Researchers at Pegatron Corp (和碩), best known as a manufacturer of iPhone components, have produced a small electronic device that allows blind children to practice Braille on their own.

“The children we’re thinking about are from low-income families. This is an automated teaching device that can help in the absence of other learning support,” said public relations director Anne Chou (周家安) of Pegatron's design team.

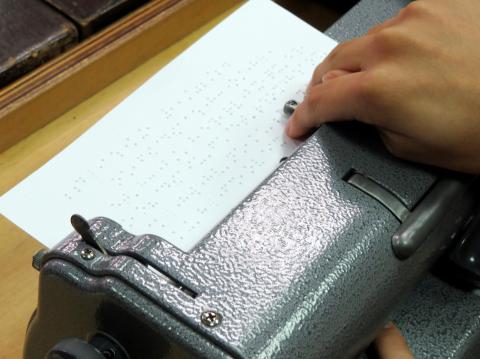

In Braille, every letter is represented by six dots that are either raised or not. In the version of Chinese Braille used in Taiwan, three raised dots in the 1, 3 and 5 positions represent bo, the first letter in the Zhuyin Fuhao (注音符號, commonly known as Bopomofo) phonetic system.

Photo: Enru Lin, Taipei Times

To master the system, children have to practice, normally relying on a wooden block with six holes for pegs. They place the pegs in a position and wait for a sighted instructor or parent to tell them if the letter is correct.

The simple beauty of the chip-fitted device is that it enables a blind child to practice Braille independently, because it pronounces any letter that the child punches in the interface. When the device is flipped over, the child can use it to practice reading, too.

The device, called Dotty, has won a Japan Good Design Award, a Red Star Design Award and this year’s Golden Pin Design Award.

Photo: Enru Lin, Taipei Times

“In reality, making a device like this is not so hard. Other companies have not done it simply because the market is too small,” Chou said.

“There aren’t that many six-year-olds to begin with, let alone low-income children who are visually impaired, and so for us this is something that we make in limited numbers for donation. This isn’t going to be a line of business.”

THE HUEI-MING CASE

Photo: Enru Lin, Taipei Times

In 2011, the first prototype was developed by a Pegatron team in Shanghai, and test trials have mainly taken place in China, where there is a significant population of disabled poor.

In Taiwan, the demographic exists too. Ten of Pegatron’s finished products are now being used at Huei-Ming School for Blind Children (惠明盲校), a private boarding school in Greater Taichung.

The school accepts students from low-income families only, mostly from rural Taiwan. Boarding and tuition are free and supported by government funding and private donations.

Photo: Enru Lin, Taipei Times

Conducted on second-grade students, the first trials were promising and resulted in stronger Braille recall in the classroom, said school principal Lai Hung-yi (賴弘毅).

“The fine thing about it is that it’s one single piece and you don’t lose small parts — the children used to drop the pegs and not be able to find them,” he said.

“So they could take this outside the classroom and use it regularly, the way sighted people use flashcards to learn English.”

Photo: Enru Lin, Taipei Times

Every Friday, buses pull up at the entrance and deliver most of the students home for the weekend. In the ideal situation, parents are able to support their Braille education at home, either by learning it themselves or hiring a tutor, and by incorporating the script into the child’s daily routine.

“But a lot of our students are here because the parents don’t know how how to help them and cannot pay for help,” Lai said.

Pegatron hopes the device can eventually be used by low-income blind children who have not yet entered the education system and who tend not to be taught Braille at home.

As with any language, higher levels of literacy are associated with exposure at a very young age, when the brain is most active in forming connections for language ability. Later on, high levels of Braille literacy correlate with high test scores and could — the school hopes — lead to better employment opportunities, although jobs for Taiwan’s blind remain limited in scope.

‘A DIFFERENT FUTURE’

At Huei-Ming, students who don’t have mental disabilities are taught the same curriculum as children in public schools. Though most of these students floundered in public school, they thrive here, partly due to the safe environment.

Max Chen (陳俊豪) is a lively 11-year-old who transferred in from a public school when he was eight. He said he is happy now, whereas he wasn’t before.

“In the other school, sometimes kids hit or pinched me or pushed me to the ground!” he said. “That was terrible.”

Another reason for the student success is easy access to assistive technology, which now includes the Dotty device. Others include Braille writers and computers fitted with refreshable Braille displays that allow students to complete homework, surf the Internet and read study guides that would have been inaccessible to them in a mainstream classroom.

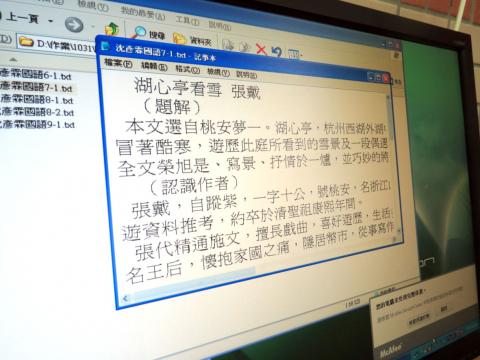

Shen Yen-lin (沈彥霖), a teen from Yunlin County, is seated at a computer and is impressively adept, toggling rapidly between windows. He pulls up a folder and its name shows up as Braille on the refreshable display. He picks a track titled Europa, a jazzy instrumental, and it starts to play.

“This is what I’ve been listening to these days,” he said.

“The kids here all have different tastes. Some like Christian songs, others like Taiwanese opera, some like pop. At my old school we didn’t have conversations about music because the other kids liked online role-playing games instead. You can’t play if you’re blind.”

Huei-Ming has an award-winning music program and some of its students do go on to become musicians. Others have gone into coding, customer service, food service, translation or administrative work.

Shen wants to become a computer programmer or a professional flautist.

“They say we should get a massage license anyway because it’s important to have a marketable skill, but I would not like to. Massage is boring. Every day you have to touch other people’s bodies, and you can easily get sued,” he said.

Chen Yuan-nan (陳淵楠), a blind alumnus who has taught computer skills at Huei-Ming for 20 years, said that massage remains a default career for a blind person, though options are improving.

“I would say that 20 years ago, over 95 percent of blind children went into massage work. Today, at least 30 percent are able to have a different future,” he said.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

When the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese forces 50 years ago this week, it prompted a mass exodus of some 2 million people — hundreds of thousands fleeing perilously on small boats across open water to escape the communist regime. Many ultimately settled in Southern California’s Orange County in an area now known as “Little Saigon,” not far from Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton, where the first refugees were airlifted upon reaching the US. The diaspora now also has significant populations in Virginia, Texas and Washington state, as well as in countries including France and Australia.

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with