Located next to Sao Paulo, one of the world’s biggest cities, the Guarani-Mbya people’s reservation here was always easy to miss. Under a new law, it risks disappearing almost altogether.

“People think there aren’t any Indians in Sao Paulo,” says Antonio Awa, a community leader from the related Tupi-Guarani, with a smile.

The Jaragua reservation, just 20km from the Brazilian mega city, easily passes under the radar. The territory of 532 hectares, which was agreed to in 2015, doesn’t amount to much in this vast country.

Photo: AFP, Eraldo Peres

Last month, however, President Michel Temer tore up the agreement, meaning that the 720 members of the community will be left with one little corner that had been set aside in 1987 — just 1.7 hectares. Only one village of the current five would remain.

“The whites don’t understand our connection to the land because they don’t live in the forest,” said Tupa Mirim, one of Jaragua’s embattled inhabitants.

The village due to remain, Ytu, is in relatively good shape. In other villages, the Aboriginal people live in basic conditions, the children barefoot, the houses rudimentary and toilets shared.

Photo: AFP, Eraldo Peres

In Ytu, there’s running water in houses built by the state in the 1990s. There’s also the one health center and school for the community, where children learn their maternal Guarani until eight and then Portuguese.

But even here, there is a feeling that life is being squeezed out of the community.

Jurandir Karai Jekupe, 41, lost his infant daughter in June, when she was less than one. “The death certificate said it was because of a bacteria but no one explained to me what happened,” he says, noting that infant mortality is a constant worry on the reservation.

At the health center, which is open eight hours a day, respiratory infections are a common complaint, a nurse, who asked not to be identified, said.

“The center’s very small and not equipped to attend to the community in an adequate way,” said Thiago Karai, 22.

WHITE PERIL

Jekupe, a school teacher, said most of the shrinking community’s problems come from what the Guarani call “the whites” — the outside world.

That starts with the pollution and then the drought killing the local river Ribeirao de las Lavras. “We made a documentary about it but nothing changed,” he says sadly.

The Guarani also describe a plague of stray dogs and cats that they say were abandoned by outsiders. “It’s another problem brought by the whites,” Jekupe said.

Even though charity workers have sterilized the strays there are 480 dogs and almost half that number of cats.

In these changing times, surrounded by pressures of a culture they don’t want to be part of, the natives are discussing whether to remain part of a government anti-poverty program called the Bolsa Familia.

It helps, but “in our traditional way of life we don’t need money for food,” said another villager, Evandro Tupa. He said the money was creating dependency, a “bad habit,” especially for children.

Now the community councils are discussing the issue of Temer’s bid to shrink their territory.

Since this is a dispute resonating across Brazil’s Aboriginal lands, they hope to resist.

“Temer is not master of the land. If we unite, Temer won’t know what to do,” said Elizeu Lopes at a protest attended by community leaders.

“We were afraid at first, but we’re not going to take it lying down. We’ve been fighting for more than 500 years,” since colonization, said another, Tupa Mirim, 19.

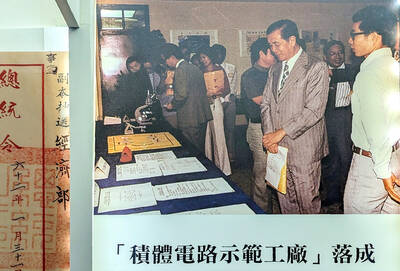

Oct. 27 to Nov. 2 Over a breakfast of soymilk and fried dough costing less than NT$400, seven officials and engineers agreed on a NT$400 million plan — unaware that it would mark the beginning of Taiwan’s semiconductor empire. It was a cold February morning in 1974. Gathered at the unassuming shop were Economics minister Sun Yun-hsuan (孫運璿), director-general of Transportation and Communications Kao Yu-shu (高玉樹), Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) president Wang Chao-chen (王兆振), Telecommunications Laboratories director Kang Pao-huang (康寶煌), Executive Yuan secretary-general Fei Hua (費驊), director-general of Telecommunications Fang Hsien-chi (方賢齊) and Radio Corporation of America (RCA) Laboratories director Pan

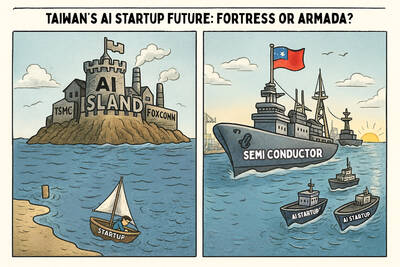

President William Lai (賴清德) has championed Taiwan as an “AI Island” — an artificial intelligence (AI) hub powering the global tech economy. But without major shifts in talent, funding and strategic direction, this vision risks becoming a static fortress: indispensable, yet immobile and vulnerable. It’s time to reframe Taiwan’s ambition. Time to move from a resource-rich AI island to an AI Armada. Why change metaphors? Because choosing the right metaphor shapes both understanding and strategy. The “AI Island” frames our national ambition as a static fortress that, while valuable, is still vulnerable and reactive. Shifting our metaphor to an “AI Armada”

The older you get, and the more obsessed with your health, the more it feels as if life comes down to numbers: how many more years you can expect; your lean body mass; your percentage of visceral fat; how dense your bones are; how many kilos you can squat; how long you can deadhang; how often you still do it; your levels of LDL and HDL cholesterol; your resting heart rate; your overnight blood oxygen level; how quickly you can run; how many steps you do in a day; how many hours you sleep; how fast you are shrinking; how

“‘Medicine and civilization’ were two of the main themes that the Japanese colonial government repeatedly used to persuade Taiwanese to accept colonization,” wrote academic Liu Shi-yung (劉士永) in a chapter on public health under the Japanese. The new government led by Goto Shimpei viewed Taiwan and the Taiwanese as unsanitary, sources of infection and disease, in need of a civilized hand. Taiwan’s location in the tropics was emphasized, making it an exotic site distant from Japan, requiring the introduction of modern ideas of governance and disease control. The Japanese made great progress in battling disease. Malaria was reduced. Dengue was