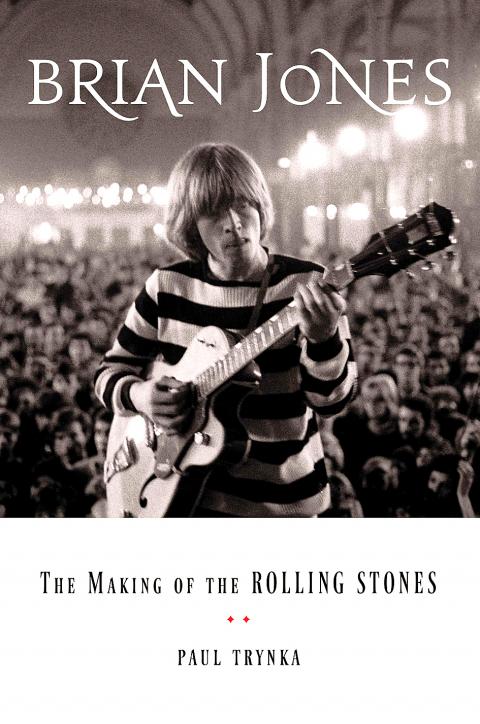

Brian Jones is to the Rolling Stones what Leon Trotsky was to the Russian Revolution: organizer, ideologist and victim of a power struggle. Jones founded the group, gave it its name and recruited the schoolboys Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, who then marginalized him, eventually expelling him from the band. Since his death in 1969, a month after he was forced out, Jones has largely been airbrushed from the group’s history.

Paul Trynka’s biography Brian Jones: The Making of the Rolling Stones challenges the standard version of events, focused on Jagger and Richards, in favor of something far more nuanced. Although Trynka sometimes overstates Jones’ long-term cultural impact, his is revisionist history of the best kind — scrupulously researched and cogently argued — and should be unfailingly interesting to any Stones fan.

Specifically, Brian Jones seems designed as a corrective to Life, Keith Richards’ 2010 memoir. Trynka, the author of biographies of David Bowie and Iggy Pop, and a former editor of the British music magazines Mojo and Guitar, has interviewed Richards several times over the years and obviously likes him, but also considers his memory of events highly unreliable.

“History is written by the victors, and in recent years we’ve seen the proprietors of the modern Rolling Stones describe their genesis, their discovery of the blues, without even mentioning their founder,” Trynka remarks in the introduction. Without naming Richards, he also expresses his distaste for an assessment that appears in Life, that Brian Jones was “a kind of rotting attachment.”

The portrait of Jones that Trynka offers here is bifurcated. Although he is impressed with Jones’ “disciplined, honed sense of musical direction” and his dexterity on guitar and many other instruments, he does not hesitate to point out his subject’s more unpleasant personality traits: He was narcissistic, manipulative, misogynistic, conniving and dishonest about money. It’s not accidental that this book is called Sympathy for the Devil in Britain.

Trynka attributes Jones’ downfall to a conjunction of factors, some related to those character flaws but others external to him. Much has been written about the drug busts that swept up Jagger and Richards in the mid-1960s and their court battles, although Jones seems to have been even more of a target, because he was such a dandy and so successful with women.

But as Trynka tells it, Jones did not receive strong legal advice or fight charges as hard or as successfully as the Jagger-Richards team. After his first arrest, he pleaded guilty, which drove a wedge between him and other band members, who feared it would mean they could no longer tour abroad, all of which left him feeling crushed, isolated and vulnerable. That, in turn, increased his consumption of drugs and alcohol and made him less productive as a musician.

Nevertheless, Trynka demonstrates convincingly that the original Rolling Stones were Jones’ band and reflected his look, tastes and interests, not just the blues but also renaissance music and what today would be called world music. (He recorded the master musicians of Joujouka in the mountains of Morocco.) In Life, Richards describes his discovery of the blues-tinged open G guitar tuning, familiar from hits like Honky Tonk Women and Start Me Up, as life changing, and says it came to him via Ry Cooder in the late 1960s. But Trynka notes that Jones often played in that tuning from the band’s earliest days and quotes Dick Taylor, an original member of the Stones, as saying, “Keith watched Brian play that tuning, and certainly knew all about it.”

Some of Trynka’s account is not new, having appeared in Stone Alone, the often overlooked 1990 memoir of the Rolling Stones bassist Bill Wyman, or other books written by band outsiders. What makes Trynka’s book fresh and interesting, and gives it credibility, is the length he has gone to find witnesses to corroborate and elaborate on those stories.

It’s not just that Trynka has sought out those who worked with the band on the creative side, such as the singer Marianne Faithfull, the arranger Jack Nitzsche and the recording engineers Eddie Kramer, Glyn Johns and George Chkiantz. He has also interviewed those with more of a worm’s-eye view: drivers, roadies, office staff, old girlfriends and former roommates like James Phelge, whose surname the band would appropriate to designate songs that were group compositions rather than Jagger-Richard numbers.

“Brian Jones was the main man in the Stones; Jagger got everything from him,” the drummer Ginger Baker, who played in the band at some of its earliest shows and went on to become famous as a member of Cream, says in the book. “Brian was much more of a musician than Jagger will ever be — although Jagger’s a great economist.”

In the end, with the advantage of 45 years’ perspective, Trynka maintains, it is Jones’ music that matters.

“It’s understandable why the survivors resent Brian Jones beyond the grave,” given his founder’s role, he argues, and also writes: “Brian Jones got many things wrong in his life, but the most important thing he got right.”

June 9 to June 15 A photo of two men riding trendy high-wheel Penny-Farthing bicycles past a Qing Dynasty gate aptly captures the essence of Taipei in 1897 — a newly colonized city on the cusp of great change. The Japanese began making significant modifications to the cityscape in 1899, tearing down Qing-era structures, widening boulevards and installing Western-style infrastructure and buildings. The photographer, Minosuke Imamura, only spent a year in Taiwan as a cartographer for the governor-general’s office, but he left behind a treasure trove of 130 images showing life at the onset of Japanese rule, spanning July 1897 to

In an interview posted online by United Daily News (UDN) on May 26, current Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) was asked about Taichung Mayor Lu Shiow-yen (盧秀燕) replacing him as party chair. Though not yet officially running, by the customs of Taiwan politics, Lu has been signalling she is both running for party chair and to be the party’s 2028 presidential candidate. She told an international media outlet that she was considering a run. She also gave a speech in Keelung on national priorities and foreign affairs. For details, see the May 23 edition of this column,

The Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on May 18 held a rally in Taichung to mark the anniversary of President William Lai’s (賴清德) inauguration on May 20. The title of the rally could be loosely translated to “May 18 recall fraudulent goods” (518退貨ㄌㄨㄚˋ!). Unlike in English, where the terms are the same, “recall” (退貨) in this context refers to product recalls due to damaged, defective or fraudulent merchandise, not the political recalls (罷免) currently dominating the headlines. I attended the rally to determine if the impression was correct that the TPP under party Chairman Huang Kuo-Chang (黃國昌) had little of a

At Computex 2025, Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang (黃仁勳) urged the government to subsidize AI. “All schools in Taiwan must integrate AI into their curricula,” he declared. A few months earlier, he said, “If I were a student today, I’d immediately start using tools like ChatGPT, Gemini Pro and Grok to learn, write and accelerate my thinking.” Huang sees the AI-bullet train leaving the station. And as one of its drivers, he’s worried about youth not getting on board — bad for their careers, and bad for his workforce. As a semiconductor supply-chain powerhouse and AI hub wannabe, Taiwan is seeing