For decades the simple act of walking was largely overlooked by city planners but, no matter how you choose to get around your city, chances are that you are a pedestrian at some point during the day.

Recently, some cities have made great strides: from the ambitious public squares programs of New York and Paris to the pedestrianization of major streets (realized in the case of Stroget in Copenhagen; proposed in the case of London’s Oxford Street and Madrid’s Gran Via.)

Jeff Speck’s grandly titled General Theory of Walkability states that a journey on foot should satisfy four main conditions: be useful, safe, comfortable and interesting.

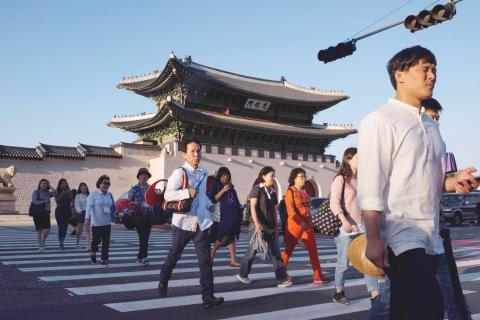

Photo: AFP

In his book Walkable City: How Downtown Can Save America, One Step at a Time, he argues that the “fabric” of the city — the variety of buildings, frontages and open spaces — is key.

US, Canadian and Australian cities, which were built for cars, have the challenge of retrofitting walking infrastructure.

Older European cities, which were built with walking in mind, have good fabric. This can make them walkable even if they lack pavements, crossings and other infrastructure for pedestrians — as is the case in Rome, says Speck.

“Rome, at first glance, seems horribly inhospitable to pedestrians,” he says. “Half the streets are missing sidewalks, most intersections lack crossings, pavements are uneven and rutted, disabled ramps are largely absent.”

Yet despite all this, as well as its hills and famously aggressive driving, this “anarchic obstacle course is somehow a magnet for walkers.” Why? Because Rome’s fabric is superb.

A NEW CITY RANKING

Walk Score, which lets prospective renters and buyers choose homes based on walkability, ranks cities in the US, Canada and Australia. New York tops the US list for this year at an overall 89 out of 100, with Little Italy and Union Square scoring full marks. San Francisco ranked second, followed by Boston. Vancouver, Toronto and Montreal rank from first to third respectively in Canada; while Australia’s most walkable cities are Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide.

New York famously began its urban transformation program in 2007, its flagship scheme the part-pedestrianization of Times Square two years later. The former transportation commissioner for New York City, Janette Sadik-Khan, said: “We changed the city from places people wanted to park to places people wanted to be — street space to seat space.”

“On 23rd St, where three streets meet, we created 6,000 square meters of public space. People choose to sit on the street rather than the park,” she said.

Like most transportation experts, Sadik-Khan believes walkability is about more than safety — it is about economic competitiveness, too.

According to the UN, well-planned cities should have 30 percent to 35 percent of their land dedicated to streets to get the benefits of high connectivity.

Manhattan scores 36 percent.

New York City is far from perfect, scoring third worst in an Inrix analysis of congestion from 1,064 cities in 38 countries, with commuters spending on average 89.4 hours a year stuck in traffic. But what was achieved in the city — first in showcase projects built quickly and with cheap materials like paint, benches and planters — opened people’s eyes to what was possible.

Sadik-Khan now works with city mayors around the world via NACTO (the US National Association of City Transportation Officials), recently publishing a tactical urbanism manual, Street Fight: Handbook for an Urban Revolution, to help other planners learn from her experience.

NACTO and Sadik-Khan’s work on the “Paris Pietons” program clearly draws a lot on New York’s example. By 2020, seven city squares will be redesigned, giving 50 percent more space to those on bike and on foot. The Place de la Republique was transformed from a roundabout back to a square in 2013.

“Opponents said it would be chaos, but it is not the case,” says Paris’ deputy mayor for transport, Christophe Najdovski.

“It is now a place where people can rest, where families with children and older people can come,” he says.

Under the “Paris-Plages” scheme, a former road space on the Seine and La Villette canal basin is turned into a “seaside” resort each summer.

Since the city first banned cars from parts of the Right Bank in 2002, the seasonal festival has expanded each year, and is now on both banks of the river.

Paris was made for walking, but cars have taken over, Najdovski says.

“You can walk from one end of Paris to the other in less than two hours,” he adds, “but historically the city had to adapt itself to cars.” The result: pollution and congestion. Now, walking is a “principal policy.”

In the words of Jan Gehl: “Life happens on foot. Man was created to walk, and all of life’s events large and small develop when we walk among other people. There is so much more to walking than walking. There is direct contact between people and the surrounding community, fresh air, time outdoors...”

ONE FOOT IN FRONT OF THE OTHER

Cities around the world are taking steps. Madrid introduced water fountains to help pedestrians cope with the hot summers. Medellin, in Columbia, built cable cars to link up poor neighborhoods with employment centers, introduced library parks and widened its pavements to encourage walking. Melbourne, in Australia, transformed unloved alleyways used primarily for rubbish into its now famous “laneways” buzzing outdoor seating for coffee shops and restaurants.

Guangzhou, in China, has among the highest levels of walking in the world.

Redevelopment of the banks of the Pearl river to create an ecological corridor has connected six paths, resulting in 96km of greenways, linking tourist attractions and sporting venues serving seven million people.

In May, Seoul opened its own version of New York’s High Line. Seoullo 7017 — an almost kilometer-long “sky garden” created from a 1970s motorway flyover — is the latest step in a bold plan to transform the city for pedestrians.

A decade earlier, the city’s Cheonggyecheon freeway, another four-lane elevated road, was torn down, and the dirty creek beneath reopened to the sky, its riverbanks to walkers.

London is moving forward too, with the proposed transformation of Oxford Street, where pedestrians have been crammed on to narrow pavements between queues of buses for decades. Next year, the street will become what Val Shawcross, the deputy mayor for transport, calls a “world-class pedestrian space,” with buses and taxis banished. The idea is to route buses to the street, rather than through it, as part of a project to cut traffic and encourage walking and cycling in the area, ahead of the Crossrail opening at the end of next year.

Some cities, like Dallas and Beijing, are going backwards, according to Mario Alves from the International Federation of Pedestrians.

As well as cities where a conscious effort has been made to improve conditions for people on foot, some cities are walkable because of their historic centers. There’s Florence in Italy, Vientiane in Laos, Kyoto in Japan — but the most striking is perhaps Fes el Bali, a walled section of Fez, Morocco’s second largest city.

Founded in the 9th century, it is believed to be the world’s biggest car-free zone, and its medieval streets are so narrow that rubbish is still collected by donkey. The beauty of the city, in terms of walkability, is its density: 156,000 residents live in an area just 3.5 square kilometers. As a result, almost all trips are by foot — and children can play on the streets.

May 18 to May 24 Pastor Yang Hsu’s (楊煦) congregation was shocked upon seeing the land he chose to build his orphanage. It was surrounded by mountains on three sides, and the only way to access it was to cross a river by foot. The soil was poor due to runoff, and large rocks strewn across the plot prevented much from growing. In addition, there was no running water or electricity. But it was all Yang could afford. He and his Indigenous Atayal wife Lin Feng-ying (林鳳英) had already been caring for 24 orphans in their home, and they were in

On May 2, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), at a meeting in support of Taipei city councilors at party headquarters, compared President William Lai (賴清德) to Hitler. Chu claimed that unlike any other democracy worldwide in history, no other leader was rooting out opposing parties like Lai and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). That his statements are wildly inaccurate was not the point. It was a rallying cry, not a history lesson. This was intentional to provoke the international diplomatic community into a response, which was promptly provided. Both the German and Israeli offices issued statements on Facebook

President William Lai (賴清德) yesterday delivered an address marking the first anniversary of his presidency. In the speech, Lai affirmed Taiwan’s global role in technology, trade and security. He announced economic and national security initiatives, and emphasized democratic values and cross-party cooperation. The following is the full text of his speech: Yesterday, outside of Beida Elementary School in New Taipei City’s Sanxia District (三峽), there was a major traffic accident that, sadly, claimed several lives and resulted in multiple injuries. The Executive Yuan immediately formed a task force, and last night I personally visited the victims in hospital. Central government agencies and the

Australia’s ABC last week published a piece on the recall campaign. The article emphasized the divisions in Taiwanese society and blamed the recall for worsening them. It quotes a supporter of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) as saying “I’m 43 years old, born and raised here, and I’ve never seen the country this divided in my entire life.” Apparently, as an adult, she slept through the post-election violence in 2000 and 2004 by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), the veiled coup threats by the military when Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) became president, the 2006 Red Shirt protests against him ginned up by