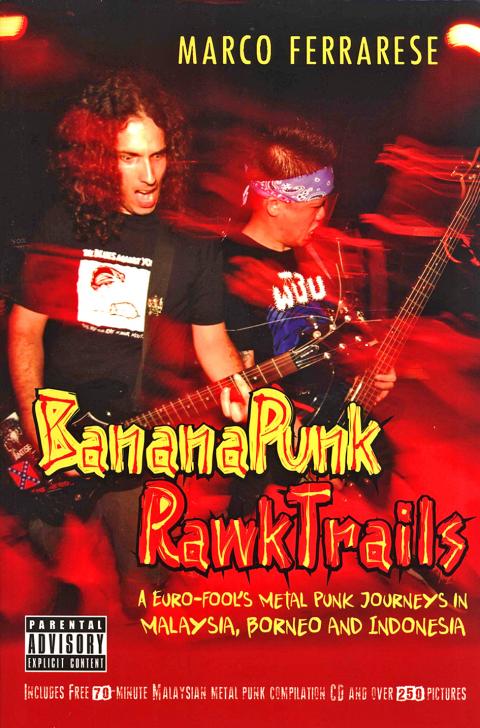

Marco Ferrarese is an extraordinary phenomenon, a veritable polymath who will one day figure in Malaysia’s literary heritage. He’s Italian, born in Voghera, by his own description long-haired and with “colorful tattoos crawling out of my singlet” and a guitarist. He lives in Penang where he plays in a heavy metal band. But he has also taught Italian in Qinhuangdao, China, and is about to present a doctoral thesis to Australia’s Monash University, which has a campus in Kuala Lumpur. As if this wasn’t enough, he also publishes books in English, of which Banana Punk Rawk Trails is the second.

His first, Nazi Goreng, was a novel about drug-running in Penang. As soon as it was translated into Malay last year it was banned. In my enthusiastic review of it [Taipei Times March 6, 2014], I said it would be nice to read more about Ferrarese’s musical experiences, and this is precisely what he’s come up with in this excellent new book.

If more of this review than usual consists of quotations, it’s because I’m not conversant with the music the author deals with, and he has in fact provided me with a welcome education in the subject. As for the compilation CD featuring Malaysian metal bands that comes free with the volume, I found it hard to listen to. But that’s a feature of my age and cultural background, and is anyway another story.

What this book is keen to present is a youth movement that’s anxious to express anti-establishment attitudes, that is heavily indebted to Western models, but whose members at the same time remain unswervingly devoted to their religious beliefs and practices.

As I say, I learned a lot — about a Canadian “electro-industrial” band called Skinny Puppy who filed a royalties bill with the US Department of Defense after learning their music had been used to torture prisoners at Guantanamo Bay; the sum claimed was US$666,000 (“nice number,” comments Ferrarese). We meet people with names like Aerick Lostcontrol and discover what a Malaysian “Ramly Burger” is. And the black-and-white photos, some 250 of them, are highly atmospheric, making you want to jump on the next plane bound for East Malaysia or Indonesia forthwith.

And the most interesting part of the book is indeed that describing touring in Indonesia and East Malaysia. He goes with his Penang-based band, WEOT SKAM, standing for “We express ourselves through skateboarding and music.” Malaysian Borneo, a “sadly over-logged land,” proves very different from the peninsula. Sarawak and Sabah, Ferrarese claims, are “two states where racial harmony truly exists,” with “no trace of West Malaysia’s racist nutters.”

Traditions are largely Iban in Kuching, for example, with several female-fronted metal bands in evidence, and plenty of females at gigs, contrasting in both cases with the peninsula. East Malaysia’s musically different too, with Indonesian bands preferred to West Malaysian ones. In fact Ferrarese detects a pan-Borneo mentality generally, with Pontianak, capital of Indonesia’s West Kalimantan region, a “punk metal heaven.”

Joko Widodo is described as “Indonesia’s — and the world’s — first heavy metal president,” on the grounds of his love for the music. The favorite Indonesian forms, we learn, are “grindcore, crust, d-beat, black metal and death metal,” and Indonesia is the only South-east Asian country with its own edition of Rolling Stone, published in Jakarta in the local language.

Throughout this book, Marco Ferrarese shows himself to be both knowledgeable and critically alert. He talks about black metal’s “fierceness and belligerent attitude,” cites Malaysian metalheads who changed their Facebook profile pictures to ones showing them with him, even though most were “busier toying with their smart phones than actually talking to me,” and critically describes one Kota Kinabalu soloist as “bursting out his throat-ripping, growling screams,” even though Ferrarese himself performed a “wild stage act” with his original band, The Nerds Rock Inferno, once slashing his forehead and splashing the stage with blood.

Who would have known about Java’s heavy metal scene if Ferrarese hadn’t been there and told us? Yet he manages to combine this dispassionate objectivity with a no-holds-barred devotion to the music. As for his former Nerds band, who he played with from 1997 to 2007, playing in almost every US state in the process, when he re-joins them to tour Malaysia in 2014, he writes “We were … inbred sons of the rawest old-school black metal and the fastest, most unhinged garage punk, sealed into a hardcore punk iron fist all through.”

Yet this extraordinary man can also pen a doctoral thesis about, as he told me in an e-mail, “extreme music identity formation in multi-ethnic, multi-religious Malaysia,” arguing that “hybrid forms do not necessarily take on a ‘third form’ because sediments of pre-existing identities hamper the process,” making the meaning of these subcultures “re-negotiable and changing, albeit remaining fixed to globally established performance codes.”

But don’t expect this marvelous book to contain anything like that. Instead, you find witty phrasing (penned in a foreign language, remember) such as “the path less trudged,” Western guidebooks herding backpackers “like confused cattle,” “blood, sweat, tears and beers,” preachers of a “chainsaw punk gospel,” and a “smile that feels as fake as a prostitute’s orgasm.”

This book, then, is both a record and a celebration. Basically, Ferrarese sees the music as carnivalesque, a form of entertainment and a playful rebellion (all his terms). We tour with WEOT SKAM as far east as Bali (not Ferrarese’s favorite place), hear of the influence of Nirvana before they “got kissed by the pouty lips of mainstream stardom,” relish Singapore’s Impiety (“unarguably the most celebrated black metal band in Southeast Asia”), and are infused with admiration for an author who, incredibly, hitch-hiked from Penang to Italy in 2012.

Hitch-hiked? Would any former literary specialist in Malaysia, such as Somerset Maugham or Anthony Burgess, have done that? Or played cacophonous music, and then written a PhD, as well as a superb book, about it? No way. I was dumbfounded. Ferrarese represents a refusal of all old-style compartmentalizations. Kerouac is his only forebear. But what a scene! What a man! What a book!

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

When the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese forces 50 years ago this week, it prompted a mass exodus of some 2 million people — hundreds of thousands fleeing perilously on small boats across open water to escape the communist regime. Many ultimately settled in Southern California’s Orange County in an area now known as “Little Saigon,” not far from Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton, where the first refugees were airlifted upon reaching the US. The diaspora now also has significant populations in Virginia, Texas and Washington state, as well as in countries including France and Australia.

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with