Taiwan in Time: March 14 to March 20

On May 11, 1985, student protesters marched through the National Taiwan University (NTU) campus shouting “general elections (普選)” and “I love NTU.”

Mirroring the era’s national political situation, only class representatives could vote for student president. School officials tried to stop the students, who had been calling for direct elections since 1982, but after some fierce arguing, the students went ahead with the plan.

Photo: Tang Chia-lin, Taipei Times

Taiwan was still under martial law and public gatherings were illegal. Students were handed demerits by the school and nothing would change for a few more years.

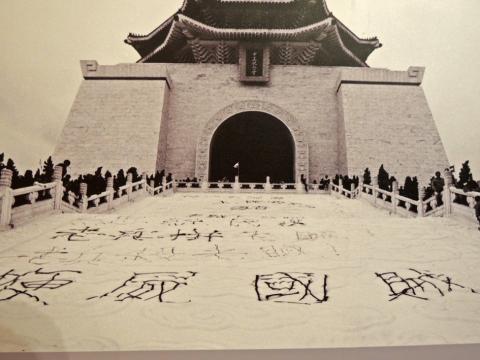

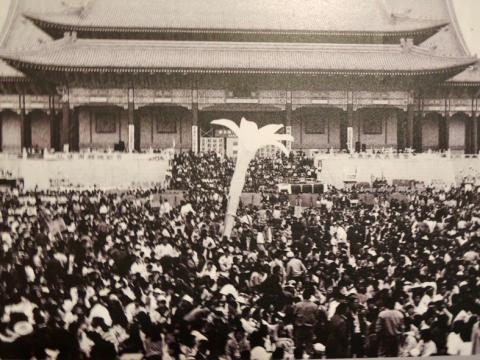

But this event marked the first open student operation after years of simmering campus unrest. It started with the clandestine circulation of flyers about free speech in 1981 and culminated in the massive Wild Lily Student Movement (野百合學運), where students occupied Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Square (today’s Liberty Square) from March 16 to March 22, 1990.

For decades, campus voices had largely been silent. Student protests over police brutality on April 6, 1949 led to mass arrests and several alleged executions.

Photo: Tang Chia-lin, Taipei Times

When martial law was declared a month later, which lasted 38 years, schools were militarized and all activities placed under strict government control as the country hurtled towards the dark years of the White Terror era.

THE TIMES THEY ARE A CHANGIN’

Teng Pi-yun (鄧丕雲) writes in his book, A History of Taiwan Student Movements in the 80s (80年代台灣學生運動史) that although school activities were still heavily monitored in the late 1970s, the political situation was changing with the rise of the dangwai (黨外, outside the party) movement and its publications critical of the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) one-party rule, which were often passed around in secret on campus.

During the early 1980s, campus activism was limited to unorganized small groups who called for more freedom of expression through underground posters, graffiti and campus rallies and speeches. Off-campus, some students helped with dangwai campaigns and activities — but faced punishment if their schools found out.

“The biggest difference [before martial law was lifted] was the high level of risk that came with any type of activity,” Teng writes. “Student activists faced a great deal of uncertainty, not knowing what would happen to them.”

But it was no longer the 1950s, and most of the time students just received warnings, demerits and, at worst, expulsion.

Meanwhile, student publication staff were in frequent conflict with school officials, who had to approve all output beforehand. Many publications were suspended, shut down or restructured for bypassing the censor or writing “inappropriate” commentary. This led to the proliferation of underground publications such as National Central University’s Wildfire (野火) and NTU’s Love for Freedom (自由之愛).

Kuo Kai-ti (郭凱迪) writes in a study of Taiwanese student movements that the staff at these publications felt government suppression most directly, and often became the first to take part in student movements.

Teng writes that the first organized movement with a clear objective took place in September 1982, when several NTU clubs banded together before the student government elections and called for change to the system. With their publications censored and activities blocked, the members mostly operated by privately distributing brochures and fliers, including one that appeared on election day that urged the class representatives to boycott the election.

School punishments didn’t deter this emerging revolutionary spirit, as students and school authorities fought back and forth throughout the early 1980s, and by the protests of 1985, it had gone from covert operations to open gatherings. There was no going back.

EXPANDING INTERESTS

Taiwan’s political climate changed dramatically in the second half of the decade, most significantly with the lifting of martial law in 1987. Activists expanded their interests from school affairs to social issues and partook in environmental protection and farmers’ rights movements.

Teng writes that this fervor boiled over to politics relatively late, and started with students challenging campus norms such as inviting members of the opposition movement to speak and holding memorials and forums for the long-suppressed 228 Incident.

Pro-independence student groups would later stage silent protests after independence activist Deng Nan-jung (鄭南榕) self-immolated in 1989, and others provided support for political candidates for elections.

“These activities were like a warm-up for the events to come,” Teng writes.

Tension rose as the March 1990 presidential elections approached. Even though martial law was over, people were still not allowed to vote as the KMT-only candidates were nominated and voted in by members of the National Assembly. These “representatives” were supposed to be popularly elected — but there hadn’t been an election since 1947, earning them the moniker “Ten-thousand year congress (萬年國會).”

Reminiscent of how they stood up against the NTU election system in 1985, students this time took to the national stage, calling for political reform and true democracy as they marched into what is today Liberty Square.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand