April 16 to April 22

Prince Kotohito, who grew up during the Japanese Empire’s period of Westernization, was accustomed to the once-foreign practice of drinking milk. But milk wasn’t readily available in Taiwan, as dairy was largely absent from the local diet.

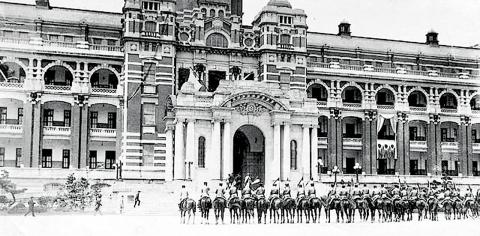

So when Kotohito was to visit Taiwan in 1908, finding milk was among the many concerns for the officials at the Governor-General’s Office (today’s Presidential Office), who were responsible for ensuring a perfect trip for the prince. They imported many of Kotohito’s preferred foods from Japan, but milk would spoil during the journey.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Carefully selecting a few cows from three Taiwanese ranches, the officials created an exclusive dairy farm, cordoned off to avoid contamination. By the 1920s, milk was readily available whenever a royal visited during the Japanese colonial era (1895-1945).

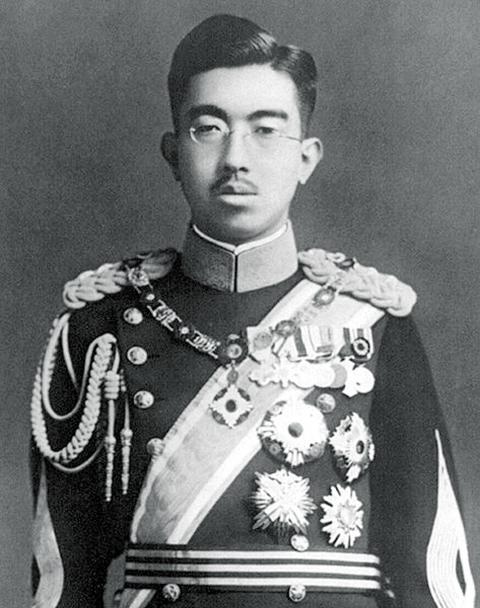

Touring various parts of Japanese territory was among the regular duties of members of the royal family, beginning in the 1870s after they reclaimed power through the Meiji Restoration. During 50 years of Japanese rule, a total of 27 royals visited Taiwan 34 times, the highest profile being future emperor Hirohito, who was crown prince when he arrived on the warship Kongo on April 16, 1923.

“In addition to performing their scheduled duties, each and every movement of the royals in Taiwan was a show, a display of authority over their subjects,” writes Chen Wei-han (陳煒翰) in his book, The Visits of Japanese Royals to Taiwan (日本皇族的台灣行旅).

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

HECTIC SCHEDULES

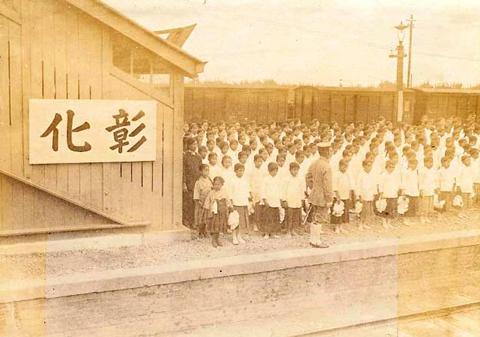

Hirohito stepped ashore in Kirun (today’s Keelung) to the loud cheers of bystanders, officials and thousands of junior high and elementary school students, who were standing in perfect formation and waving the flag of the rising sun. The prince was presented with a book with 50 photographs of Taiwanese scenery selected from more than 1,000 submissions, as well as a sculpture by noted artist Huang Tu-shui (黃土水), created for the occasion. The prince’s cargo arrived shortly after, which consisted of items ranging from soy sauce to ping pong tables as well as cars and horses.

According to Chen, 30,000 people gathered in Kirun that day for the prince to spend just five minutes before he took off in his private train. These were very expensive visits — Chen writes that Hirohito’s visit cost local authorities 60 times more than the annual salary of the highest paid Japanese official in Taiwan.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Hirohito would have a hectic 12 days in Taiwan. From the moment he arrived at his residence, he met a number of Japanese officials and Taiwanese elites, granting them honors, then heading to dinner and finally joining a lantern march in Taipei.

Chen writes that Hirohito’s whirlwind tour was not unique to royals visiting Taipei. A typical day often entailed visits to seven or eight institutions or projects, two to three cultural performances as well as meetings with prominent figures and observations of military facilities and schools. They also were brought to various scenic areas such as Nantou County’s Sun Moon Lake.

The officials even spread a legend about Hirohito: during a visit to a sugar factory, the crown prince was feeling ill due to the heat. The factory built a temporary resting place out of bamboo for the prince, but to everyone’s amazement the long-dead bamboo began to grow leaves. It was a miracle, and proved his divine status as future emperor.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

As mentioned earlier, local officials went through great pains to cater to the royals’ whims: when Prince Yasuhiko said that he wanted to visit with a commoner, a wish that was granted within 24 hours.

In addition to the official Japanese entertainment program, Taiwanese elites were allowed to put on Han Chinese performing art shows for the royals, starting with a concert organized for Princess Tomiko in 1901. These included lion dances, dragon boat races, classical nanguan (南管) and beiguan (北管) musical concerts and Taoist Song-Jiang Jhen Battle Array (宋江陣) demonstrations.

While earlier royals dined exclusively on Western and Japanese cuisine, Kotohito became the first to dine on Taiwanese food during his second visit in 1916, with a banquet catered by chef Lin Chu-kuang (林聚光), who hailed from Taipei’s Dadaocheng (大稻埕) area. Lin also cooked for Prince Naruhisa the following year.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

WAR TO PEACE TO WAR

The first royal to visit Taiwan was not as fortunate. It was 1895, and Prince Yoshihisa arrived in Taiwan to help crush local resistance against the advancing Japanese, who had obtained Taiwan by defeating the Qing Empire earlier that year. The prince either died of sickness or was killed by Taiwanese guerrillas, becoming the first member of the Japanese imperial family to perish outside of the country.

In 1901, his widow Princess Tomiko came to Taiwan to mourn her late husband. The governor-general’s office went through great pains to ensure her safety, especially since there was still local unrest and much of Taiwan had poor infrastructure. She was closely guarded at all times, and spent minimal time in public. The security included Tomiko’s meals, with many ingredients imported from Japan and closely inspected by medical staff before serving.

This practice continued throughout Hirohito’s visit, as the Japanese hosts chose to import sugar for his meals from Japan even though Taiwan was a major sugar-producing area. Chen writes that this shows how meticulous the governor-general’s office was in preparing for these visits.

By the time the next royal, Kotohito, visited in 1908 to preside over the opening of the Taiwan Trunk Line (縱貫線) railroad, the Japanese officials were confident enough in their improvements to Taiwan that the visits became less of a headache and more of an opportunity to show off their achievements.

Between 1910 and 1920, royals visited for reasons like ribbon cutting ceremonies and collecting material for educational purposes. But as Japan entered its imperialist period in the 1930s, the trips took on more of a military nature.

Chen writes that like the British royals, Japanese royals were expected to take on military duties. During wartime, several members arrived in Taiwan to conduct military inspections. While females were exempt from the military, they also had duties as Princess Masako arrived in 1938 to boost the morale of wounded soldiers in hospitals.

Career officer Prince Haruhito was the last royal to visit Taiwan in March 1941. The war would intensify soon with the bombing of Pearl Harbor later that year, and there would be no more room for such activities.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Taiwan has next to no political engagement in Myanmar, either with the ruling military junta nor the dozens of armed groups who’ve in the last five years taken over around two-thirds of the nation’s territory in a sprawling, patchwork civil war. But early last month, the leader of one relatively minor Burmese revolutionary faction, General Nerdah Bomya, who is also an alleged war criminal, made a low key visit to Taipei, where he met with a member of President William Lai’s (賴清德) staff, a retired Taiwanese military official and several academics. “I feel like Taiwan is a good example of

March 2 to March 8 Gunfire rang out along the shore of the frontline island of Lieyu (烈嶼) on a foggy afternoon on March 7, 1987. By the time it was over, about 20 unarmed Vietnamese refugees — men, women, elderly and children — were dead. They were hastily buried, followed by decades of silence. Months later, opposition politicians and journalists tried to uncover what had happened, but conflicting accounts only deepened the confusion. One version suggested that government troops had mistakenly killed their own operatives attempting to return home from Vietnam. The military maintained that the

“M yeolgong jajangmyeon (anti-communism zhajiangmian, 滅共炸醬麵), let’s all shout together — myeolgong!” a chef at a Chinese restaurant in Dongtan, located about 35km south of Seoul, South Korea, calls out before serving a bowl of Korean-style zhajiangmian —black bean noodles. Diners repeat the phrase before tucking in. This political-themed restaurant, named Myeolgong Banjeom (滅共飯館, “anti-communism restaurant”), is operated by a single person and does not take reservations; therefore long queues form regularly outside, and most customers appear sympathetic to its political theme. Photos of conservative public figures hang on the walls, alongside political slogans and poems written in Chinese characters; South

Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (蔣萬安) announced last week a city policy to get businesses to reduce working hours to seven hours per day for employees with children 12 and under at home. The city promised to subsidize 80 percent of the employees’ wage loss. Taipei can do this, since the Celestial Dragon Kingdom (天龍國), as it is sardonically known to the denizens of Taiwan’s less fortunate regions, has an outsize grip on the government budget. Like most subsidies, this will likely have little effect on Taiwan’s catastrophic birth rates, though it may be a relief to the shrinking number of