I often wonder why it took me so long to appreciate chrysanthemum greens (茼蒿). I usually blame hotpot restaurants, for no better reason than the greens often get dumped into the broth and then are allowed to go mushy. It was not a great introduction. So I resisted using these excellent greens for a long time, until I was pressed into making Hakka-style savory tangyuan (湯圓, glutinous rice balls), when I discovered that with proper control, chrysanthemum greens can be truly delicious, and are a key aspect of this Chinese festive dish.

These greens can also be used in a wide variety of other dishes, from salads to soups, infusing dishes with a splendid grassy flavor that cuts through oil and gives dishes a refreshing punch.

Chrysanthemum greens are more properly called glebionis coronaria, with common names such as garland chrysanthemum, chop suey green and crown daisy. My own preferred name is the last, and will use that here.

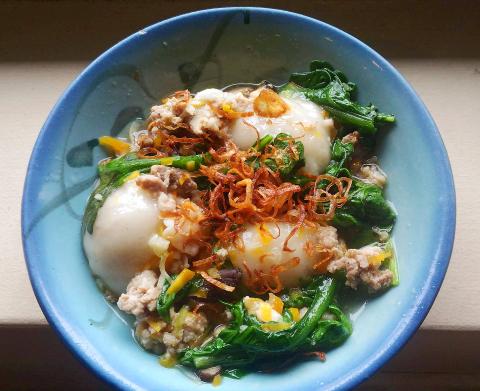

Photo: Ian Bartholomew

Crown daisies are most often found as an ornamental flower in the west but its leaves are highly prized as a vegetable in East Asia. They are cheap and hardy, have a herbaceous flavor and a very slight bitterness that is a great boon for cooks, and are packed with many substances that are excellent for those seeking to achieve better health or to lose weight.

According to the Health with Food Web site, crown daisy “is rich in chlorogenic acid (a type of hydroxycinnamic acid), carotene, flavonoids, vitamins and potassium, and can offer a multitude of health benefits. Some of the beneficial effects associated with eating garland chrysanthemum leaves include weight loss, antioxidant protection, a reduced risk of lung cancer, as well as protection against cardiovascular problems, kidney stones, cellulite, bloating and bone loss.” (www.healwithfood.org/health-benefits/garland-chrysanthemum-leaves.php#ixzz5aqqHqCuM).

These are huge claims for what, to many, is merely part of the herbaceous border, but it should be noted that it is becoming increasingly evident that many long neglected plants have outstanding health-giving qualities that are not present or have been bred out of mainstream foods. In Taiwan, crown daisy remains part of the culinary mainstream, but it sadly is not given the respect that it deserves. If hotpot restaurants are allowed to have their way with them they will soon be relegated to oblivion.

Photo: Ian Bartholomew

Using crown daisy well generally involves no more than finding a good supplier, ideally a farmer who brings his or her own produce to the traditional market and has taken care to pick young leaves. Older crown daisy leaves are still perfectly usable, but require a little more exposure to heat and other flavors to tame their bitterness, while the tartness of the young leaves is refreshing and requires little interference from the cook. In Japanese cuisine, blanched crown daisy leaves is served with a miso or sesame seed dressing, a perfect foil for richer foods.

In my own more minimalist moods, I enjoy tossing a bowl of crown daisy leaves with some stewed minced pork, letting the steamy pork mince do all the cooking that is necessary. The grassy flavor of the leaves provides a wonderful counterbalance to the richly flavored meat.

There are a number of varieties of crown daisy leaves available in the markets, including regular crown daisy, with rounder leaves, and mountain or Japanese crown daisy, with more pointed leaves. There are slight flavor and textural differences, but they can be used pretty much interchangeably. Crown daisy should be bought fresh and used as soon as possible. They will keep for two to three days in the vegetable crisper, but will go down hill pretty quickly after that.

Savory Hakka Tangyuan in Broth

Recipe

(Serves 4)

Tangyuan are associated with the lunar New Year and most specifically with the Spring Lantern Festival, but are available throughout the year. Tangyuan are a dumpling made of ground glutinous rice, often with a sweet filling of peanut, black sesame or red bean paste. Savory tangyuan, filled with a ground pork mixture, are a Hakka specialty that are served with a meat broth and can constitute a meal by themselves. At the moment, many traditional market stalls have already begun the production and sale of tangyuan, and savory tangyuan, while not as ubiquitous, are readily available both fresh and frozen. In most recipes, dried shrimp is called for, and the seafood savor that this imparts is an important part of the authentic flavor. The use of fresh shrimp is not usual, but I prefer the more delicate flavor that they infuse into the broth, but this is purely a personal preference. Deep-fried shallots, which are part of the traditional garnish, are easily available commercially, but it pays to make your own, as the flavor is incomparably better (to my mind, all the mass market brands taste of little more than rancid oil). Simply deep-fry chopped shallots in vegetable oil at about 120c for about a minute, until just turning golden and then remove to drain on kitchen paper. They store well for a week.

Ingredients

12 Hakka-style savory tangyuan

100g coarsely minced pork

4 shrimp, shelled, deveined and roughly chopped

4-5 dried Chinese mushrooms

1 clove garlic, minced

4 cloves shallots, minced

1 stem Chinese celery, finely minced

quarter carrot, finely diced

2 cups vegetable stock

1 tablespoon deep-fried shallots (油蔥酥)

1 bunch crown daisy leaves

salt and white pepper to season

2 teaspoons vegetable oil

Directions

1. Soak the dried Chinese mushrooms in boiling water. Once re-hydrated, discard the water, slice finely and set aside.

2. Season the minced pork with salt and white pepper.

3. Wash the crown daisy leaves thoroughly and cut off the base.

4. Heat the vegetable oil in a medium sized pot over low heat. Add the garlic, shallots, celery and carrot. Fry for about a minute before adding the mushrooms. Stir over heat for another minute.

5. Add the meat and continue to cook until it just begins to color, about a minute (avoid browning). Mix in the shrimp then add the stock. Simmer for 2-3 minutes.

6. Meanwhile, bring a pot of water to a boil. Add the tangyuan and cook until they float to the surface. The time will vary, but 5 minutes is about what it should take, with an addition of water midway if the pot boils too vigorously. Follow manufacturer’s instructions if provided.

7. Remove the tangyuan after they float up to the surface and transfer to the broth and allow to simmer for 1-2 minutes then toss in the crown daisy leaves. As soon as they wilt, no more than about 20 seconds, remove and divide the tangyuan and broth into bowls.

8. Sprinkle generously with deep-fried shallots and serve. Best eaten warm.

Ian Bartholomew runs Ian’s Table, a small guesthouse in Hualien. He has lived in Taiwan for many years writing about the food scene and has decided that until you look at farming, you know nothing about the food you eat.

He can be contacted at Hualien202@gmail.com.

Every now and then, it’s nice to just point somewhere on a map and head out with no plan. In Taiwan, where convenience reigns, food options are plentiful and people are generally friendly and helpful, this type of trip is that much easier to pull off. One day last November, a spur-of-the-moment day hike in the hills of Chiayi County turned into a surprisingly memorable experience that impressed on me once again how fortunate we all are to call this island home. The scenery I walked through that day — a mix of forest and farms reaching up into the clouds

With one week left until election day, the drama is high in the race for the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chair. The race is still potentially wide open between the three frontrunners. The most accurate poll is done by Apollo Survey & Research Co (艾普羅民調公司), which was conducted a week and a half ago with two-thirds of the respondents party members, who are the only ones eligible to vote. For details on the candidates, check the Oct. 4 edition of this column, “A look at the KMT chair candidates” on page 12. The popular frontrunner was 56-year-old Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文)

“How China Threatens to Force Taiwan Into a Total Blackout” screamed a Wall Street Journal (WSJ) headline last week, yet another of the endless clickbait examples of the energy threat via blockade that doesn’t exist. Since the headline is recycled, I will recycle the rebuttal: once industrial power demand collapses (there’s a blockade so trade is gone, remember?) “a handful of shops and factories could run for months on coal and renewables, as Ko Yun-ling (柯昀伶) and Chao Chia-wei (趙家緯) pointed out in a piece at Taiwan Insight earlier this year.” Sadly, the existence of these facts will not stop the

Oct. 13 to Oct. 19 When ordered to resign from her teaching position in June 1928 due to her husband’s anti-colonial activities, Lin Shih-hao (林氏好) refused to back down. The next day, she still showed up at Tainan Second Preschool, where she was warned that she would be fired if she didn’t comply. Lin continued to ignore the orders and was eventually let go without severance — even losing her pay for that month. Rather than despairing, she found a non-government job and even joined her husband Lu Ping-ting’s (盧丙丁) non-violent resistance and labor rights movements. When the government’s 1931 crackdown