or 39.46 percent of the 331,145 eligible party

The classic warmth of a good old-fashioned izakaya beckons you in, all cozy nooks and dark wood finishes, as tables order a third round and waiters sling tapas-sized bites and assorted — sometimes unidentifiable — skewered meats. But there’s a romantic hush about this Ximending (西門町) hotspot, with cocktails savored, plating elegant and never rushed and daters and diners lit by candlelight and chandelier. Each chair is mismatched and the assorted tables appear to be the fanciest picks from a nearby flea market. A naked sewing mannequin stands in a dimly lit corner, adorned with antique mirrors and draped foliage

The election of Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) as chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) marked a triumphant return of pride in the “Chinese” in the party name. Cheng wants Taiwanese to be proud to call themselves Chinese again. The unambiguous winner was a return to the KMT ideology that formed in the early 2000s under then chairman Lien Chan (連戰) and president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) put into practice as far as he could, until ultimately thwarted by hundreds of thousands of protestors thronging the streets in what became known as the Sunflower movement in 2014. Cheng is an unambiguous Chinese ethnonationalist,