Jekyll + Hyde,

Zac Brown Band,

Southern Ground/John Varvatos/Big Machine/Republic

Ever since 2008, when the Zac Brown Band made its first overtures toward the country mainstream, it has stealthily tried to remake the genre from within. Extremely facile, with tendencies somewhere between bar band and jam band, it was able to pass for conventional country on early hits like Chicken Fried and Toes. But live concerts revealed something else entirely: a formidable, flexible country-rock outfit in search of bigger stages.

But as those stages became larger, the Zac Brown Band became less interesting. Brown is, at best, a meaty, un-nuanced singer, and the less complex the song, the fewer places he had to hide. The group shined on ballads like Highway 20 Ride and Goodbye in Her Eyes, but when it skimped on thick emotion, it had little to recommend itself.

As the Zac Brown Band churned, mainstream country was changing, finally. For the group, that was a win and a loss: Country has become more diverse and open-eared, but not necessarily in ways that benefit the Zac Brown Band.

The amiable Jekyll + Hyde, its fourth major-label full-length album, suggests a path forward. Rather than follow the hip-hop hybrids of the day, the album offers a huge amalgam of soft rock, country-rock, hard rock, heavyish metal, big band music, bluegrass and, yes, a touch of electronic music.

Jekyll + Hyde is the sort of album that giddily puts a song featuring Sara Bareilles back to back with one featuring Chris Cornell, the kind of omnivorousness that went in and out of fashion in hip-hop more than a decade ago, but still feels novel in country. On the Bareilles song, Mango Tree, Brown turns into lounge singer over an unremarkable big band arrangement that concludes with a battering ram of horns. On the Cornell song, Heavy Is the Head, Brown finds something approximating a rock growl, though not a tough one. (The same is true on the mystifying Junkyard.)

On songs like Loving You Easy and Young and Wild, Brown’s most familiar mode might comfortably be called nu-Chesney, a revisiting of the beach-friendly sounds that qualified as radical a decade ago. On the island tour of Castaway, Brown just shrugs and goes the full nu-Buffett.

Those modes serve him well. His unimaginative voice can gum up a song, as it does here on Dress Blues, and he rarely moves past lyrical platitudes. When he evokes Kenny Rogers, as on One Day, it’s effective, but more often it’s a liability. As in the past, he’s best when excavating deep feelings. Bittersweet is about learning a loved one is about to die, and facing the impending tragedy with an open heart, and surviving it.

Even when Brown is taking it easy, though, the band is working hard, eager to show it’s trapped inside a flimsy box. Take the Celtic-ish blues of Remedy or Tomorrow Never Comes, a lightly gothic electronic-music-inflected bluegrass song, and one of the album’s most exciting.

But for every song that issues a challenge, there are two that play nice. And there are nods to what are perceived as mainstream country values, like Dress Blues, about a young soldier who dies at war, which concludes with a messy violin rendition of Taps. The band tries to bend it into a shape that suits its own agenda, but even so, it’s a poor fit.

— Jon Caramanica, NY Times News Service

Who Is the Sender?

Bill Fay,

Dead Oceans

If you’re interested in new pop that does not follow the current media discourse, that is gentle to the point of frailty, that prophesies but never quite disturbs, Bill Fay might be your man. New needs a qualification: Who Is the Sender is indeed a collection of new songs, but right out of the wrapper, they feel aged almost to the point of expiration.

Fay is a figure of minor interest from the English folk-rock scene of the early 1970s. His first studio album of new material came out in 1970, his second in 1971, and his third, Life Is People, more than 40 years later, after a belated rediscovery by Jim O’Rourke, Jeff Tweedy of Wilco, and others who covered his songs. Who Is the Sender more or less qualifies as his fourth album, outside of some demos and home recordings.

In his songs, he is a small figure in the universe, a watcher of nature, human and ecological. He sits at his piano, singing slow, whispery, post-nuclear homilies and observations of man’s folly, and almost dares you to ignore him.

The tremulous voices of aging Londoners achieve an almost cinematic piquancy when they are hoping for the best. This is essentially what Fay does, adding a bit of Christian mysticism, to the tune of folk-rock, hymns, and canons. He sounds utterly post-anger. (At times this record, produced by Joshua Henry, with occasional strings, brass, organ and electric guitar, recalls the atmosphere of Randy Newman’s Sail Away, but without the barbed lyrics.) His is not the sound of a man who needs to be heard, but he is saying things that ought to be said. In other words, he makes you feel empathy — not quite the same as stimulation or excitement.

Now as before, Fay’s observations are basically anti-a la mode. He is at the purest point of his mission, really, when intoning something simple over and over again: “It’s all so deep,” eight times in a row in How Little. Or “This can’t be all there is,” four times in World of Life.

But he also makes you consider where prophecy stops and truism begins. “There’s an age up ahead,” he sings on A Page Incomplete, that is “out of reach of this one’s grip.”

You can’t say he’s wrong. You can’t say this needn’t be pointed out. And such is the case for most of this record. It means well and conjures fellow feeling and makes you think the long thoughts. But it is a trudge, and strangely ponderous in its smallness.

— Ben Ratliff, NY Times News Service

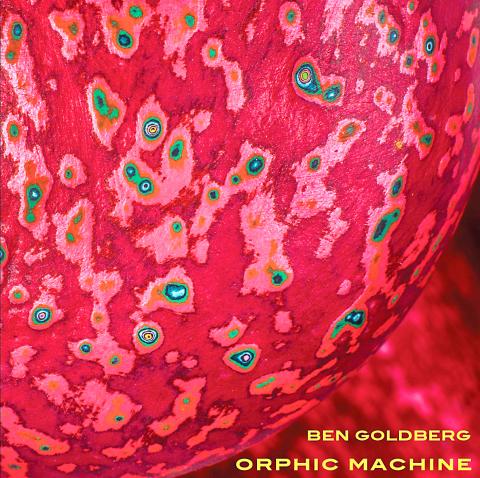

Orphic Machine,

Ben Goldberg,

BAG

The high degree of difficulty on Orphic Machine, an enveloping new album by the clarinetist Ben Goldberg, has little to do with the formal intricacy or catalytic chemistry in his music.

The challenge comes from Goldberg’s inspiration for the album: Summa Lyrica: A Primer of the Commonplaces in Speculative Poetics, a book-length essay by Allen Grossman.

An influential work of poetic theory ever since its publication more than 20 years ago, it’s hardly a natural candidate for a musical adaptation. But Goldberg, who had Grossman as an undergraduate professor in the late 70s, brings a light touch and a soulful ear. There’s little that rings emotionally heavy here, even though Grossman’s death last year at 82 imparts a whiff of elegy to this music.

Goldberg marshals some of the sharpest improvisers on the scene into a dynamic orchestra. Carla Kihlstedt, his fellow member of the style-blending chamber group Tin Hat, takes center stage through most of Orphic Machine, singing verses excerpted from the original text. That it works so bewitchingly is a testament to Kihlstedt’s cool-headed, unflashy singing, and to Goldberg’s graceful way with a melody. On Immortality, they even bring a sly sensuality to the first line of Grossman’s argument: “The function of poetry is to obtain for everybody one kind of success at the limits of the autonomy of the will.” (Yes, somehow it works.)

Besides Kihlstedt, who also plays violin, Orphic Machine features the trumpeter Ron Miles and the tenor saxophonist Rob Sudduth, blending or jostling by turns with Goldberg’s woodsy clarinet. The rhythm section consists of Nels Cline on electric guitar, Kenny Wollesen on vibraphone, Myra Melford on piano, Greg Cohen on bass and Ches Smith on drums.

On a piece like Care, the ensemble floats from one clear melodic premise to the next, never sounding overdetermined or strained. The title track begins in rustling pianistic reverie, turns into a kind of soul dirge, shifts into oblique art song with classical counterpoint, and finally succumbs to a crushing accumulation of distorted guitar: all of it unpredictable, most of it thrilling.

More than anything, Goldberg seems to have taken at face value, with imaginative care, his former teacher’s note in the essay’s preface: “Above all,” he writes, “this is a text for use, intended like a poem to rise to thoughts about something else.”

— Nate Chinen, NY Times News Service

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Toward the outside edge of Taichung City, in Wufeng District (霧峰去), sits a sprawling collection of single-story buildings with tiled roofs belonging to the Wufeng Lin (霧峰林家) family, who rose to prominence through success in military, commercial, and artistic endeavors in the 19th century. Most of these buildings have brick walls and tiled roofs in the traditional reddish-brown color, but in the middle is one incongruous property with bright white walls and a black tiled roof: Yipu Garden (頤圃). Purists may scoff at the Japanese-style exterior and its radical departure from the Fujianese architectural style of the surrounding buildings. However, the property