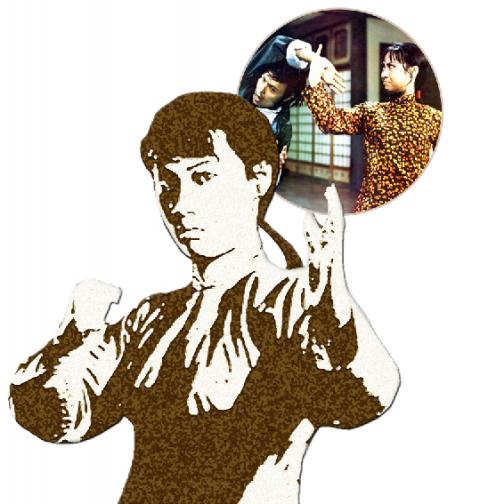

At the reception for an Asian film festival at Lincoln Center six years ago, excitement rippled through the crowd: Was it her? Lady Kung Fu? Was that Lady Whirlwind?

Rumors long circulated that she had left movie stardom in Hong Kong for domestic life in New York City, but no one had heard much else about Angela Mao (茅復靜), possibly the most famous martial arts actress of her time, in more than 30 years.

Surprised fans were now greeted by a small 60-year-old woman wearing a floral silk dress. Her son helped her manage the crowd. One fan, Ric Meyers, approached her for a photo. Like others, he was curious to know what she had been up to. He got his answer.

“She told me and my friends she was running restaurants in Queens,” Meyers said. “I told them, ‘We all have to go.’ But we all just got too busy and never went.”

“She gave off the impression,” he added, “that she was a very private person.”

RESTAURATEUR

On a warm afternoon in September, Mao, now 66, sat in one of those restaurants, keeping an eye on lunch service as she rubbed her baby granddaughter’s belly.

The restaurant, Nan Bei Ho, sits on a quiet street in Bayside, a suburban Queens neighborhood beyond the reaches of the subway system and not far from the Long Island border. It is the oldest of three restaurants she runs with her husband and son, all of them in Queens. It serves Taiwanese food and is popular on weekends but is otherwise nondescript.

Martial arts fans have sought the address of this restaurant for some time — they wanted to know what happened to Angela Mao, the Queen of Kung Fu, who fought and flew through dozens of films in the 1970s but vanished within a decade.

A woman with a hearty laugh, Mao sometimes expressed confusion that people still had any interest in her.

Over the course of three hours at the restaurant, she spoke in Mandarin, with her son and his wife translating into English. Mao, who usually declines interviews, reflected on her past without sentimentality.

“How famous was I?” she said. “When I was a somebody, Jackie Chan (成龍) was a nobody.”

Mao’s career was brief but bright, taking place in Hong Kong and Taiwan and including roles in more than 30 films over a decade. Studios promoted her as a female Bruce Lee (李小龍). When she appeared as Lee’s doomed sister in the 1973 martial arts classic Enter the Dragon, her place in the kung fu canon was secured. Quentin Tarantino has cited her as an influence, and a violent fight scene in his 2003 film Kill Bill involving a swinging ball and chain is strikingly similar to one of Mao’s duels in Broken Oath.

She fought with ferocity and grace, mowing through armies of opponents with jaw-breaking high kicks, interrupting the carnage only to flip her pigtails to the side. She was born Mao Ching Ying in 1950 and grew up in Taiwan, the third of eight children, to a family of entertainers for the Peking Opera House. Like her siblings, she started training for the opera at a young age, taking voice lessons when she was five. She also studied martial arts, specifically hapkido, rising to the level of black belt — a prowess that later distinguished her from other action stars, who merely choreographed their fight scenes.

HONG KONG YEARS

In her 20s, she moved to Hong Kong, where a thriving film industry was based, but she was hardly romantic about it.

“To be honest, the money was just better in movies,” she said. “I had to support my family. Most of the money I made I gave to them. This is the Chinese tradition.”

Her break came when the Hong Kong producer Raymond Chow (鄒文懷) discovered her in an opera. Though Mao generally described her life as a case of being in the right place at the right time, she did display a rare moment of tenderness at this point. “I have to thank God and Raymond Chow,” she said.

The dominant studio in Hong Kong at the time was Shaw Brothers, which produced dozens of formulaic action films per year. Chow was considered one of Asian cinema’s revolutionaries for founding the competing studio, Golden Harvest, which is credited with helping bring martial arts cinema to the West. Among his early coups were signing Bruce Lee — and discovering Angela Mao.

“Everyone told him, ‘No one wants to see a woman on the screen,’” Meyers said. “He said, ‘That’s not true: I do.’ And Raymond Chow was right. He searched for a female actress with the same charisma and talent as Bruce Lee, and he found Angela Mao.”

Her first prominent role was Hapkido, or Lady Kung Fu, in 1972. “That made me a star,” she said. “I traveled the world to promote it. People knew my face. Then the whole Asian world knew my face.” Lady Kung Fu, along with Lady Whirlwind, also in 1972, established her nicknames.

In the early 1970s, she appeared in a string of films now considered martial arts classics: Angry River, Thunderbolt, The Fate of Lee Khan, When Taekwondo Strikes and The Tournament. A teenage Jackie Chan appeared as an uncredited stuntman in several of her early films.

Aside from some cameos in the early 1990s, Mao said, she effectively concluded her film career in 1983, when her son was born. By this time, her husband had moved to New York to start a construction company. Mao and their son joined him in 1993. She opened her first restaurant, Mama King, on Roosevelt Avenue in Flushing three years later. She opened Nan Bei Ho in 1997. New Mei Hua, in Flushing, and Guo Ba Inc, in Bayside, would follow.

“After I got married,” she said, chuckling, “I had to keep a lower profile so my husband could be the leader. But in film? I was the king.”

Mao’s lack of regard for stardom may have been apparent from the start. “It is evident that success has not spoiled Angela Mao, or that she is too simple to know the extent of her popularity,” a 1974 profile in a martial arts magazine reads. “But, there is a small indication she is finding all the strings of kung fu movies a bit monotonous since she constantly repeats her plans after retirement. She still considers herself Mao Ching Ying, the Chinese opera actress and loves simple clothes.”

The article ends: “Angela Mao gets up to leave. She runs her hands down the sides of her Levi’s, crushes a last Silva Thin on an ashtray and picks up her purse... She did not say goodbye.”

If Mao has tried to part ways with her past, she has never been able to fully shake it. The occasional customer recognizes her to this day, and sharp-eyed kung fu fans still stop her in the street.

“It always happens,” Mao said. She recalled the time years ago when, while she was sitting in Central Park, a man shouted “That’s Angela Mao!” “He wanted to know what it was like working with Jackie Chan,” she said. “I was so surprised.”

KUNG FU PIONEER

Meyers considered her legacy. “She didn’t have the ego of Bruce Lee,” he said. “He didn’t feel justified unless he was a star. She didn’t need that. She left Hong Kong on her own terms. She was a pioneer unconcerned with her own stardom.”

May Joseph, a professor at Pratt Institute who wrote an essay about Mao as a feminist hero, encapsulated her influence this way: “She was a radical feminist cinematic presence before there was a language for that,” she wrote in an e-mail. “She is the Lauren Bacall of kung fu.”

Mao, however, bristled at grandiose notions about her legacy; she was not interested in hearing that she had become the subject of feminist literature.

“This is not a gender situation,” she said with a baffled expression. “I just played myself. I am strong and I am powerful. That is how I became the most important female kung fu actress of my time.”

One story told in kung fu circles is that she was paid only $100 for her role in “Enter the Dragon.” The subject obviously fatigued her. “I’m more focused on the quality of the movie than how much money I got paid,” she said. “I am very traditional. I don’t want to argue for special things. I don’t think much about male power and female power.”

Grady Hendrix, a founder of the film festival at Lincoln Center who endured the challenge of tracking her down, suggested that Mao was part of a bigger story.

“She’s one of those martial arts ‘What happened to?’” Hendrix said. “Lots of Hong Kong talent ends up in places like New York or Vancouver. One of the ‘Five Deadly Venoms’ had a kung fu academy in New York. For every Jackie Chan, there’s ones that aren’t.”

As evening approached at Nan Bei Ho, Mao seemed to have had enough of reminiscing. While her family and staff took a break to feast on barbecued meats in celebration of an autumn Chinese festival, she fed mashed potato on a soup spoon to her granddaughter. Later, she chopped snails in the kitchen to make a soup for her son, George King.

Over the years, King, 33, has become his mother’s reluctant point man, handling occasional inquiries from kung fu pilgrims who track down his cellphone number. He shares her indifference to the past. “I just don’t think about it,” he said. “That generation thought about things differently. I think she was just blind to gender inequality. She was too busy working to support her family.”

The primaries for this year’s nine-in-one local elections in November began early in this election cycle, starting last autumn. The local press has been full of tales of intrigue, betrayal, infighting and drama going back to the summer of 2024. This is not widely covered in the English-language press, and the nine-in-one elections are not well understood. The nine-in-one elections refer to the nine levels of local governments that go to the ballot, from the neighborhood and village borough chief level on up to the city mayor and county commissioner level. The main focus is on the 22 special municipality

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invaded Vietnam in 1979, following a year of increasingly tense relations between the two states. Beijing viewed Vietnam’s close relations with Soviet Russia as a threat. One of the pretexts it used was the alleged mistreatment of the ethnic Chinese in Vietnam. Tension between the ethnic Chinese and governments in Vietnam had been ongoing for decades. The French used to play off the Vietnamese against the Chinese as a divide-and-rule strategy. The Saigon government in 1956 compelled all Vietnam-born Chinese to adopt Vietnamese citizenship. It also banned them from 11 trades they had previously

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful