At a revolutionary school in Pakistan, Durkhanay Banuri dreams of becoming military chief, once a mission impossible for girls in a patriarchal country where the powerful army has a severe problem with gender equity.

Thirteen-year-old Durkhanay, a student at Pakistan’s first ever Girls’ Cadet College, established earlier this year in the deeply conservative northwest, brims with enthusiasm and confidence as she sketches out her life plan. “I want to be the army chief,” she says. “Why not? When a woman can be prime minister, foreign minister and governor of the State Bank, she can also be chief of the army staff ... I will make it possible and you will see.”

The dreams of many women in the region were once limited to merely leaving the house.

Photo: AFP

Durkhanay and her 70 classmates in Mardan, a town in militancy-hit Khyber Pakthunkhwa province roughly 110 kilometers from Islamabad, are aiming much higher.

MILITARY EDUCATION

Cadet colleges in Pakistan, which are run by the government with officers from the military’s education branch, strive to prepare bright male students for the armed forces and civil services.

Photo: AFP

Their graduates are usually given preference for selection to the army, which in Pakistan can mean their future is secured: they are likely to be granted land and will benefit from the best resources and training in the country.

As a result such colleges play an outsized role in Pakistan’s education system, which has been woefully underfunded for decades.

According to a 2016 government study, a staggering 24 million Pakistani children are out of school, with a larger share of girls staying home than boys — 12.8 million compared to 11.2 million.

Hundreds of boys study at the cadet colleges across the country. But girls are still not allowed in these elite schools, with the special college at Mardan the one exception.

“Such colleges can help girls qualify to be part of the armed forces, foreign service, civil services or become engineers and doctors,” said retired Brigadier Naureen Satti, underscoring their importance in the long fight for equality by Pakistan’s women.

In starched khaki uniforms and red berets Durkhanay and her classmates march the parade ground, stepping to the beat of a barking drill instructor, before racing to change into physical training and martial arts kits. The military is widely seen as Pakistan’s most powerful institution, and has ruled the country for roughly half of its 70-year history. Under the current civilian government it is believed to control defense and foreign policy. Women, however, have largely been shut out — par for the course in a country routinely ranked among the world’s most misogynistic, and where they have fought for their rights for decades.

Previously they were only allowed to serve in administrative posts. But military dictator Pervez Musharraf opened up the combat branches of the army, navy and air force to women beginning in 2003.

GAME CHANGER

The military would not disclose how many of its members, which a 2015 Credit Suisse report said number more than 700,000 active personnel, are currently women. But a senior security official who wished to remain anonymous said that at least 4,000 are now believed to be serving in the armed forces. He gave no further details, and it is unclear how far the women have managed to foray from their administrative past, though some have managed to become high profile role models — including, notably, Ayesha Farooq, who in 2013 became Pakistan’s first ever female fighter pilot. The Girls’ Cadet College principal, retired brigadier Javid Sarwar, vowed his students would be prepared for whatever they wanted to do, “including the armed forces.”

“I want these girls to avail their brilliance and fight injustices in society, and this is possible if they get a standard education,” he says, adding that plans are to induct a second batch of 80 girls from all over Pakistan by March next year.

For about US$540 each three-term semester, his students get room and board along with access to computers and the Internet, a luxury for some Pakistani schools.

It is a “game changer” in a region where religious conservative norms see many women keep some form of purdah — confined to women’s-only quarters at home — and “could only dream of coming out of their houses in the past,” says college vice principal Shama Javed.

Durkhanay and her classmates are confident the college will give them a fighting chance in Pakistan.

Affifa Alam, who wants to follow Farooq’s path and become an air force pilot, said the college represents a “big change.” “This will help us (in) realizing the dream of women’s empowerment,” she said.

From the last quarter of 2001, research shows that real housing prices nearly tripled (before a 2012 law to enforce housing price registration, researchers tracked a few large real estate firms to estimate housing price behavior). Incomes have not kept pace, though this has not yet led to defaults. Instead, an increasing chunk of household income goes to mortgage payments. This suggests that even if incomes grow, the mortgage squeeze will still make voters feel like their paychecks won’t stretch to cover expenses. The housing price rises in the last two decades are now driving higher rents. The rental market

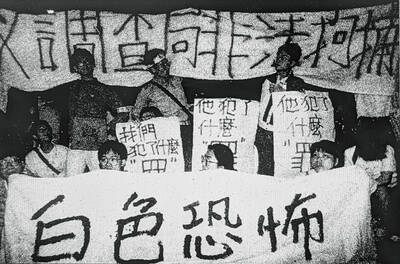

July 21 to July 27 If the “Taiwan Independence Association” (TIA) incident had happened four years earlier, it probably wouldn’t have caused much of an uproar. But the arrest of four young suspected independence activists in the early hours of May 9, 1991, sparked outrage, with many denouncing it as a return to the White Terror — a time when anyone could be detained for suspected seditious activity. Not only had martial law been lifted in 1987, just days earlier on May 1, the government had abolished the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of National Mobilization for Suppression of the Communist

Hualien lawmaker Fu Kun-chi (傅?萁) is the prime target of the recall campaigns. They want to bring him and everything he represents crashing down. This is an existential test for Fu and a critical symbolic test for the campaigners. It is also a crucial test for both the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and a personal one for party Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫). Why is Fu such a lightning rod? LOCAL LORD At the dawn of the 2020s, Fu, running as an independent candidate, beat incumbent Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) lawmaker Hsiao Bi-khim (蕭美琴) and a KMT candidate to return to the legislature representing

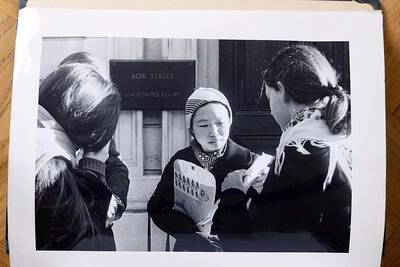

Fifty-five years ago, a .25-caliber Beretta fired in the revolving door of New York’s Plaza Hotel set Taiwan on an unexpected path to democracy. As Chinese military incursions intensify today, a new documentary, When the Spring Rain Falls (春雨424), revisits that 1970 assassination attempt on then-vice premier Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國). Director Sylvia Feng (馮賢賢) raises the question Taiwan faces under existential threat: “How do we safeguard our fragile democracy and precious freedom?” ASSASSINATION After its retreat to Taiwan in 1949, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) regime under Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) imposed a ruthless military rule, crushing democratic aspirations and kidnapping dissidents from