When Claudio Abbado died on January 20, the entire classical music world went into instant mourning. Here was a conductor who was not only hugely admired but deeply loved. The Guardian critic said that a performance he’d heard in London of Abbado conducting Mahler’s Symphony No: 9 was the finest concert he’d ever attended.

Yet he wasn’t a charismatic authoritarian in the style of Herbert von Karajan or Arturo Toscanini. Universally perceived as quiet, attentive and introverted, he displayed the quality above all of reticence — something, someone commented, not often associated with Italians.

In fact Abbado was a man who, though born in Italy, made his name largely with music from north of the Alps. It was in conducting Mahler that he was supremely famous, and it’s significant that the Berlin Philharmonic, one of the two best orchestras in the world, and one that elects its principal conductor, chose Abbado to succeed Karajan following his death in 1989. In the years since 1955, the Berlin Philharmonic has only had three music directors — Karajan, Abbado and Simon Rattle.

So what, then, will be Claudio Abbado’s abiding recording legacy? It’s clearly impossible for any one critic to hear more than a fraction of what’s available, but combining the insights of others and my own favorites, this is a highly tentative evaluation.

Abbado put together the Lucerne Festival Orchestra, using hand-picked musicians, after he left Berlin. It was always likely that the symphonies of Mahler would loom large in their repertoire, and Abbado died with all except the massive Symphony No: 8 in the bag. His recording of the Symphony No: 1, combined with Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No: 3 with Yuja Wang as soloist, is heart-breakingly beautiful. Abbado was recording Mahler before his Lucerne days, of course, and his version of Symphony No: 6 is justly famous, and won Gramophone magazine’s Record of the Year award in 2006.

But for many fans Mahler’s Symphony No: 9 is the true summit of the composer’s achievement. “What is it about the 9th,” commented a friend of mine, “that connotes the valedictory? The last Mahler, conducted by Bruno Walter, before the Nazis marched into Austria, the last before Abbado’s passing?” It’s available, with the Lucerne forces, on an Accentus DVD.

An excellent idea for those wanting to get a measure of Abbado’s distinctive personality and musical style is to watch the 2003 film about him, Hearing the Silence. It’s available in the Naxos Video Library, though with no real subtitles other than the names of the works being played. Your German and Italian will need to be good to follow the rest.

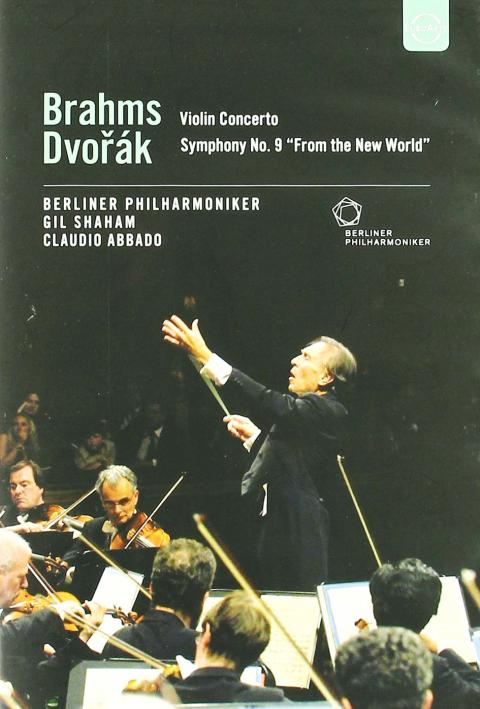

This film uses an Abbado performance of Dvorak’s New World Symphony to link its various sections. A DVD of that symphony as played in Palermo in 2002 by Abbado and the Berlin Philharmonic, together with Brahms’ Violin Concerto (soloist Gil Shaham) and two overtures, Beethoven’s “Egmont” and Verdi’s “Sicilian Vespers”, is available from EuroArts.

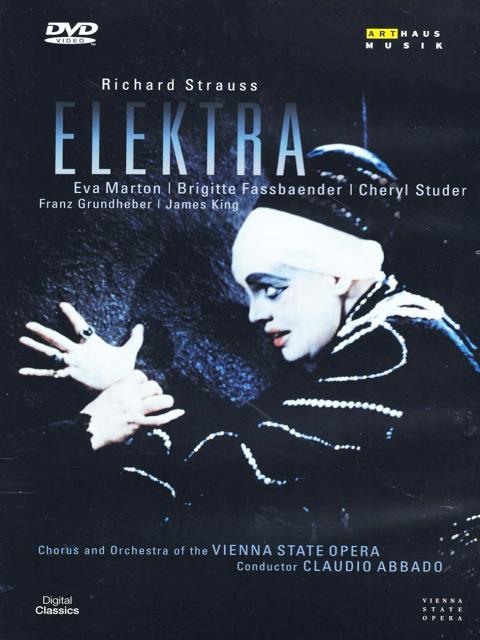

Abbado didn’t neglect opera, nor his fellow Italians. A clip in Hearing the Silence from Richard Strauss’s Elektra, featuring the meeting of Elektra and Orestes, is electrifying. His 1985 recording of Rossini’s Il Viaggio a Reims (The Journey to Rheims) at the Pesaro Festival is legendary (and on the whole marginally preferred to his later version for Sony). It had been carefully reconstructed, and was for modern audiences a new opera. And his version of Verdi’s Simon Boccanegra with Piero Cappuccilli and Mirella Freni is one of several striking recordings of Italian masterpieces from his years with La Scala, Milan (1968 to 1986).

Due out in the UK on Feb. 10 is a CD of Martha Argerich playing Mozart’s Piano Concertos Nos: 20 and 25 with Abbado and the Orchestra Mozart, a line-up Abbado also founded. Recorded at the Lucerne Festival in 2013, this will be, chronologically, the last of his recordings.

Among DVDs and CDs previously recommended in this column are the following: the two CDs of Schoenberg’s rarely-heard Gurrelieder with the Vienna Philharmonic [reviewed May 6, 2009]; the DVD of Mahler’s Symphony No: 1 and Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No: 3, with Yuja Wang (see above), both with the Lucerne Festival Orchestra [reviewed February 13, 2011]; the DVD of Abbado in Tokyo with the Berlin Philharmonic in 1994 playing Mussorgsky’s Night on the Bare Mountain, Stravinsky’s Firebird Suite and Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No: 5 [reviewed July 10, 2011]; the DVD in the Discovering Masterpieces of Classical Music series of Brahms’ Violin Concerto with the Berlin Philharmonic — with references, too, to Abbado’s stunning performance of Dvorak’s New World Symphony (see above), [reviewed January 10, 2012]; and the DVD of Abbado conducting the Simon Bolivar Youth Orchestra of Venezuela in Prokofiev’s Scythian Suite, Berg’s Lulu Suite and Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No: 6 [reviewed July 10, 2012].

In 1732 Samuel Johnson (“Dr. Johnson”) wrote an epitaph on another musician called Claude, his friend Claudy Phillips. Johnson was a believer, as well as a poet and much more, but one doesn’t need to share his faith to think of his eloquent closing words when bidding farewell to Claudio Abbado, one of the greatest conductors of any era.

Sleep, undisturbed, within this peaceful shrine,

Till angels wake thee with a note like thine!

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,