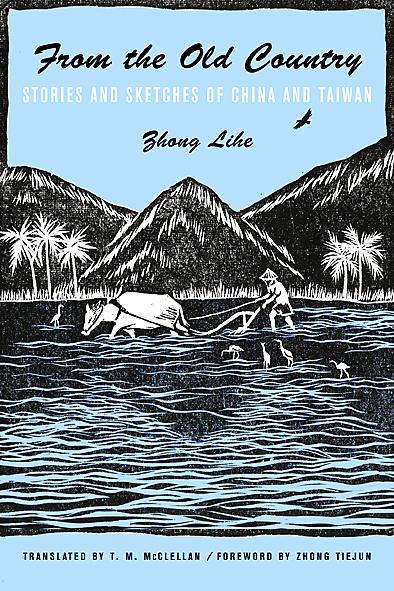

From the Old Country: Stories and Sketches of China and Taiwan is a new English-language anthology featuring Chung Li-ho (鍾理和, written as Zhong Lihe in the book), a Hakka from Pingtung County who experienced some of Taiwan’s greatest political changes.

Born in 1915, Chung lived his first 30 years as a citizen of the Japanese empire on Taiwan. In 1940, he ran away — to Japan-controlled Manchuria and then Beijing — so as to escape a taboo against same-surname weddings and marry his sweetheart Chung Tai-mei (鍾台妹).

Upon returning to Taiwan in 1946, they found it economically devastated by the Second Sino-Japanese War. In their new home in Meinong, Greater Kaohsiung, the Chungs seemed to experience every misfortune: drought, poverty, the illness of their oldest son, the death of their seven-year-old second son and Chung’s own tuberculosis that ultimately ended his life at 44. As his illness worsened, Chung threw himself into his work, writing mainly about the Hakka peasantry of southern Taiwan. Chung’s essays and short stories appeared in the Chinese-language United Daily News’ literary supplement, and his Lishan Farm (笠山農場) won the top national literary award for long fiction in 1956. Today, Chung is considered the founding father of Taiwan’s rural literature.

From the Old Country contains 16 stories translated by T. M. McClellan of the University of Edinburgh, who chose and ordered them chronologically into a fluid narrative. This collection dovetails with Chung’s biography, and each deepens understanding of the other. These stories are semi-autobiographical: The first-person narrator is often Chung himself, who others call “A-he.”

A-he’s world is laid out in calm and distilled statements, but it is filled with contradictions where ever he goes. In Forest Fire (山火), pious Taiwanese peasants are so desperate for the gods to spare them from forest fires that they set their own orchards on fire to preempt a strike. Meanwhile, A-he’s brother, ostensibly the voice of the gentry, looks on with disapproval yet is also pleased when he is able to contribute a special offering of waterfowl to the temple.

The Fourth Day (第四日), set in China, is about a demoralized contingent of Japanese soldiers four days after their emperor’s surrender. In a sudden brutal episode, a Japanese soldier attacks a Chinese cook and, as a result, draws upon himself the rage of another Japanese soldier.

Despite the destruction all around him on his travels, Chung does not accept the world as hostile and is indiscriminate in treating his subjects, be they Hakka, Korean, Japanese or Chinese, with an affectionate good nature. In Oleander (夾竹桃), completed in 1944, the Chinese tenants in a typical Beijing complex are selfish and prone to theft, but their circumstances of poverty are a persistent humanizing backdrop. Later in his short stories based in Meinong, Chung provides evenhanded sketches of people in decline. There is Bing-wen, a dullard and degenerate who used to talk with him about literature before the war. There’s “lazy” Uncle A-Huang, who lives in a squalid home and can’t be bothered to complete a construction job, but whose motivations and past glory are evoked slowly and carefully.

Some of Chung’s pieces are delicate miniatures, a few pages delivering a universal aphorism. In The Grassy Bank (草坡上), Chung describes how his family killed and ate an ailing hen. Driven by guilt, they redouble their efforts to tend to her chicks, and get an awe-filled and distinctly human satisfaction when the brood develops adult feathers.

Other stories are particular. “From the Old Country (原鄉人),” probably Chung’s most famous story, is about the identity crisis of a Hakka teenager who meets Japanese neighbors, a Hokkien person and some first-generation migrants from the “old country,” a Hakka term for China. My Grandma From the Mountains (假黎婆) is a candid recollection of his step-grandmother, a woman who helped raised him and was his inseparable childhood companion. As a young boy, he is astonished when she tells him she is an Aborigine and not Hakka like him. One day, she takes him high up on a mountain to look for a lost ox and she sings a song from the Paiwan tribe. “Bewitching as this singing grandma was, my inner feelings were of confusion and fear,” writes Chung, who agitatedly asks his grandmother to stop, and she does.

It’s a brief look at the vulnerable heart of Taiwan, where latent ethnic differences exist even in small enclosed communities and threaten to denature familial love. Chung’s stories, however, shelter a steadfast and prepossessing trust that the land will give birth to something that will carry the day in the end. In My Out-Law and the Hill Songs (親家與山歌), the protagonist peers over dried-up fields and notices young girls in headscarves singing a hill song, a local music tradition. “You could imagine those young, tender lives being nurtured and maturing in the bright sun,” he writes. “Amid all the change and upheaval, perhaps this was the only unchanging thing I could find.”

May 18 to May 24 Pastor Yang Hsu’s (楊煦) congregation was shocked upon seeing the land he chose to build his orphanage. It was surrounded by mountains on three sides, and the only way to access it was to cross a river by foot. The soil was poor due to runoff, and large rocks strewn across the plot prevented much from growing. In addition, there was no running water or electricity. But it was all Yang could afford. He and his Indigenous Atayal wife Lin Feng-ying (林鳳英) had already been caring for 24 orphans in their home, and they were in

On May 2, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), at a meeting in support of Taipei city councilors at party headquarters, compared President William Lai (賴清德) to Hitler. Chu claimed that unlike any other democracy worldwide in history, no other leader was rooting out opposing parties like Lai and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). That his statements are wildly inaccurate was not the point. It was a rallying cry, not a history lesson. This was intentional to provoke the international diplomatic community into a response, which was promptly provided. Both the German and Israeli offices issued statements on Facebook

Even by the standards of Ukraine’s International Legion, which comprises volunteers from over 55 countries, Han has an unusual backstory. Born in Taichung, he grew up in Costa Rica — then one of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies — where a relative worked for the embassy. After attending an American international high school in San Jose, Costa Rica’s capital, Han — who prefers to use only his given name for OPSEC (operations security) reasons — moved to the US in his teens. He attended Penn State University before returning to Taiwan to work in the semiconductor industry in Kaohsiung, where he

Australia’s ABC last week published a piece on the recall campaign. The article emphasized the divisions in Taiwanese society and blamed the recall for worsening them. It quotes a supporter of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) as saying “I’m 43 years old, born and raised here, and I’ve never seen the country this divided in my entire life.” Apparently, as an adult, she slept through the post-election violence in 2000 and 2004 by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), the veiled coup threats by the military when Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) became president, the 2006 Red Shirt protests against him ginned up by