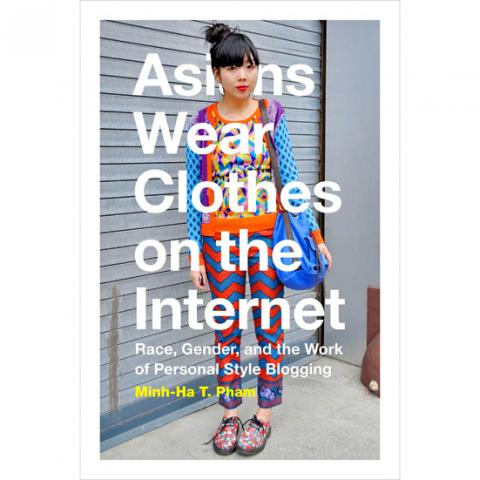

This is a book about a Filipino who calls himself “Planet Earth’s favorite third-world fag” and a Chinese-American who hides her face in her photos because she thinks her eyes are ugly. Both have had their “signature” poses replicated by celebrities in advertisements for some of the world’s fashion icons such as Marc Jacobs. Both have massive followings for, well, wearing clothes on the Internet. They are among an elite group of Asian personal-style “super bloggers,” as Minh-Ha Pham calls them, in this study of race and gender in the world of online fashion blogging.

Pham says that Asians, especially females, occupy two extremes of the clothing industry: the numerous garment factory workers around the world often performing repetitive tasks under what we don’t like to call sweatshop conditions, and the bloggers such as Susanna Lau (Susie Bubble), Aimee Song and Bryan Yambao (BryanBoy).

Pham’s book, which takes a scholarly approach to phenomena we run across everyday on the Internet such as mirror selfies and fashion blogger poses, argues that, on the surface, the rise of Asian bloggers heralds a “racial democratization” of the fashion world and signifies that people of any background can have a piece of the (still) Caucasian-dominated industry. However, she says it’s an illusion that obfuscates persisting racial stereotypes existing since Asians started moving to the West.

What these bloggers are doing may be simple (hence the ultra-straightforward book title) but as the subtitle suggests, there is much to discuss and think about along racial, social and financial lines. Just as how the photos these bloggers produce of themselves completely conceal all the work that goes into making being fashionable seem “effortless,” Pham writes that when race is “embedded in digital technology and practices,” sometimes it becomes invisible to human perception.

The book starts from the global social, technological and financial conditions that led to this phenomenon, to how bloggers write, pose, assume certain gender and racial roles all while providing a look into the sociological mechanisms of the “participatory culture” of the Internet. The language, since it’s an academic work, can be dense and repetitive at times as Pham tries to reinforce her points — which could be conveyed in much shorter length — but overall it’s not a difficult book to understand.

Pham sees the Asian blogger phenomenon as one of many paradoxes. As much as it is an opportunity for Asians, she still finds parallels between the blogger and the garment worker, which loosely becomes the central theme of the book.

Is this phenomenon actually empowering Asians and giving them unprecedented opportunities, or are they still being exploited by the system under the guise of multiculturalism? Pham doesn’t have all the answers, but she provides a pretty thorough analysis, as far as explaining why Asians have been successful in the field so far.

It’s worth noting that despite their success, it’s just a tiny add-on to the fashion industry as a whole, which is still Caucasian-dominated. Pham writes that while these Asians are able to use their racial differences (and even stereotypes) to their advantage amid the increasing global popularity of Asian culture and emerging Asian luxury markets, they still have to play by the rules.

One of the more intriguing points of the book is the degree of “differentness” that a minority can display without making the majority feel uncomfortable or threatened. While these bloggers look Asian and express certain traits that are perceived as Asian such as “cuteness,” they are fluent in English, attuned to Western culture and are relatable enough that the majority would follow and even mimic them.

While the hows are explained well, some of the racial explanations for certain behavior feel like borderline over-analysis, especially when you’re writing about a very select group of individuals. While most of Pham’s arguments make sense on a logical level, at times it left me wondering if I am really that oblivious to certain racial injustices carried out by the majority or whether Pham is simply reading too much between the lines.

For example, she attributes certain phenomena to the bloggers being Asian — such as how they conceal the work that goes into making a blog post to counter the sweatshop stereotype — but really, this type of action is universal in the blogosphere regardless of race, as people in today’s instant-gratification Web culture probably wouldn’t want to see photos of them shopping or editing their photos. They just want the end product.

There are a few mainstream articles Pham sees as singling out Asian bloggers as tacky, unethical and trying too hard, but as she mentions throughout the book, the original and most prominent fashion bloggers are Asian, so they could naturally make for an easy target. If there were any counterexamples of Caucasian bloggers and media coverage of them, the argument would be stronger, but unfortunately the book barely mentions any, which is another glaring problem.

“Why does Taiwan identity decline?”a group of researchers lead by University of Nevada political scientist Austin Wang (王宏恩) asked in a recent paper. After all, it is not difficult to explain the rise in Taiwanese identity after the early 1990s. But no model predicted its decline during the 2016-2018 period, they say. After testing various alternative explanations, Wang et al argue that the fall-off in Taiwanese identity during that period is related to voter hedging based on the performance of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Since the DPP is perceived as the guardian of Taiwan identity, when it performs well,

The Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on May 18 held a rally in Taichung to mark the anniversary of President William Lai’s (賴清德) inauguration on May 20. The title of the rally could be loosely translated to “May 18 recall fraudulent goods” (518退貨ㄌㄨㄚˋ!). Unlike in English, where the terms are the same, “recall” (退貨) in this context refers to product recalls due to damaged, defective or fraudulent merchandise, not the political recalls (罷免) currently dominating the headlines. I attended the rally to determine if the impression was correct that the TPP under party Chairman Huang Kuo-Chang (黃國昌) had little of a

At Computex 2025, Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang (黃仁勳) urged the government to subsidize AI. “All schools in Taiwan must integrate AI into their curricula,” he declared. A few months earlier, he said, “If I were a student today, I’d immediately start using tools like ChatGPT, Gemini Pro and Grok to learn, write and accelerate my thinking.” Huang sees the AI-bullet train leaving the station. And as one of its drivers, he’s worried about youth not getting on board — bad for their careers, and bad for his workforce. As a semiconductor supply-chain powerhouse and AI hub wannabe, Taiwan is seeing

Jade Mountain (玉山) — Taiwan’s highest peak — is the ultimate goal for those attempting a through-hike of the Mountains to Sea National Greenway (山海圳國家綠道), and that’s precisely where we’re headed in this final installment of a quartet of articles covering the Greenway. Picking up the trail at the Tsou tribal villages of Dabang and Tefuye, it’s worth stocking up on provisions before setting off, since — aside from the scant offerings available on the mountain’s Dongpu Lodge (東埔山莊) and Paiyun Lodge’s (排雲山莊) meal service — there’s nowhere to get food from here on out. TEFUYE HISTORIC TRAIL The journey recommences with